Abstract

There are shortcomings in judicial review and appeals of dismissal matters mainly on the Minister’s discretionary powers in the referral stage, and also the finality of the Industrial Court’s decision. Firstly, the discussion focuses on the Ministerial Discretion given by Section 20(3) of the Industrial Relations Act 1967 (“IRA”). The “moneyed-employer” files judicial review against the Minister’s decision at the referral stage might causes the jobless employees who are poor engaging in an unequal legal battle against the employer. Regardless of finality clause (Section 33B IRA), the aggrieved party files judicial review under Order 53 Rules of Court 2012 against the Industrial Court’s decision on the ground of error of law. Judicial review affects the access to justice by the poor workmen, when they cannot afford highly escalated legal fees. Appellate processes under Order 53 Rule 9 Rules of Court 2012 against High Court’s decision is opened to abuse when the poor workmen forced to expend exorbitant costs for the prolong legal battle. Additional time and costs incurred caused halts the determination to seek for justice. Judicial review and appeals of dismissal disputes are opened to abuse causes poor workmen expended exorbitant costs and faces prolong litigation. Section 33B of IRA stipulates the Industrial Court’s award shall be final. Practically, the civil courts circumvent the ouster clause by looking on regularities of the decision-making process. Minister’s discretion seems handy to avoid flooding of frivolous cases, but justification of the exercise of such discretion leads to predicaments.

Keywords: LabourLawIndustrialAppealReformMalaysia

Introduction

Employment dismissal disputes may arise when employees are dismissed by employers. The employment dismissal disputes between the employers and employees are governed by the Industrial Relations Act 1967 (hereinafter referred to as the ‘IRA’). Section

“trade dispute” means as any dispute between an employer and his workmen which is connected with the employment or non-employment or the terms of employment or the conditions of work of any such workmen.”

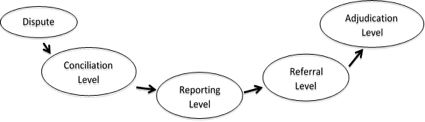

When a dismissed employee considers himself to have been dismissed without just cause, he may make representations in writing to the Director General for Industrial Relations (hereinafter referred to as ‘DGIR’) to pray for reinstatement in his previous employment. Such representation shall not be made after sixty (60) days of the dismissal. It is DGIR’s duty to consider the dispute and take necessary steps to promote a prompt settlement. The vital steps to be carried out by the Director General in his role as conciliator of trade disputes are stipulated in Section 18 of IRA 1967. A two-sided negotiation between the employer and the employees will usually take place once the DGIR receives the representation from the dismissed employee. If there is no likelihood in reaching a settlement in any direct negotiations between the parties in dispute, either party could report to the DGIR and the DGIR shall notify the Minister of Human Resources if the DGIR is satisfied that the parties in the dispute cannot settle.

Upon such notification by the DGIR, by virtue of Section 20(3) of the IRA, the Minister is then conferred with discretion on whether or not to refer the dispute to the Industrial Court for adjudication. This is known as the “referral level”. After the Minister has perused and inspected the facts and circumstances regarding the dismissal and is satisfied that the representation is not frivolous or vexatious, the Minister may refer the case to the Industrial Court to be adjudicated. Once the Minister refers the matter to the Industrial Court, the Industrial Court will act as an adjudicatory tribunal. Unlike ordinary civil courts, the Industrial Court cannot be approached directly by an aggrieved party unless the party has gone through the levels that have been discussed above (i.e. the conciliation stage, reporting stage, referral stage). Hence, in the case of Kathiravelu Ganesan & Anor v. Kojasa Holdings Bhd (Kojasa Holding Bhd case), the court held that the Industrial Court is only empowered to take cognizance of a trade dispute and adjudicate upon it only when the Minister makes a reference to the court. This is known as the “adjudication level”

In short, the representation made by the dismissed employee against the employer shall go through the levels below:-

Problem Statement

The “moneyed-employer” files judicial review against the Minister’s decision at the referral stage might causes the jobless employees who are poor engaging in an unequal legal battle against the employer. Other than that, regardless of finality clause (Section 33B IRA), the aggrieved party files judicial review under Order 53 Rules of Court 2012 against the Industrial Court’s decision on the ground of error of law. Judicial review affects the access to justice by the poor workmen, when they cannot afford highly escalated legal fees. Moreover, appellate processes under Order 53 Rule 9 Rules of Court 2012 against High Court’s decision is opened to abuse when the poor workmen forced to expend exorbitant costs for the prolong legal battle. Additional time and costs incurred caused halts the determination to seek for justice.

Research Questions

There are two (2) research questions to be determined in this study as follows:-

Whether judicial review and appeal against the Ministerial Reference causes unwanted delay and incurred exorbitant costs to parties seeking redress for wrongful dismissals?

Whether judicial review and appeal against the award of the Industrial Court prolongs litigation process and incurred high escalating costs to parties seeking remedies for wrongful dismissals?

Purpose of the Study

This paper will highlight the problems that happen at Ministerial referral level and also the issues after the decision or award is made by the Industrial Court after the adjudication level.

Research Methods

The theoretical framework of this research is mainly based on the Doctrinal Approach. By applying doctrinal approach to conduct this research, the authors had focused on the statutes mainly Industrial Relations Act 1976, case law and also other legal sources such as text books, journals and articles. The researcher had adopted this approach to be the starting point to conduct this research by studying the evolution of the law governing the ministerial discretion at referral levels, the development of the judicial review and appeal processes in relation to Industrial Dismissal Disputes in Malaysia. The analysis of the findings clearly justified in light of the underlying assumptions and limitations inherent in the research by assessing the past literary work, cases, statutes. The reason why the research selected library based research/doctrinal research is because the Research Questions for this study can be answered accurately by this approach and the Research Objectives for this study can be achieved by using this approach.

Findings

Ministerial Discretion at the Referral level

Prior to the adjudication of the disputes by the Industrial Court, the dismissal dispute shall be referred to the Industrial Court by the Minister of Human Resource pursuant to Section 20(3) of IRA. It is different from the ordinary courts of law where the parties to the dismissal dispute cannot bring their matter to the Industrial Court to adjudicate their dispute upon their grievances (Lim, 1999). The dispute will only be referred to the Industrial Court and such reference resembles a vehicle to carry the dispute to the Industrial Court to be adjudicated upon for a final and conclusive award after parties are unable to reach to an amicable settlement in negotiation and conciliation process (Chen, 2011). The Minister’s role is to filter out frivolous and vexatious cases to prevent from flooding in the Industrial Court (Anantaraman, 2003).

By virtue of Section 20(3) of IRA, the Minister of Human Resources is conferred with the discretion to decide whether to refer the representation of the workmen when he received the report from the DGIR pursuant to Section 20(2) of the IRA. According to the case of Minister of Labour, Malaysia v Sanjiv Oberoi & Anor (Sanjiv Oberoi case), the Minister is not required to give reasons while making a decision on whether or not to refer the case to Industrial Court. It was decided in the case of Wong Yuen Hock v. Syarikat Hong Leong Assurance Sdn. Bhd. & Another Appeal that once the representation made by workmen is referred by the Minister to the Industrial Court, the Industrial Court is obliged to determine the disputes on merit. Chang Min Tat FJ in the case Assunta Hospital v. Dr. A. Dutt held that the Industrial Court is seized with jurisdiction to hear the case once the dispute is being referred.

In the case of Abdullah Azizi Abd Hamid v. Menteri Sumber Malaysia & Anor, it is not the Minister’s duty to decide on the triable issues when deciding whether or not to refer the dispute to the Industrial Court under Section 20(3). The Minister only makes decision based on the conciliation report notified by the DGIR. In the case of Hong Leong Equipment Sdn. Bhd. v. Liew Fook Chuan and Another Appeal (Liew Fook Chuan case), the Minister is deemed to exercise his discretion properly by only looking at the evidences before the DGIR unless he had taken into account irrelevant matters and misdirected himself in law. The Minister’s role is confined to decide whether the facts and materials had before him raised a serious question of fact or law to be tried. The reference to the court by the Minister only states the names and addresses of the parties, the date of dismissal and the Minister’s opinion that the representation is fit to be referred to the Industrial Court (Lim, 1999). Hence, in deciding whether Minister had exercised their discretion in proper during judicial review, courts must not consider any evidence not raised before the DGIR in the conciliation proceedings as the Minister is only required to exercise his discretion based on the evidence and report of the DGIR that sets out the event occurred at the conciliation proceedings (Pathmanathan, Kanagasabai & Selvamalar, 2003).

However, it was held in Sanjiv Oberoi case that the exercise of Minister’s discretion is difficult to scrutinize when the court in the case of Sanjiv Oberoi ruled that the Minister is not bound to give reasons of the decision made by him. There is no statutory duty imposed on him and he cannot be compelled to do so. Later in the case of Liew Fook Chuan, Court of Appeal held that even though Minister may not be compelled by procedural laws to give reasons with regards to his decisions, the court may assume that the Minister has no reasons or inadequate reasons for the decisions he made and such decision shall be scrutinized. The court further added that the exercise of the discretion must be combined operation to the Article 5 and Article 8 of the Federal Constitution.

Unfortunately, such approach driven from the case of Hong Leong Equipment did not last long as in the case of Joseph Puspam v. Menteri Sumber Manusia Malaysia & Anor, the Court of Appeal decided that the ruling in the former case was not binding as the dicta of the Sanjiv Oberoi’s case is still a good decision (Anantaraman, 1999). Therefore, Minister is not obliged to give reasons for his decision on referring cases to the Industrial Court, but only expected to do so as per the case of The Minister for Human Resources v. Thong Chin Yoong & Another.

The problems of the Ministerial Discretion at the referral stage

A dismissal dispute only can be brought to the Industrial Court when the Minister refers the representation to the Industrial Court by exercising his discretion under Section 20(3) of IRA. However, the IRA 1967 does not list out the principles or guidelines to the Minister in exercising his discretion at the referral stage. In the case of Minister of Labour Malaysia v. Lie Seng Fatt at page 12 (1990) where the court commented that:-

“The minister had a discretion under Section 20(3) of the Act and that is not in dispute. The issue is whether the discretion is unfettered. To say it is an unfettered discretion is contradiction in terms. Unfettered discretion is another name for arbitrariness.”

The civil courts usually apply the Wednesbury’s principles when making decisions on whether the Minister had acted beyond his limits of his discretion conferred by the statute. Such principles were upheld by Lord Upjohn in the case of Padfield v. Minister of Agriculture Fisheries and Food & Ors. Decisions of the Minister can only be interfered when the Minister had given the wrongful directive order to himself in the point of law or had considered on irrelevant or extraneous deliberations; or wholly causing an omission to take into consideration a relevant provisions; or making decision that is contrary to the objective of the enabling statute (Dhillon, 2012).

As such, judicial review of the decisions made by the Minister on whether or not to refer the representation to the Industrial Court comes into the picture when the parties are at grievance to the Minister’s decision made under Section 20(3) of IRA (Anantaraman, 2003). There is no denying that such conferment of discretion to the Minister to refer or not to refer the dispute adds further unwanted delay in processing the disputes for reference to made to the Industrial Court. Even though the dicta of the case of Liew Fook Chuan had required the Minister to give reasons to carry out extra and diligent scrutiny of the case while deciding whether to refer or not, it imposes an additional delay in the referral stage (Anantaraman, 2003).

On the other hand, even though the Minister is not compelled to give reasons under the procedural law, in which the Minister is only expected to do so, the aggrieved parties may still seek for judicial review to challenge the Minister’s decision. The processing of the dispute in the Industrial Court will be stayed while pending of the disposal of the judicial review in the High Court (Ashgar Ali, 2010). The High Court will look into the preliminary questions arose and also taking into consideration whether the Minister had acted within his limit of his discretion under the law. Such review by the High Court does not look into the merit of the case and the court will only order certiorari to quash the decision made by the Minister if the High Court finds the decision made had acted beyond his limits. Subsequently, the High Court will order a mandamus if such dispute ought to be referred to the Industrial Court. Take note that the ultimate relief sought by the workmen had not being granted at this stage as judicial review challenged at this stage merely decides on the preliminary issues of the dispute.

Hence, case like Kumpulan Guthrie Sdn Bhd v. Miniser of Labour and Manpower, the dispute between the employee and the employer in this case had taken three (3) years for the dispute to be referred to the Industrial Court to be adjudicated upon. Subsequently, the employer in this case had challenged the reference on the ground of unwarranted delays on the reference. The High Court had refused to quash the reference on the said ground and ordered the case to be referred to the Industrial Court (Jain, 1997).

Furthermore, in the case of Kojasa Holding Bhd, the preliminary objection on whether Industrial Court has extra-territorial jurisdiction was raised by the employer after the representation to be reinstated of the employee was referred to the Industrial Court by the Minister. The reference was challenged up to the Court of Appeal and the court ordered the representation for dismissal to be remitted back to the Industrial Court to be adjudicated upon only after six (6) years from the date of dismissal (Ashgar Ali, 2010).

We cannot deny that judicial review at the referral stage is to scrutinize the Minister’s decision on whether they had exercised their discretion in accordance with law. However, it is important to note that when judicial review against the decision of the Minister at the referral stage, the dispute ought to be stayed. Thus, the existing mechanism of availability to seek for judicial review against the Minister’s decision might not be favourable to an aggrieved worker who is keen to seek for redresses of their dismissal by their employer without just cause (Ashgar Ali, 2010).

Other than inordinate delay caused by the judicial review against the decision of the Minister on the issue of reference of the dispute, parties might face high escalating legal fees while the dispute is brought up to the High Court for judicial review or even appeal. As such, the ill-afford workmen might face greater impact when they have to deal with high escalating costs to defend their suit in the High Court. Even though legal aids are available in Malaysia and parties are allowed to be represented by the Malaysian Trades Union Congress (hereinafter referred to as ‘MTUC’) for dismissal disputes at the Industrial Court, according to Third Schedule of Legal Aid Act 1971 (Act 26), the legal aid scheme does not cover cases like judicial review and the MTUC is not allowed to appear for cases in judicial review. Hence, the parties have to engage private legal practitioners in order to defend their case at judicial review and appeals in the civil courts (Dhillon, 2012).

Authors had highlighted that the unequal legal battle between the employer and employee happens when the employer is able to fund the legal costs for delaying tactics in litigation processes (Ashgar Ali, 2010). The employer will engage lawyers to act for them in challenging the preliminary issues after the reference made by the Minister by way of judicial review in challenging the technicalities (Dhillon, 2012). Take note that judicial review in High Court is unlike the proceedings in the Industrial Court. It is a court that involves complicated legal jargons and principles whereby an employee would definitely need to be represented by professional legal practitioners.

Moreover, parties who are not satisfied with the decision given in the judicial review may seek for appeal against the decision under Order 53 rule 9 of the Rules of Court 2012. In this situation, employee will still have to suffer additional unwanted delay in getting their recourse after dismissal. For instance, in the case of National Union of Hotel, Bar and Restaurant Workers v. Minister of Labour and Manpower, the dispute arose at the referral stage, when the parties were aggrieved by the decision made by the Minister for refusing the disputes to be referred to the Industrial Court. This matter was brought to the Federal Court. Later, the Federal Court had upheld the High Court’s decision and rejected the application (Wu, 1995). Therefore, the whole process for this preliminary issue to be resolved in the said case had to go through a lengthy litigation process.

Not only that, although cost of appeal will be awarded to the winning party, the employee still have to pay out substantially to their lawyers when confronted by all these legal battles. Such imbalance in the legal battle scenario was highlighted in the case of R Rama Chandran v. Industrial Court of Malaysia & Anor (R Rama Chandran case), where the court held that employers can always engage lawyers to prolong the litigation to burden the workers who can ill afford legal representation by lawyers

Decision and award under Section 33B of IRA – A Toothless Ouster Clause?

Section 33B of IRA states that an award or decision made by the Industrial Court shall be final and conclusive and cannot be challenged, appeal against, reviewed, quashed or called into question. This is to ensure the speedy disposal of Industrial disputes as the Industrial Court is intended to be the final avenue for disposal of dismissal disputes between the employer and workmen (Anantaraman, 2003). The ultimate purpose of the Industrial Court is to bestow an equitable, fair, cheap and swift redress to the parties. It is material to note that dismissal disputes heard before the Industrial Court are not to be bound by the procedural technicalities that are practiced by the civil courts (Altaf Ahmad & Nik Ahmad, 2003).

However, Malaysian judiciary more often ruled that this ouster clause in the Act does not protect the Industrial Court absolutely. The civil courts can scrutinize the Industrial court’s decision when the aggrieved parties challenge the decision by judicial review. Therefore, the courts are of the opinion that the function of the Industrial Court must be controlled and such powers that have been exercised must be proper and just (Dhillon, 2012). This could be supported by the case of Sabah Banking Employees Union, (Sabah Banking Employees Union v Sabah Commercial Banks Association, 1989) whereby Judge Abdul Hamid held that:

“it is fundamental to the Court’s constitutional and common law role as the guarantors of due process and the fair administration of law.”

It follows that if S33 may be disregarded, then the decisions of the Industrial Court may be challenged through judicial review under Order 53 of the Rules of Court 2012. It is not uncommon for a person aggrieved by the awards given by the Industrial Court to apply for an order of certiorari from the High Court to quash the decision made by the Industrial Court as stated under Order 53 r.2 of Rules of Court 2012

The wording of Order 53 Rule 2(4) of the Rules of Court 2012 is spelt out as below:

“(4) Any person who is adversely affected by decision, action or omission in relation to the exercise of the public duty or function shall be entitled to make the application.”

The Privy Council in the case of South East Asia Fire Bricks v. Non-Metallic Mineral Products Manufacturing Employees Union and Other held that the non-jurisdictional errors were not open to review (Abdul Hamid, 2008). The Malaysian Court can only review merely the jurisdictional errors of law appear on the face of the record. However, mere errors of law committed by inferior tribunals would not be subject to judicial review by the civil courts (Dhillon, 2012).

As a result, the implication brought by the Fire Brick’s case is that there is a distinction between jurisdictional errors of law appears on the surface of the record and mere error of law committed by the inferior tribunals. Review of the jurisdiction of inferior tribunal by the Malaysian Court can only be carried out when there are jurisdictional errors of law (Altaf Ahmad & Nik Ahmad, 2003).

Later, the Malaysian Court of Appeal is reluctant to follow the Fire Brick’s principles by ruling that the principle is no longer a good law to be followed. In the case of Syarikat Kenderaan Melayu Kelantan v. Transport Workers’ Union, Gopal Sri Ram JCA stated that:

“It follows, from what I have said, that the decision of the Board in the Fire Bricks and all those cases approved by it are no longer good law.”

The judicial review on the Industrial Court has now taken a new turn of event after the decision of the Federal Court in the case of R Rama Chandran was given. The Federal Court ruled that the when judicial review was carried out by the High Court on lower court’s decision, the court should try to provide remedy to any results which caused injustice when such unfair results is brought to the court’s knowledge. The court must not deny the relief to the aggrieved party on the narrow ground of technical error. Thus, the Federal Court held that:-

“to remit this matter back to the Industrial Court would mean to prolong the dispute which would hardly be fair or conductive to the interests of the parties… the court should determine the consequential relief rather than remitting the case to the Industrial Court for that purpose.”

This decision of the Federal Court in the case of R Rama Chandran had clearly departed from the original approach in judicial review that emphasizes on the rectifying the procedural defects. It is the right now the position of Malaysian civil courts to go further to remedy the substance or merit of each case in concern without having it to be remitted to the inferior tribunal such as the Industrial Court in order to be retrial (Dhillon, 2012).

Problems of Judicial Review against Industrial Court’s decision

The rationale of Section 33B of IRA was to ensure that the decisions of Industrial Court shall be conclusive and final in order to ensure that the dismissed workmen enable to get their redresses swiftly (Ashgar Ali, 2004). However, the civil courts that opened the gate to allow the Industrial Court’s decision to be reviewed under Order 53 of Rules of Court 2012 have caused several problems that contradict the intent of the IRA. Judicial review proceedings became the preferred route for the aggrieved parties to challenge the industrial court awards (Thiru & Das, 2013).

The High Court may exercise its powers of review when scrutinizing an Award of the Industrial Court pursuant to para 1 of Additional Powers of High Court in Schedule of Court of Judicature Act 1964 (Act 91). The problem arises when the technicalities of the courts of law are transposed onto the Industrial Court by the High Court when the Industrial Court was intended to be the court of equity and good conscience as spelt out under Section 30(5) of IRA (Thiru & Das, 2013). The case of Menara Panglobal Sdn Bhd v. Arokianathan Sivapirasagasam had observed that the Industrial Court is not supposed to be burdened with civil courts technicalities and procedures but to exercise based on equity and good conscience.

Furthermore, when the decisions or awards of the Industrial Court are meant to be conclusive and final pursuant to Section 33B of IRA, the civil courts in granting leave for judicial review to scrutinize such decisions or awards are not keeping in tandem with the spirit and intent of IRA (Anantaraman, 2003). The setting up of Industrial Court is to have a speedy disposal of trade disputes for the employees who had just been dismissed by their employer unfairly and they are looking forward and eager to get their redresses and remedy in swift manner (Ashgar Ali, 2004). A branched out tribunal for the workers separated away from the civil courts is to ensure such object can be achieved in our legal system. When the dismissal case is being brought up to the High Court, followed by Court of Appeal and lastly to the Federal Court, such dismissal disputes have been referred to the civil courts. It must be noted that administration of justice in civil courts, cover all causes of action. Thus, the judicial review of the dismissal disputes in the civil courts will cause more delay not only to the dismissal disputes but also other disputes as well when such additional bulk of the Industrial Court goes in to the civil courts.

In short, the existence of Section 33B of IRA which was to ensure the speedy disposal of dismissal disputes in the Industrial Court has now failed. It is consistently argued and held by the civil courts that this ouster clause cannot shelter the Industrial Court from judicial review even if the statute had declared an award is final and conclusive (ILBS Legal Research Board, n.d.). There is no doubt that the intention of Section 33B is to cut short, if not to prevent, the court in exercising the additional powers on judicial review against the Industrial Court’s decision, but the current is too strong to be stopped, this was mentioned in the case of Pendaftar Pertubuhan Malaysia v. PV Das (bagi pihak People’s Progressive Party of Malaysia (PPP)) (Datuk M Kayveas, Intervener). Such ouster clause had become a dead letter and the civil courts continue to expand the grounds for their interference

Appeal of Malaysia Industrial dismissal disputes

Pursuant to Order 53 rule 9 of the Rules of Court 2012, it stated that:-

“No setting aside of order. (O.53, r.9)

An application to set aside any order made by the Judge shall not be entertained, but the aggrieved party may appeal to the Court of Appeal.”

The available resort for the aggrieved party to file an appeal after judicial review is to appeal against the decision of Judicial Review to the Court of Appeal. This is because parties are not allowed to set aside the order under the Judicial Review.

The case of R Rama Chandran clearly illustrates the point of a very prolonged process when an Industrial Court Case can be challenged up to different tiers i.e. all the way to the Federal Court of Malaysia. Even though the appeal from the High Court should only be focusing on the process of decision-making by the Industrial Court, according to the case of Liew Fook Chuan, the court does not look at the process itself, but also at the merits of the decision. Instead of only quashing the decision of the Industrial Court, the court had acted further by remitting the case to the trial court. The civil court had decided to go beyond quashing the decision and granted consequential relief.

The case of R Rama Chandran was not only a landmark decision but was also a turning point in the aspect of Judicial Review. This case had broken new ground in asserting the legal power to grant consequential relief in judicial review proceedings instead of following the hallowed path of remitting the case to the original decision maker, a maneuver reminiscent of the exercise of appellate jurisdiction. It can be concluded that it appears to have a legal basis for the award of the Industrial Court to be analysed on the ‘substance’ as well as ‘processes’. The upshot of the award of the Industrial is that it is finely dissected and not only set aside, but substituted with an award of the court.

Problems of Appeal of Industrial Dismissal Disputes

The outbreak and development of law happened in R Rama Chandran’s case allows decision from supervisory courts to substitute the decision of the Industrial Court. (Thiru & Das, 2013) This decision is currently consistent with Order 53 rule 2 of the Rules of Court 2012. Be that as it may, it is the authors’ opinion that such development of law does not properly addresses the issues arose from the appeal against the decisions of judicial review related to industrial dismissal disputes. This decision may cause usurpation of the statutory functions of the Industrial Court (Thiru & Das, 2013). The main issue of exorbitant costs and unwanted delay suffered by the dismissed workers is not properly solved with this development of law. Parties are only able to get their redresses after a lengthy legal battle (Mills, 1984).

A series of cases shows that the dismissal disputes that gone through appeal undergo at least 7 years from the date of dismissal to get their matter to be finally disposed by the appeal court.

The table above shows that the dismissal disputes had taken a long time to be resolved. It is clearly tabulated that the inordinate delay is largely reflected in many cases and this issue cannot be resolved adequately by the development of law held in R Rama Chandran’s case. Even though parties are able to get their remedy at the final appeal stage when court can substitute the decisions of Industrial Court and not bound by ordering a certiorari, the parties had in fact waited for a very long period to get the reliefs. Although it can be seen as a quantum leap of law for the objective of cutting short the litigation process for not ordering the disputes to be retrial in the Industrial Court again, such periods faced by the litigants caused severe hardship for the workmen. Hence, the issue of unwanted delay and prolonged litigation is not properly resolved yet (Lobo, 2000).

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is the opinion of the authors that the current legal system for the adjudication of Industrial Court dismissal disputes is no longer suitable in the present industrial environment. The poor unemployed workmen that have just been unfairly dismissed have to go through lengthy litigation processes compared to the normal civil proceedings. The intent of IRA is to ensure a speedy disposal of dismissal disputes to safeguard and protect the interest of the dismissed workmen to be able to get their redresses and remedies (reinstatement or compensation) but in reality this notion is far from the truth.

This main objective, under current circumstances, is close to impossible, as most cases are being interfered by the higher civil courts. As discussed earlier, industrial dismissal disputes must be initiated at the Industrial Court which is a statutory tribunal regulating the industrial relations disputes. In order for the disputes to be adjudicated by the Industrial Court, the disputes must go through conciliation level, reporting level and referral level prior to adjudication stage. Once the case is decided by the Industrial Court, it is opened for the losing party to pursue judicial review against the decision. The parties that are not satisfied with the decisions of judicial review can also challenge the High Court’s decision by filing an appeal up to Court of Appeal and Federal Court.

As a result, it is very clear that the dismissal disputes filed by the worker had to go through much more levels compared to ordinary civil disputes. If this is the exact situation, the authors opine that something has to be done on the Section 20(3) of IRA and Section 33B of the IRA (Anantaraman, n.d.). Other than that, the scope of judicial review must be spelt out to specifically no interfere with the decisions of the Industrial Court. One may contend that such recommendations might infringe the constitutional right of the losing party to file an appeal or judicial reviews against the decisions which they are not satisfied with. Be that as it may, such constitutional protection has been abused by certain parties as part of their tactical maneuver in delaying the proceedings and creating an unequal legal battle against the poor workmen. The long episode causanaed by judicial review and appeals could be arguably assumed as a denial to adjudication when we subscribe to the legal maxim of “justice delayed is justice denied” (Kamal Halili, 2011).

To strike a balance between the parties, the authors do not suggest that the awards of the industrial court be prohibited for appeal completely, but in fact, recommend some changes that ought to be done onto the current industrial relations system of resolving disputes. The significant issues that must be curbed to begin with include abolishing the Minister’s discretion, dispensing away the prolonged litigation process of judicial review and appeal, and crushing the exorbitant costs that would have been incurred by the workmen in the pursuit of defending their cases in the upper civil courts. Thus, to cut short the litigation process and reduce the legal costs suffered by the workmen, it is our opinion that an Industrial Appeal Court be established to only hear dismissal disputes (The Star Online, 2014). Only when these issues are addressed properly, the industrial relations legal system in Malaysia will be consistent with the spirit of ‘equity and good conscience’ that the Industrial Courts ought to be with the original commandment of the Industrial Relations Act.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to record our deepest gratitude to Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE) for providing financial assistance to us in order for us to carry out the aforesaid research and writing this paper. The authors would also like to thank Multimedia University for providing us an opportunity to conduct this research.

References

- Abdul Hamid, M. (2008, March 5). Should The Industrial Court Not Be Allowed To Be What It Was Intended To Be? Retrieved from https://tunabdulhamid.me/2008/03/should-the-industrial-court-not-be-allowed-to-be-what-it-was-intended-to-be/

- Abdullah Azizi Abd Hamid v Menteri Sumber Malaysia & Anor [1998] 2 CLJ 297

- Altaf Ahmad, M. & Nik Ahmad, K. (2003). Employment Law in Malaysia. Petaling Jaya, Selangor Darul Ehsan: International Law Book Services.

- Anantaraman, V. (1999). The Enigmatic Law on Unfair Dismissals in Malaysian Industrial Relations, 2(1), 1–17.

- Anantaraman, V. (2003). Labour Relations in Malaysia: An Evaluation. Current Law Journal, 2, xxxvii

- Anantaraman, V. (n.d.). Malaysian Industrial Relations System: It’s Congruence with the International Labor Code a background paper on the Seminar. Retrieved from http://www.amco.org.my/n-archives/MalaysianIndustrialRelationsSystem-Anantaraman.pdf

- Ashgar Ali, A. M. (2004). A Critical Appraisal of the Adjudication Process of Dismissal under the Industrial Relations Act, 1967.

- Ashgar Ali, A. M. (2010). Judicial Review of Industrial Court Awards: Its Blemish and Proposed Reform, 1967.

- Assunta Hospital v. Dr. A. Dutt (1981). 1 MLJ 115

- Lobo, B. (2000). Current Trends in Judicial Review in Employment Law. The Journal of the Malaysian Bar, XXVIX (3), 18–34.

- Chen, V. S. (2011). Industrial Relations Law and Practice in Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur, WP: CCH Asia Pte Limited. Guru Dhillon. (2012). Current Judicial Review & Appeals in Industrial Relations Disputes - Unfairness of the Highest Order to the Workman. Legal Network Series, 1, xvi.

- Dhillon, G. (2012). Current Judicial Review & Appeals in Industrial Relations Disputes - Unfairness of the Highest Order to the Workman. Legal Network Series, 1, xvi.

- Hong Leong Equipment Sdn. Bhd. v. Liew Fook Chuan and another Appeal [1996] 1 MLJ 481

- ILBS Legal Research Board. (n.d.). Industrial Relations Act 1967 (Act 177) [With Notes on Cases], Practitioner’s Referencer. (ILBS Legal Research Board, Ed.). Petaling Jaya, Selangor Darul Ehsan: International Law Book Services.

- Joseph Puspam v Menteri Sumber Manusia Malaysia & Anor [2004] 4 MLJ 252

- Kamal Halili, H. (2011). The Rights of Litigants in Employment Dispute Resolution in Malaysia. LNS(A), 1, xx.

- Kathiravelu Ganesan & Anor v Kojasa Holdings Bhd [1997] 3 CLJ 777

- Kumpulan Guthrie Sdn Bhd v Minister of Labour and Manpower [1986] 1 CLJ 566

- Lim, H. S. (1999). The Role of the Industrial Court: Present and Future. Industrial Law Report, 1, i.

- Menara Panglobal Sdn Bhd v Arokianathan Sivapirasagasam [2006] 2 CLJ 501

- Mills, C. P. (1984). Industrial Disputes Law in Malaysia (2nd Edition). Kuala Lumpur, WP: Malayan Law Journal Sdn Bhd.

- Minister of Labour Malaysia v. Lie Seng Fatt [1990] 2 MLJ 9

- Minister of Labour Malaysia v. Sanjiv Oberoi & Anor [1990] 1 MLJ 112

- Minister of Labour, Malaysia v Sanjiv Oberoi & Anor [1990] 1 CLJ 200

- Jain, M. P. (1997). Administrative Law of Malaysia and Singapore (3rd Ed.). Kuala Lumpur, WP: Malayan Law Journal Sdn Bhd.

- National Union of Hotel, Bar and Restaurant Workers v Minister of Labour and Manpower [1980] 2 MLJ 189

- Padfield v. Minister of Agriculture Fisheries and Food & Ors [1968] 1 All ER 694

- Pathmanathan, N., Kanagasabai, S.K., & Selvamalar, A. (2003). Law of Dismissal. Singapore: CCH Asia Pte Limited.

- Pendaftar Pertubuhan Malaysia v. PV Das (bagi pihak People’s Progressive Party of Malaysia (PPP)) (Datuk M Kayveas, Intervener) [2003] 3 MLJ 449

- R Rama Chandran v Industrial Court of Malaysia & Anor [1997] 1 MLJ 145

- Sabah Banking Employees Union v Sabah Commercial Banks Association [1989] 2 MLJ 284

- South East Asia Fire Bricks v. Non-Metallic Mineral Products Manufacturing Employees Union and Other [1981] A.C. 363

- Syarikat Kenderaan Melayu Kelantan v. Transport Workers’ Union [1995] 2 MLJ 317

- The Minister for Human Resources v. Thong Chin Yoong & another [2001] 4 MLJ 225

- The Star Online. (2014, June 23). Call for labour appeals court. The Star Online. Kuala Lumpur. Retrieved from http://www.thestar.com.my/News/Nation/2014/06/23/Call-for-labour-appeals-court-Move-will-help-resolve-workrelated-disputes-faster-says-judge/

- Thiru, S. & Das, G. (2013). Employment and Industrial Relations Law in Malaysia. (Cyrus Das, Ed.). Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia: The Malaysian Current Law Journal Sdn Bhd, Malaysian Society for Labour and Social Security Law.

- Wong Yuen Hock v Syarikat Hong Leong Assurance Sdn. Bhd. & another Appeal [1995] 3 CLJ 344

- Wu, M. A. (1995). The Industrial Relations Law of Malaysia. Cheras, Selangor Darul Ehsan: Longman Malaysia Sdn Bhd.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 December 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-051-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

52

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-949

Subjects

Company, commercial law, competition law, Islamic law

Cite this article as:

Dhillon, G., & Juet*, P. J. (2018). The Legal Process Of Industrial Dismissal Dispute In Malaysia –Need For Reform?. In A. Abdul Rahim, A. A. Rahman, H. Abdul Wahab, N. Yaacob, A. Munirah Mohamad, & A. Husna Mohd. Arshad (Eds.), Public Law Remedies In Government Procurement: Perspective From Malaysia, vol 52. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 267-269). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.12.03.26