Abstract

The term Procrastination describes a complex disturbance in the process of controlling action and is associated with low self-regulation capacities. Especially among students for whom 75 percent report being negatively impacted by the tendency. The study at hand tests the theory that meditation supports self-relational capacities among students, and therefore leads to a reduction in procrastination behavior. Eight semi structured interviews were conducted with students experienced in meditation (N=8, age= 20-25 years). The students were instructed to reflect on their meditation practice and its possible influence on their study habits, especially procrastination. Qualitative content analysis revealed the following main factors on the relationship between the effectiveness of meditation and procrastination: time-management, focus of attention, self-regulation, pressure to perform, self-worth and acuteness of thoughts. Further, to investigate procrastination among the participants the Tuckman Procrastination Scale (TSP-D) was included. The quantitative results indicate, that the participating students, who are experienced in meditation show a very low score on procrastination. In conclusion, the study suggests that mediation is associated lessened procrastination with possible mechanisms of increased acuteness of thoughts, focus of attention and self-regulation.

Keywords: Contemporary academic learning; meditation; procrastinationself-regulation

Introduction

Students have a busy and varied life that involves dealing with many diverse responsibilities such as writing papers, study for exams, and many other tasks which require self-regulation. Procrastination refers to performing tasks other than the ones the person intends on spending their time on such as washing the dishes, cleaning their house or joining in sports. The meaning of the word “procrastination” comes from the Latin words “

Problem Statement

To postpone an action to another point of time is in itself not problematic. In fact, the conscious decision of attributing importance to one action instead of another—therefore choosing to do other things first—could be regarded as an act of self-regulation. The problem arises, when the intended, but postponed, action is not executed, and in its place a different and less important task fulfilled. Those that tend to procrastinate tend to have less active control of their actions and thus tend to put of the initially intended action. Procrastinators tend to experience stress, a loss of time-management, inconsistency in their actions and feel bad about their procrastination behavior (Rückert 2014). Almost 75 % of the college students report procrastination behavior hindering their studies (Höcker et al. 2013). Steel (2005) found that 95 percent of a student sample see themselves as procrastinators with a motivation to reduce the behavior.

In attempting to explain procrastination behavior affective, cognitive and motivational explanations need be taken into account. Self-doubt appears to play a major role, especially among students (Höcker et al. 2013; Solomon, & Rothblum, 1984). A behavioral account could explain the origin of the problem, such that the act of postponing an action and not being able to pursue the intended task at a chosen point of time, the person in question loses control of the chain of action. During the normal course of life, decisions between the urgencies of taking different actions need to be taken continuously. As Höcker (2013) stated, these decisions are highly influenced by the current mood, the anticipation of success and failure, and the expected influence of the action on the mood. Further, a cost-benefit ratio of the immediate or postponed fulfillment of the task is being executed (Höcker et al. 2013). If the person keeps on choosing rather the task that seems to be most attractive based on mood, instead of choosing the most exigent and intended task, the postponing becomes a procrastination problem (Höcker et al., 2013). Deci and Ryan’s (2000) theory of self-determination proposes different psychological needs that motivate behavior. Of particular relevance to procrastination is the distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Extrinsic motivation is present in circumstances where the goal of an action lies out of the range of the act itself. An extrinsic motivation for a student to study could be the anticipated social appreciation of his future position:

Baumann & Kuhl (2013) found, that internalization can enhance intrinsic motivation through self-knowledge which can be supported by meditation. Further, neuropsychological findings on the effect of meditation show increasing activity in brain areas—especially in the medial praefrontal cortex—associated with emotional regulation and self-regulation (Hölzel et al., 2007; Hölzel et al., 2011;). Fianly, meditation practitioners show more activation at the anterior cingulum what leads to the conclusion, that meditation practitioners have more attention regulation and are less easy disturbed (Purdy, 2013) .

Research question

If motivation and self-regulation seem to play a major role in procrastination behavior, and meditation practice seems to lead to a better attention-, emotion- and self-regulation:

Do meditation practitioners display lower rates of procrastination?

Purpose of the Study

The study investigates the experienced effects of meditation on procrastination behavior among current students.

Research methods

A qualitative research paradigm was used to investigate the first hand experiences of current students. The study aims to understand how the participating students derive meaning from their behavior, and how their behavior influences their actions. The research question focuses on the experienced effects by students who practice meditation from a self-reflection perspective. For this reason, a semi structured interview scheme with open questions was developed. The interviews were taken with students, who are experienced in meditation, transcribed with support of the software F5 and based on Mayring (2000) content analyzed with the software Atlas TI V.7 . The German Version of the Tuckman Procrastination Scale (TSP-D) was included to quantify procrastination among the participants and analyzed by using SPSS for Windows V21.

5.1 Instruments

5.1.1 Interview scheme

The students were invited to reflect on their meditation practice and a possible interrelation with their study habits and especially procrastination. Based on a literature-review on procrastination and meditation an interview scheme was developed, consisting of four thematic sections: (a) warm up: definition meditation (b) perceived effects of meditation in general (c) perceived effects of meditation on study/procrastination (d) summary.

The interview scheme was meant to provide a guideline throughout the interview, but followed the principle of open and theory generating research. Thus process orientated adaption of questions based on the content of the participants’ answers was possible.

5.1.2 TSP-D

The German version of Tuckman’s scale to measure procrastination is a 16 item scale with a possible range from 16 to 80 points using a 5 point likert-scale. A higher score indicates a higher amount of procrastination (Tuckman, 2002). The analysis of the TSP-D is conducted by adding the raw scores of the 16 items, reversing 7, 12, 14 and 16.

5.1.3 Sample description

The following inclusion criteria were devised: (a) participants must be students whose curriculum is at a point where exams must be written—to ensure that a certain degree of pressure within periods of intense learning; (b) participants need to have practiced meditation at least for the last eight weeks—a minimum period of time to show effects of meditation (Berking, & Känel, 2007); (c) a counterbalanced gender ratio; and (d) a well-balanced ratio of different courses of study.

The sample consists of eight students, four male, four female, aged 20-25 years old, studying psychology, medicine, economy, and culture. According the inclusion criteria, all participants practiced meditation at least eight weeks before the interview. Psychology students had the option to gain research credit points for their curriculum by participating.

Findings

6.1 Demographics

The participants (N=8) age ranged between 20-25 years (µ = 22, SD = 1,41). The meditation experience ranged between seven months and four years. The current practice varied between 0,5 times a week for 60 minutes till 7 times a week for 60-120 minutes meditation practice. The mean amount of practice was 4,81 times a week (σ =2,20). The duration of the interviews varied between 19:14 and 43:55 minutes.

6.2 TSP-D

The quantitative analysis showed results ranging between 22 – 44,5 (mean= 29,88 ; σ = 6,80). Tuckman (2002) proposes the following classification for the grade of procrastination based on it standardized questionnaire: 80-64= very high; 64- 57= high; 56- 50= moderate; 49-35= low. With an average result of mean=29,88, the participants within this study scored very low on procrastination tendencies. The quantitative results indicate, that the participating students, who are experienced in meditation show extreme low levels of procrastinate.

6.3 Interviews

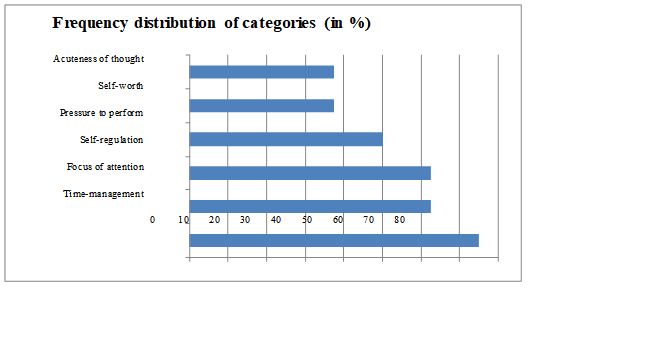

The qualitative content analysis depicted a very homogenous picture of the experienced effects of meditation, and the interrelation between meditation and procrastination. The following main factors of meditation were depicted by the participating students as playing a major role influencing their procrastination behaviour:

To test for the interrater-reliability another researcher, well experienced in qualitative research, coded the interviews. The interrater-reliability was 73% (Cohens Kappa κ=0,7). So the researchers consistently coded the developed categories that can be regarded as substantial (Landis, & Koch, 1977).

6.4 Acuteness of thought

Three participants (37,5%) state that by practicing meditation, they improve their ability to arrange their ideas and thoughts. Through meditation, they can see clearly what they want to do or what they need. For participant CZ23 this comes along with the feeling of not connecting her („her“ is used to refer to all participants, the participants gender cannot be drawn from this ) feeling of self-worth with the learning task. VH71 states, that by meditation ones feelings can be controlled what makes her free of distracting thoughts when planning to study.

6.5 Focus of attention

Five participant (62,5%) report an increasing ability to focus their attention and to concentrate easier. 12 paraphrases depict, that the participants can study more effective, more concentrated and less interrupted.

6.6 Self-worth

37,5% of the participants declare to stable their feeling of self-worth by practicing meditation. This comes along with a no judging state of mind towards negative feelings about oneself and an acceptance of one’s impairment as participant MG13 stated.

6.7 Self-regulation

Without being asked about self-regulation, 62,5% of the participants report an increased ability to self-regulate as and perceived transformation through meditation. When being asked for the interrelation between self-regulation and meditation, all participants acknowledged ascertaining this. Intrinsic motivation, self-determination and the acceptance of aversive tasks is supported by meditation as participant MG13 pointed out. Emotional regulation is regarded as a part of self-regulation as five participants depicted. HH59 stated that by facilitating self-perception through meditation, the ability to regulate her emotions is strengthened. By deductive reasoning she states, meditation operates on her general state of mind and a conscious attitude so regulation comes with conscious decision making.

6.8 Decreasing pressure to perform

Four out of eight (50%) participants describe, that because of practicing meditation they experience less pressure while studying. Getting started for studying becomes easier, because of a reduced experienced amount of expectations, as CZ23 states. The participants experience a general feeling of relaxation through meditation practice what releases tension from the learning process.

6.9 Time-management

75% of the participants interrelate the effects of their meditation practice on their learning behavior with their ability to manage their time. By practicing meditation on a regular base, they increase their general reliability, regularity and structure. By this, procrastination does not occur that often, MG13 stated.

Conclusions

The results provide confirmatory evidence for the theoretical overlap between procrastination and meditation. As depicted in the results of the TPS-D, the meditating students participating in this research show extremely low levels of procrastination. The preceding analysis of the interviews shows, that the participating students know about the concept of procrastination, the interdependency of meditation, and the lack of procrastination problems. The experienced effects of meditation are in line with the results of current findings on meditation, what underlines the hypothesis that meditation could have a positive effect on the student’s behavior to reduce procrastination. However, the sample is quite small and the results needs to be verified in a larger sample with the use of standardized questionnaires. Interventional studies could also be used to test the hypothesis.

As Meibert et al. (2006) describes, the capacity to concentrate, and the acuteness of thought seem to relate to the feeling of insight in one’s inner feelings and drives, their values and intrinsic motivation that are stimulated by meditation (Meibert et al. 2006). The participants describe this as a major factor for their lack of procrastination behavior. In the literature the question of intrinsic versus extrinsic motivation for a task is crucial for the occurrence of procrastination (Deci, & Ryan 2000). Additionally, self-regulation is associated with procrastination (Höcker et al., 2013), and is positively influenced by meditation, as is suggested by the interviews in this study. The participants describe that their self-regulation especially influences attention regulation, the regulation of emotions (like anxiety), and their self-perception. Procrastination is about the intention to fulfill a task and instead of fulfilling the intended task, another, mostly unimportant task is fulfilled. If the alternative task is perceived as more attractive, and the intended one as aversive, procrastination is more likely to occur. Meditating students seem to be able focus their attention better on an intended task, and don’t feel disturbed by alternative tasks. They feel more self-confident and experience less anxiety, which is another explanation for procrastination among students (Höcker et al., 2013). The participating students explained that by meditation their emotional regulation is strengthened. Disturbing emotional states are perceived as less disturbing, and by controlling their focus of attention, meditating students can stick to their planned tasks and do not get caught up with alternative tasks.

7.1 Prospect

The results indicate that the hypothesis that meditation could have a positive effect on procrastination or could even prevent procrastination is worth further investigation. Future confirmation of this hypothesis could influence university policies to consider motivating their students to engage in meditation practice. Special meditation training could be part of the curriculum to help students to improve their self-regulation, intrinsic motivation, and concentration to prevent procrastination behavior.

References

- Baumann, N. & Kuhl, J. (2005). Selbstregulation und Selbstkontrolle. In H. Weber &

- Rammsayer (Hrsg.), Handbuch der Persönlichkeitspsychologie und Differentiellen Psychologie (S. 362-373). Göttingen: Hogrefe.

- Berking, M. & Känel, M. (2007). Achtsamkeitstraining als psychotherapeutische

- Interventionsmethode: Konzeptklärung, klinische Anwendung und aktuelle

- empirische Befundlage. Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik, Medizinische Psychologie, 57, 170-177.

- Brahm, T. & Gebhardt, A. (2011). Motivation deutschsprachiger Studierender in der

- „Bologna-Ära“. Zeitschrift für Hochschulentwicklung, 6 (2), 15-29.

- Höcker, A., Engberding, M. & Rist, F. (2013). Prokrastination: Ein Manual zur

- Behandlung des pathologischen Aufschiebens. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

- Hölzel, B. K., Lazar, S. W., Gard, T., Schuman-Olivier, Z., Vago, D. R. & Ott, U.

- (2011). How does Mindfulness Meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6 (6), 537-559.

- Hölzel, B. K., Ott, U., Hempel, H., Hackl, A., Wolf, K., Stark, R. & Vaitl, D. (2007).

- Differential engangement of anterior cingulate and adjacent medial frontal cortex in adept meditators and non-meditators. Neuroscience Letters, 421, 16-21.

- Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. biometrics, 159-174.

- Meibert, P., Michalak, J. & Heidenreich, T. (2006). Stressbewältigung durch

- Achtsamkeit. Psychotherapie im Dialog, 7 (3), 273-278.

- Purdy, J. (2013). Chronic Physical Illness: A Psychophysiological approach for chronic

- physical illness. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 86, 15-28.

- Rückert, H.-W. (2014). Schluss mit dem ewigen Aufschieben: Wie Sie umsetzen, was Sie

- sich vornehmen (8. Aufl.). Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag GmbH.

- Senécal, C., Koestner, R. & Vallerand, R. J. (1995). Self-Regulation and Academic

- Procrastination. Journal of Social Psychology, 135 (5), 607-619.

- Stöber, J. (1995). Tuckman Procrastination Scale-Deutsch (TPS-D). Unveröff.

- Manuskript. Freie Universität Berlin, Institut für Psychologie.

- Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of

- Intrinsic Motivation Social Development, and Well-Being. American Psychologist, 55 (1), 68-78. doi:

- Tuckman, B. W. (1991). The development and concurrent validity oft he

- Procrastination Scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 51, 473-480.

- Tuckman, B. W. (2002). Academic Procrastinators: Their Rationalizations and

- Web-Course Performance. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Association, Chicago.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

22 November 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-015-0

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

16

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-919

Subjects

Education, educational psychology, counselling psychology

Cite this article as:

Thye, M., Mosen, K., Weger, U., & Tauschel, D. (2016). Meditation and Procrastination. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, & R. X. Thambusamy (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2016: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 16. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 65-72). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.11.8