Abstract

Cunha’s Supervisor’s General and Specific Competencies Scale (

Keywords: Factorial structurecompetenciesteacherssupervision

Introduction

Higher education students are those who are regularly enrolled in an institution of higher education recognized by the formal education system currently followed in their country, Portugal. In addition to the students’ formal status, these students exhibit a range of specific characteristics: a distinct personality, the ability to adapt to different environments, a capacity that will influence their academic performance, their soft skills and their psychosocial development.

When they enter higher education, students are exposed to several changes that will make them experience things differently. These changes may, on the one hand, contribute to their development, independence and autonomy processes and, on the other hand, become a source of inadequate and/or disturbing sensations. As such, students’ adjustment to higher education is complex and can generate stressful situations throughout their academic life. During this process of transition that will affect the students’ lives, the mentor teachers will play a crucial role since the will contribute to mitigate the impact of the new demands that are part of this new reality and to ensure the normal development of these students’ academic life (Cunha et al, 2017).

The mentoring process is dynamic, reciprocal and reflective, so all the competencies that may enable people to act in a pertinent way when dealing with a specific situation (Le Boterf, 2003) have to be monitored during the mentorship. If we want a student to achieve success, teachers will have to play different roles: they will have to be mentors, advisors and supervisors. The supervisor will also be responsible for the whole negotiation process that will involve the supervision strategies and the supervised student, always taking into account the students’ personalities, their acquired knowledge and the goals they had previously set for themselves. That kind of commitment will help establish a relationship that will favour the students’ learning. The pedagogical supervision aims to ensure a learning process that should be developed in accordance with the biopsychosocial context of higher education students.

The supervisors’ pedagogical qualities and capacities need to be improved during their educational path and this improvement will have to focus on all the different learning situations. (Gaspar, Jesus & Cruz, 2011). In addition to the implementation of a mentoring practice supported by different technical and behavioural components, the supervisors’ needs to be able to assume a self-reflection attitude and to have highly developed observation skills so they are be able to lead students to new and relevant knowledge.

Banha & Ciência (2017), citing a recent review of the literature dealing with the ideal characteristics that mentor teachers should possess, claims that they should be able to:

provide a suitable environment for an independent, impartial and confidential discussion ...that will help solve the problems presented by the students ...; mediate for understanding between the concerned parties and find clues to solve the problems; assess the complaints addressed by the students and issue recommendations that will have to be followed by the concerned parties and that will lead to the suspension, change or transformation of those acts that negatively affect the students’ rights, recommendations that will also lead to an improvement of the services provided; help clarify policies and procedures … that will be carried out in the pedagogical field and will have an effect on the school social action programme and … recommend the necessary and suitable changes; issue opinions on any matter in its sphere of action ...contribute to the preparation and updating of the students ' disciplinary regulation and of the students’ code of conduct. (p. 30)

The supervisor as mentor should possess several competencies and duties, among other characteristics, that will enable him to meet the mentored student’s needs. Mentors must truly believe that their knowledge and experience are more than appropriate, they must constantly strive to develop and strengthen these competences, attending relevant training courses, in order to properly develop their professional skills. They should also be able to maintain a close relationship with a qualified supervisor to periodically assess their aptitudes and find the support they needs to back up their own development (Karkowska, et al 2015).

In order for this relationship to be pedagogically fruitful and provide educational gains, mentors must have supervisory competencies that will enable them to transform the didactics of the teaching and learning process into academic accomplishments that will subsequently be transferred to the teaching/work contexts (Cunha, 2017).

Supervision is closely related to safety and to productive professional relationships since it is an effective way to explore issues related to professional practice, allowing teachers not only to learn from one another, to offer support to one another, to understand how they are perceived and valued by their peers, but also to control the concern and the anxiety caused by the tasks and functions that are part of their professional activity (Jones, 2003, as cited in Cruz, 2012).

The supervisors’ role should include three predominant requirements that will influence their actions and personal style of operation: the knowledge, interpersonal skills and technical competencies. Glickman (1985, as cited in Alarcão & Tavares, 2007) identifies three supervisory styles: the non-directive, the collaborative and the directive. A non-directive supervisor praises the supervisees’ perspectives and opinions, knows how to encourage them and help them clarify their ideas and feelings. Collaborative supervisors prioritise the communicational component that exists between them and their supervisees, guiding them and helping them solve the problems they will have to face. Supervisors of the directive type are more concerned with the discipline and the guidance provided to their supervisees, establishing criteria and controlling their attitudes.

Supervisors will also be responsible for negotiating the supervision strategies with their supervisees, taking into account their personality, their acquired knowledge and the goals that have been previously set in order to establish a kind of relationship that will favour the teaching and learning process.

This study aims to assess the CGES scale psychometric qualities, in order to assess the mentor teacher’s competencies according to the higher education students’ perspective.

Problem Statement

Cunha’s Supervisor’s General and Specific Competencies Scale (Cunha, 2017) was designed to assess the mentor teachers’ ideal competencies according to higher education students’ perspective. The development of further educational/pedagogical research in this area is essential to update the existing knowledge.

Research Question

What is the psychometric quality of Supervisor's General and Specific Competencies Scale (2017)?

Purpose of the Study

This study aims to assess the psychometric properties, the factorial structure and the internal consistency of Cunha’s (2017) Supervisor’s General and Specific Competencies Scale.

Research Methods

The methodological study is part of the project “Supervisão e Mentorado no Ensino Superior: Dinâmicas de Sucesso (SuperES)” Ref. PROJ/CI&DETS/CGD/0005 (supervision and mentoring in higher education: Successful Dynamics) which was approved (No. 3/2017) by the Escola Superior de Saúde de Viseu (School of Public health of Viseu) Ethics Committee, a branch of the Polytechnic Institute of Viseu, in Portugal.

This cross-sectional study aims to assess the psychometric qualities of the Supervisor’s General and Specific Competencies Scale (CGES) to help assess the mentor teacher’s competencies according to higher education students’ perspectives.

Participants

The non-probability sampling for convenience was formed by 306 higher education students attending a health-related course. The majority of the participants were female (81.7%). The youngest participants were 18 and the eldest were 42 and the average age was 21.15 years (± 3.54 SD). Male participants were on average older (Mean = 22.28 years ± 4.21 SD) than female participants (Mean ± 3.32 SD) with statistically significant differences (z =-3,058; p = 0.002).

Data collection Tools

The collection of information was carried out through the questionnaires protocol available online that includes:

“Sociodemographic Characterization and Pedagogical Context” scale (Cunha, 2017),

The “Supervisor’s General and Specific Competencies Scale (CGES)” (Cunha, et al, 2017)

(Cunha, Cruz, Menezes & Albuquerque, 2017) which aims to help assess the mentor teacher’s competencies according to higher education students’ perspectives.

The Supervisory General and Specific Competencies Scale (CGES) included, in its original version, 24 items and was developed for higher education students. Its main objectives are to assess the students ' perspectives about the mentor teacher’s competencies. It features three subscales that include 24 items created specifically for this purpose:

-"Generic competencies" consisting of 14 items (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14);

-“Specific competencies" which includes 6 items (15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20);

-"Metacompetencies" which includes 4 items (21, 22, 23, 24).

We used a Likert-type scale and the responses given to the items were rated from 1 to 5: 1 – "Strongly disagree"; 2-"Disagree"; 3 – "Neither agree nor disagree"; 4 – " Agree" and 5 – "Strongly agree”.

The Fundamentals of the Psychometric study

The "Supervisor’s Core Competencies" Scale was built from theoretical constructs. Therefore, we chose to carry out tests of reliability and validity.

These two constructs are two related measurement properties that play complementary roles. In fact, while reliability relates to the consistency or to the stability of a measure, validity is related to its veracity.

Reliability means that the measurement method is accurate and that it can be verified through the analysis of the internal consistency or of the homogeneity of the items and of their temporal stability. A measurement instrument is said to be reliable if it does not produce significantly different results when administered at different times to the same individuals.

A test or a measurement instrument is said to be valid if it can correctly translate what it intends to measure. With this assumption in mind it becomes clear that reliability does not imply validity but is a requirement to assess validity which means that to be valid, a measure should first of all be reliable (Marôco, 2014).

The reliability studies are obtained with the determination of a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and of the Split-half reliability coefficient. This last method allows proving whether one of the halves of the items from the scale is as consistent as the other half to measure the construct. The values of the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient can fluctuate between 0 and 1. The higher the coefficient, the better. To achieve a good internal consistency, the Cronbach’s alpha must be above 0.80 (Marôco, 2014). The literature reviewed identifies the following reference values: above 0.9 (very good); 0.80-0.90 (good); 0.70-0.80 (average), 0.60-0.70 (reasonable), 0. 50-0.60 (mediocre) and below 0.50 (unacceptable).

For the study of this scale, we tested not only its internal consistency, but also the tri-factorial solution that emerged from the theoretical constructs, through an confirmatory factorial analysis (CFA), using the AMOS 24 Software (Analysis of Moment Structures). This statistical procedure is used to confirm whether or not the hypothesized factorial structure is adjusted for the data sample we intend to study.

We took into account, in the development of the CFA, the covariance matrix and the MLE (Maximum Likelihood Estimation) algorithm, a method used to estimate the parameters of a statistical model.

Then, we followed Marôco’s (2014) assumptions in particular:

-The study and assessment of the normality of the items: using the asymmetry coefficient (Sk) and the kurtosis coefficient (k) and the multivariate coefficient of variation whose reference values are respectively < = 3.0, < = 7.0 and 5.0.

-The quality of the local adjustment of the model through the calculation of the lambda coefficients (λ) that will determine the factorial weights of the items and the determination of the individual reliability of the items (δ) with reference values of 0.50 and 0.25, respectively.

-Quality indicators of the global adjustment of the model: (a) ratio between the chi-square and the degree of freedom (x ²/GL), with appropriate values below or equal 5; (b) the root mean square residual (RMR) and Standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) have to be as low as possible, given that the adjustment is perfect when they equal 0; as for the Goodness Fit Index (GFI) and Comparative Fit Index (CFI) the recommended values should be above 0.90 to reflect a good adjustment; the Root mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) shows the existence of a good adjustment when it is between 0.05 and 0.08 and very good when the index value is below 0.05.

Composite Reliability (CR) was used to study of the internal consistency of the items included in each factor. This measure is quite similar to Cronbach’s alpha and points to values above 0.70;

-Convergent validity was used to determine whether or not the items that reflect a certain factor are strongly saturated in that factor. Values above 0.50 are suggested;

-Discriminant validity was assessed through the comparison between the convergent validity for each factor and the Pearson coefficient of determination (R-squared) between factors. We assume that discriminant validity exists when the convergent validity for each factor is higher than the R-squared between factors.

Findings

With regard to the Supervisor’s General and Specific Competencies Scale (CGES) original 24-item version, the statistics (mean and standard deviations) and the correlations obtained between each item and the global value described in table

Correlative Indexes show that all items present values above 0.40 and through Cronbach’s alpha coefficient they were considered “very good” , ranging from α = 0.971 in Items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19, 20 to α = 0.976 in Item 24 "Provides feedback without being critical". Cronbach’s alpha values, for the global value, showed a very good internal consistency (α = 0.973).

All the items presented correlations with the global factor above 0.20, so we submitted the 24 items to a confirmatory factorial analysis using for this purpose a varimax orthogonal rotation method and the scree plot test to determinate the factors with values above 1 that should be retained.

The KMO test revealed a 0958 value and Bartlett's test for sphericity showed significant differences (x2 = 7605. 547; p = 0.000). These results suggest that we can continue with the validation process. The common factor variances are above 0.40, ranging from 0626 in item 24 to 0832 in item 18.

We could extract three factors which together account for 73.71% of the total variance and present values above 1.

The first factor/subscale entitled "Generic competencies", accounts for 63.84% of the total variance and contained fourteen (14) items (1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13,14 and 15);

The second factor/subscale entitled "Specific competencies", explains 5.02% of the total variance and includes six (6) Items (2, 16, 17, 18, 19 and 20);

The third factor/subscale named "Metacompetencies", explains 4.84% of the total variance and integrates four (4) Items (21, 22, 23 and 24).

The trifactorial structure was then subjected to a confirmatory factor analysis. Table

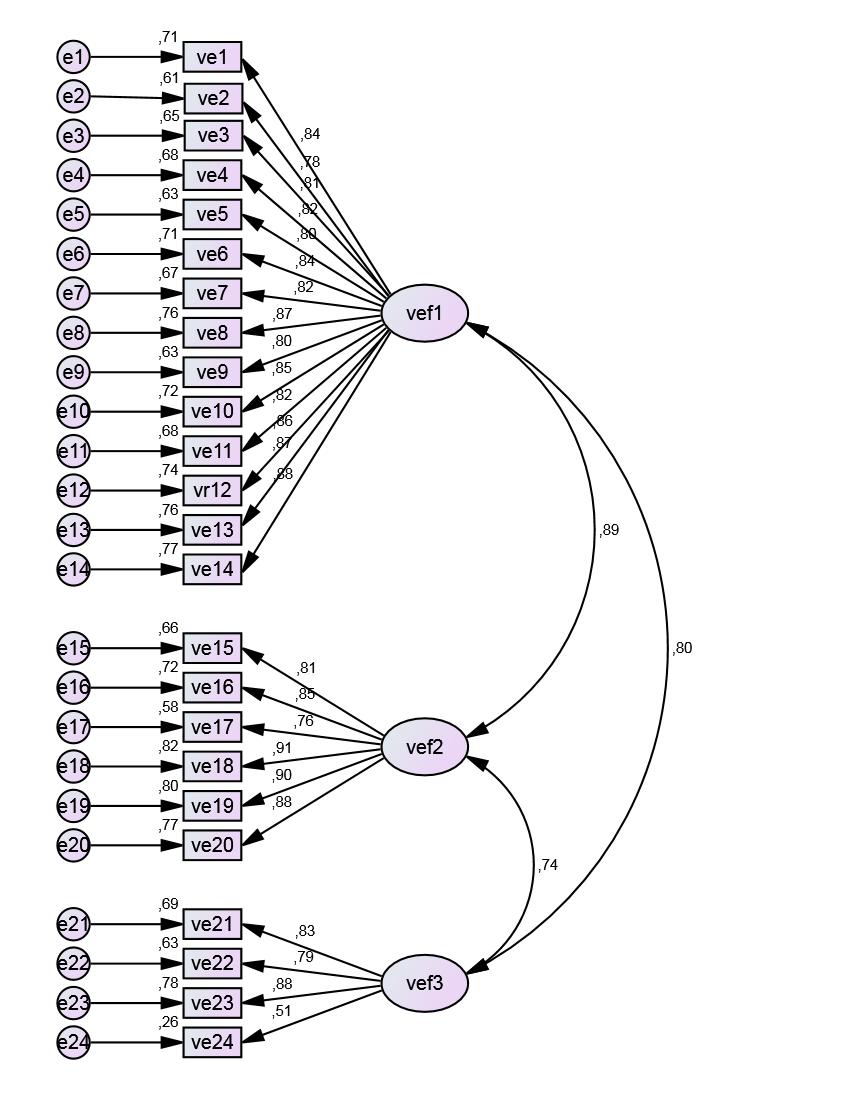

The trifactorial hypothesized model is considered in Figure

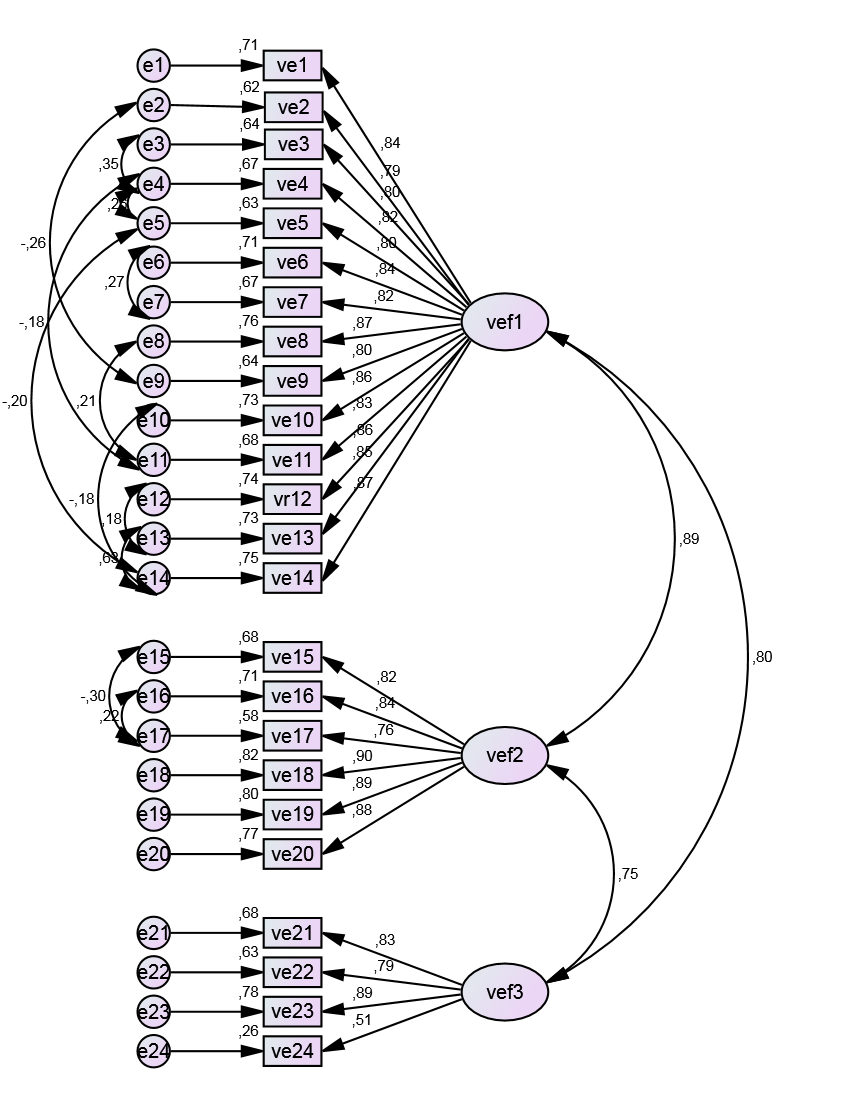

The model was refined using the modification indices made available by AMOS. The results derived from that process are expressed in Figure

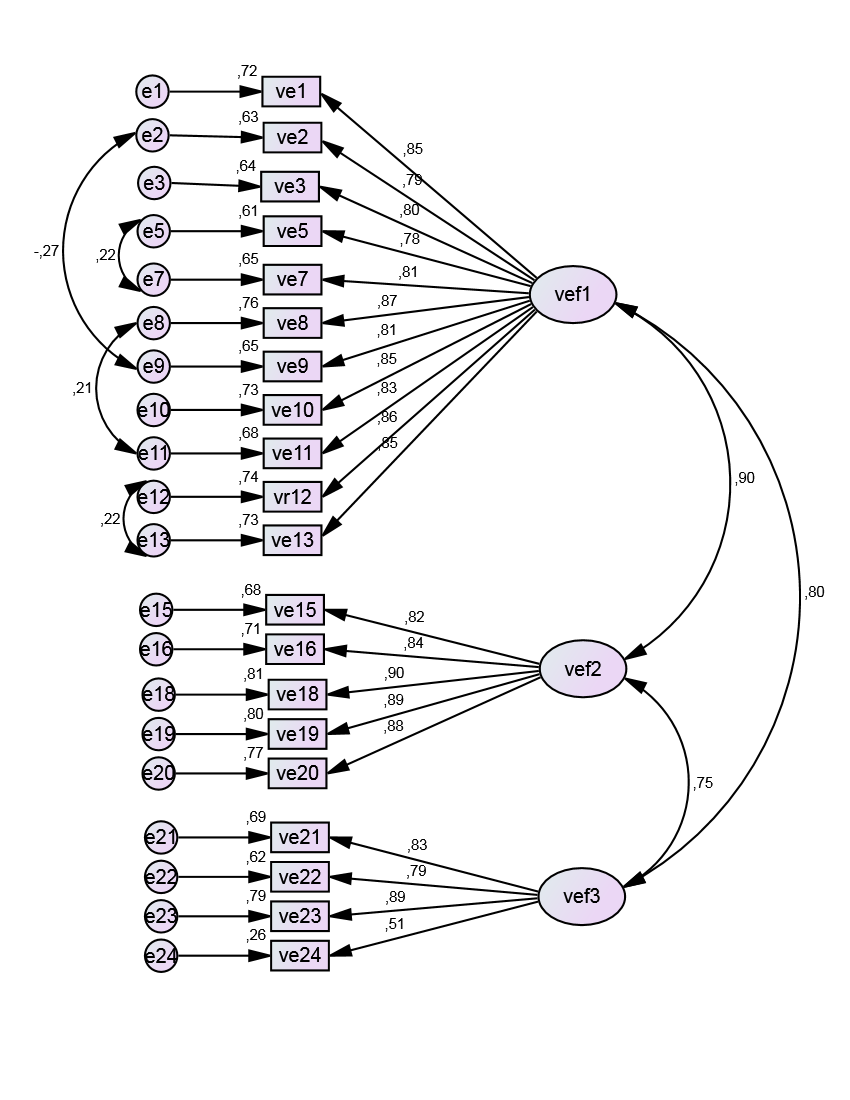

Once these items were eliminated, the modification indices suggest that item 6 from factor 1 should also be eliminated since it shows signs of multicollinearity problems. Figure

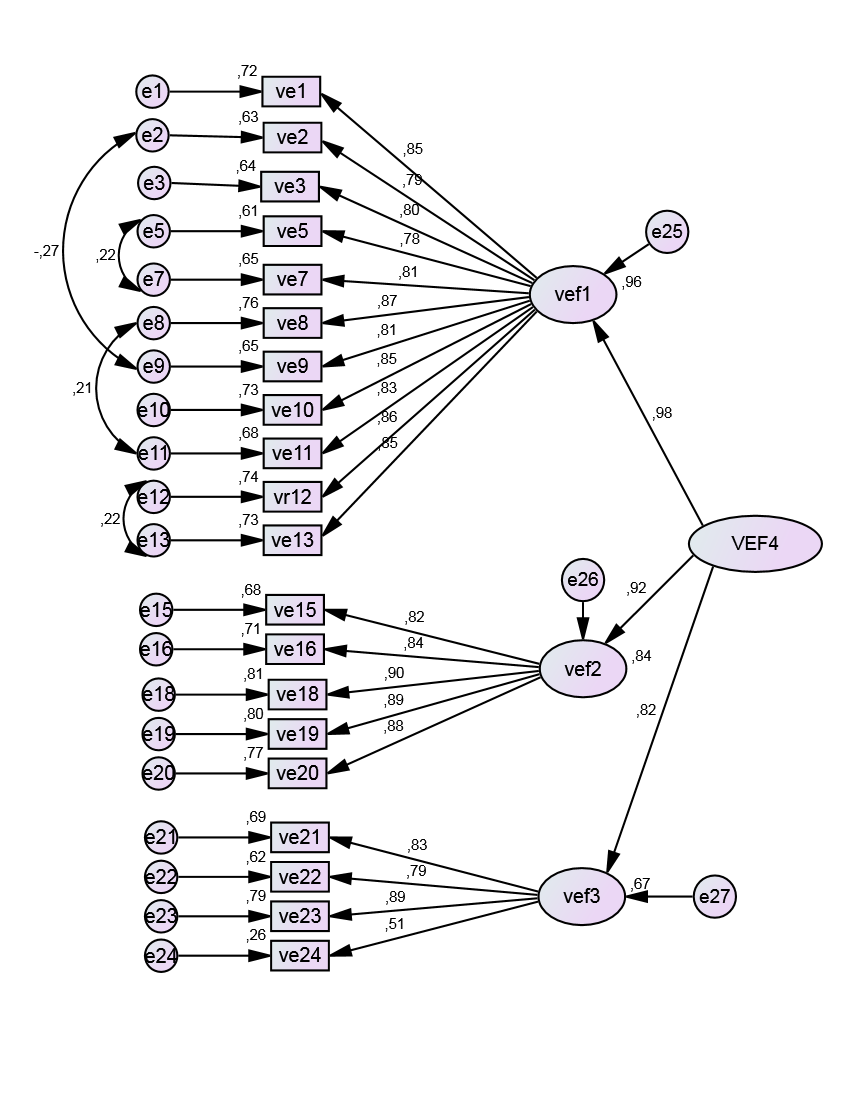

Since the correlative values suggest a second order model, a hierarchical structure with a second order factor entitled "Mentoring Teachers Competencies" (VEF4) was suggested. This structure is shown in Figure

The global adjusted goodness of fit indices are presented in table

The confirmatory factorial analysis is concluded with the results obtained from the CR, AVE and from the Discriminant Validity. It is a fact that all factors exhibit good consistency and good convergent validity indexes since they are all above reference values. Discriminant validity is evident between all factors but between factor 1 and factor 2 (table

The stratified composite reliability (0.977) and the convergent validity (0.682) for all scales are adequate.

Supervisor’s General and Specific Competencies Scale (CGES) Internal Consistency

The study of the Supervisor’s General and Specific Competencies Scale (CGES) internal consistency revealed, as it has already been mentioned, the existence of three (3) factors/subscales. With the application of the psychometric study (table

As for the "specific competencies" subscale the most favourable item is item 15 "Helps the supervisees acquire and develop specific professional skills (achieving theoretical/practical interconnection)" and the least favourable is item 18 "Develops pedagogical supervision processes for specific contexts/models”; however, the results indicate that the average values and the respective standard deviations obtained are well-centred. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the 5 items included in this dimension and that range between (α = 0.915) in item 18 "Develops pedagogical supervision processes for specific contexts/models” and (α = 0.934) in item 15 " Helps the supervisees acquire and develop specific professional skills (achieving theoretical/practical interconnection)" reveal a very good internal consistency with a total alpha of α = 0.937.

The highest correlation value is found in item 19 (r = 0.853) and the item that has the lowest correlation is item 15 (r = 0.769) with a variability of 74.9% and 59.6%, respectively. Cronbach’s alpha for the global Specific Competencies subscale was 0937.

As far as the "Metacompetencies" subscale was concerned, the best mean value is found in items 22 and 23 “Is eager to learn” and “Has a captivating and supporting attitude towards his supervisees” with a 4.52 mean value and the lowest mean value was witnessed for item 24 "Provides feedback without harsh criticism " with a 4.24 value. The Cronbach’ alpha coefficients in this dimension range between (α = 0.710) in item 23 "Has a captivating and supporting attitude towards his supervisees " and (α = 0.870) in item 24 "Provides feedback without harsh criticism" with a (α = 0.805) global Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. These values suggest that there is a good internal consistency. The highest correlative value obtained is found in item 23 (r = 0.743) with a variability of 66.1% and the lowest value is found for item 24 (r = 0.486) with a variability of 32.7%. The Cronbach’s alpha for the global Metacompetencies subscale was 0805.

Globally, the CGES 20-item scale defined by Cunha, Cruz, Menezes & Albuquerque (2017) obtained a 0.967 Cronbach’s alpha value and the items were grouped within the three subscales as follows:

-"Generic Competencies": 11 items (1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13);

-"Specific Competencies": 5 items (15, 16, 18, 19, 20);

-"Metacompetencies": 4 items (21, 22, 23, 24).

The convergent/divergent validity between the items and the corresponding dimensions is shown in table

To conclude the psychometric study, we present the Pearson’s correlation matrix between the three competencies and the global value of the Supervisor's Generic and Specific Competence Scale. The assessment carried out shows that the coefficients obtained are positive and statistically significant, ranging between 0.660 in the metacompetencies, which explains a strong positive correlation, and 0.972 in the specific competencies, thus proving a very strong correlation. According to the global factor, correlations are higher when they obtain percentages of explained variance above 35% (table

Supervisor’s General and Specific Competencies Scale (CGES) final 20-item version versus gender and age

The statistical analysis of the scores obtained for the Supervisor’s General and Specific Competencies Scale (CGES) global value (Cunha, Cruz, Menezes & Albuquerque, 2017) reveals that, taking into account the total sample, there was a general fluctuation between a minimum of 2.20 for “Disagree '” and a maximum of 5 for “Strongly agree “, with an average of 4.41 (± 0.45 sd).

In the generic competencies subscale, the values varied between a minimum of 2 and a maximum of 5, obtaining a 4.44 (± 0.47 sd) average score. The specific competencies subscale provided responses ranging between a minimum of 2 and a maximum of 5, with a 4.36 (± 0.52 sd) mean value. For the metacompetences subscale, the values varied between a minimum of 2 and a maximum of 5, with a 4.42 (± 0.49 sd) mean value.

The analysis of the scores concerning the Supervisor’s General and Specific Competencies Scale (CGES) for both genders was carried out through the Mann-Whitney U test. It was found that on the whole and for the different factors/subscales, the mean values were lower when the respondent was a male. However, there were no statistical differences, so we can conclude that there is equivalence between the values found for both genders (p > 0.05).

A variance analysis was carried out to evaluate the scores variability of the supervisor's generic and specific competencies according to the higher education students’ age group. It was found that students under the age of 19 preferred the supervisor's generic skills, while metacompetencies are preferred by students aged between 20 and 21 years and by those who are over 22. Young people aged between 20 and 21 got lower scores than the older ones in all subscales and in the global scale, as well. The values of F are explanatory and show that there are statistically significant differences when different age groups are involved. This happens for all subscales, except for the metacompetencies subscale (p = 0.120). We applied Turkey’s post-hoc test and it proved that these differences are evident among those who are under 19 and between 20 and 21 and in the responses they gave to the CGES generic and specific competencies subscales and in the global scale. For the generic competencies subscale, there are still significant differences between the younger students (≤ 19) and the older ones (≥ 22). For the remaining subscales, statistically significant differences were not observed.

Conclusion

The study of the psychometric qualities of the 20-item Supervisory General and Specific Competencies Scale (CGES) (Cunha, et al, 2017) shows that the values of internal consistency in the three subscales and in the global score are robust. However, some limitations for the psychometric analysis were detected: the size of the sampling with 306 participants and the fact that the participants’ age was quite low (Mean age = 21.15 years). Those components may have influenced the results. It is essential that future studies analyse the relationship between the variables currently studied, so that these results may be compared to those obtained using other samples of the Portuguese population.

Social desirability was not a controlled factor and this may have influenced the answers obtained, since the scale included moments in which the participants would have to favour auto-responses. It would also be interesting to replicate this factorial study using broader, foreign and more balanced samples in terms of age and students’ academic choices in which the social desirability variable would be controlled.

The discussion of the empirical results obtained from studies already published shows that students value all of the supervisors’ competencies- generic, specific and their metacompetencies. These results concur with the assumptions presented in Glickman’s supervisory styles (1985) cited by Alarcão and Tavares (2007), when he states that competencies should be a pillar that supervision action should value and that the role of the supervisor must contemplate three predominant requirements that will determine the action and the style of the supervisor's performance: knowledge, interpersonal skills and technical skills.

The results of this study support the importance of assigning a supervisor in higher education. This conclusion is also expressed in the study conducted by Botti & Rego (2007) that mentions the important role played by the supervisor on a personal and professional level.

This research constitutes the first evaluation of the psychometric quality the Supervisor’s General and Specific Competencies Scale measurement properties (Cunha et al, 2017), using a sample from the Portuguese population. The study shows that the internal consistency values in the different subscales and in the global score are strong, because the evaluation of the psychometric properties, namely the factorial structure and the internal consistency of the scale (CGES) obtained high alpha values.

The CGES scale revealed the existence of three (3) factors/subscales: 1 – Generic Competencies (α = 0.960); 2 – Specific Competencies (α = 0.937) and 3 - Metacompetencies (α = 0.805). The Cronbach’s alpha value for the global 20-item scale was 0.967. The empirical results stress that students under 19 value their supervisor's generic skills, while metacompetencies are preferred by older students, and the difference scores are statistically significant. The results clearly suggest that the generic and specific competencies and the metacompetencies evidenced by the supervisor should be considered in the assessment of his performance as a supervisor.

As a contribution to the pedagogical practice carried out in higher education, the results show that it is of paramount importance that we identify the impact of the supervisor on the students’ failure/school dropout. This knowledge is crucial since it provides the right setting to build educational contexts where innovation will play an important role and where we will develop academic strategies and practice that will foster a more personal and student-focused pedagogical relationship. All this could be an important contribution to the promotion of academic success, a goal whose relevance is even greater given the demands of current didactics.

Acknowledgments

FCT, Portugal, CI&DETS, Escola Superior de Saúde, Instituto Politécnico de Viseu, Portugal and Caixa Geral de Depósitos and CIEC, Minho University, Portugal.

This investigation was previously funded by the FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology) within the project

We would like to express our gratitude to all the participants that made this study possible and to the students of the 30th CLE of the ESSV – IPV - Ana Marques, Ana Gomes, Daniela Nascimento, Joaquim Pereira, Joel Lopes, Marta Murtinheira, Raquel Rosa & Sérgio Gonçalves

References

- Alarcão, I., Tavares, J. (2007). Supervisão da prática pedagógica: uma perspectiva de desenvolvimento e aprendizagem. 2ª edição, Coimbra: Almedina.

- Banha, R., (EEEC), Ciência, E. d., & (DGEEC), D. G. (2017). Promoção do Sucesso Escolar nas Instituições Públicas de Ensino Superior em Portugal: Medidas Observadas nos Respetivos Sítios. (D. d. Ciência, Ed.) Lisboa.

- Botti, S., & Rego, S. (2007). Preceptor, Supervisor, Tutor e Mentor: Quais são os seus paspéis? Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica, 32, 363-372.

- Cruz, S. S. (2012). Do AD HOC a um Modelo de Supervisão Clínica em Enfermagem em Uso. Tese de Doutorado, Universidade Católica Portuguesa do Porto, Instituto de Ciências da Saúde, Porto.

- Cunha, M. (Inv.Resp.) (2017). Projeto Supervisão e Mentorado no Ensino Superior: Dinâmicas de Sucesso (SuperES) (REFª: PROJ/CI&DETS/CGD/0005). Obtido de http://www.ipv.pt/ci/projci/5.htm

- Cunha, M., Duarte, J., Sandré, S., Sequeira, C., Castro-Molina, F.J., Mota, M., Pina, F., Coelho, C., Cunha, A., Figueiredo, A., Martins, A., Correia, B., Monteiro, D., Moreira., F. Silva, M., & Freitas, S. (2017). Bem-estar em estudantes do ensino superior Millenium, 2(ed espec nº2), 21-38.

- Gaspar, D., Jesus, S. N., & Cruz, J. P. (2011). Motivação Profissinal e Apoio Fornecido no Estágio. Acta Médica Portuguesa, 24, 137-146.

- Karkowska, M., Cieplik, C., Krukowska,K., Tsaroucha, V., Dimos, I., Papagiannopoulou, P., Leire Monterrubio, Iratxe Ruiz, Jaione Santos, Duse, C., Duse, D., Chisiu, C., Gruber, G., Andron,D., Crețu, D., Ventura,M., Mendonça, M. (2015). MENTOR - Mentoring between teachers in secondary and high schools. / O método modelo de mentoria entre professores no ensino secundário e superior - 2014-1-PL01-KA200-003335. Polónia, Grécia, Portugal, Roménia, Espanha, Turquia. Lisboa: Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, Portugal. Retrieved from http:// edu-mentoring.eu; http://edu-mentoring.eu/handbook/handbook_pt.pdf

- Le Boterf, G. (2003). Desenvolvendo a competência dos profissionais. Porto Alegre: Artmed

- Marôco, J. (2014). Análise Estatística com utilização do SPSS (3ª ed.). Lisboa: Edições Sílabo.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

29 October 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-046-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

47

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-75

Subjects

Psychology, clinical psychology, psychotherapy, abnormal psychology

Cite this article as:

Cunha, M., Albuquerque, C., & Cruz, C. (2018). The Factorial Structure Of The Supervisor’s Generic And Specific Competencies Scale. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, R. X. Thambusamy, & C. Albuquerque (Eds.), Clinical and Counselling Psychology - CPSYC 2018, vol 47. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 28-45). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.10.3