Abstract

The article discusses the peculiarities of the sociocultural identity of young people in a situation of moving to another country: from Russia to Finland and Germany. The importance of the proximity of the language and culture of the two countries is shown – the country from the young people came from and the one to which they emigrated. The significant role of a positive emotional attitude towards native and new cultures is revealed. The results of an empirical study of young people of Karelian and German nationality who lived in Russia and moved to Finland and Germany, respectively (N = 100 Karelian and N = 100 Germans) are presented. During the study, data were obtained on the attitude to the native and foreign culture, as well as materials revealing the structure of sociocultural identity and attitudes towards people of a foreign culture. The results confirmed a close relationship between the attitude to the new culture and language and the degree of socialization in the new country. Knowledge of the language, norms and standards of a new country not only helps acculturation, but also forms a positive attitude towards the culture and country of new residence in general. The proximity of cultures, as well as the characteristics of interpersonal communication, which allows establishing interpersonal relationships among peers, plays a large role in the formation of this positive attitude. Such relationships help to overcome the alienation between a person and the new social situation and reduce ethnocentrism.

Keywords: Crisis transitivityethnic identityethnocentrismsociocultural identity

Introduction

Culture as identity formation factor

At present, for many Russians who find themselves in a new social situation that forces them to adapt to unusual conditions, the very fact of socialization, and the difficulties and deviations that arise in this process, are only partially recognized (Belinskaya & Dubovskaya, 2009). And in this situation, acculturation, acceptance and appropriation of culture are one of the important factors determining the success of socialization in the new conditions (Andreeva & Dontsov, 2002). Native culture, language “absorbed with mother’s milk” from an early age and remain unchanged in a changing world; this constancy distinguishes enculturation from other types of social adaptation (Martsinkovskaya & Siyuchenko, 2014). Therefore, acculturation gives the rooting and stability necessary in today's life, which is perceived by many as broken, indefinite. In the case of successful enculturation and / or acculturation, culture is emotionally perceived as a whole, however person needs to realize (independently or with the help of other, for example, adults, teachers) the connection of culture with different periods of Russian history - ancient, pre-revolutionary, Soviet and modern, and also highlight certain historical characters through emotional identification with which different structures of self-awareness can be formed (national, legal, personal). Thus one of the most important components of the structure of self-identity is formed - “I am a cultured person”.

Social identity in new crisis situation

For many decades, sociocultural identity has been formed in a stable world, with stable ideas of people about norms, values, ideals, with a stable image of the world - both physical and spiritual. In current decades, globalization and mass migration processes have significantly shaken not only the image of the world, but also self-image, the sociocultural identity of many people. The transitivity of the modern world, variability and uncertainty sets many different options for combining personal, linguistic, social and cultural identities, the infinite variety in the ratio of its types, the instability of the balance of identities (Martsinkovskaya, 2015).

At present, for many Russians, who find themselves in a new sociocultural situation that forces them to adapt to unusual conditions, the very fact of socialization, and the difficulties and deviations that arise in the formation of a new identity, give reason to assume that this situation for them is a situation of crisis, rigid transitivity.

In this situation, acculturation, acceptance and appropriation of a new culture are one of the important factors determining the success of the formation of a new identity. Culture, language, art, remains unchanged even when life, worldview, and social environment of a person change. This constancy distinguishes culture as a factor that helps to “restore the connection of time,” namely, a culture that is emotionally perceived as a whole, as part of social, ethnic and personal identity, gives root and stability, allowing to find points of support in a changing reality and restore lost integrity of perception peace and one-self.

Therefore, it is culture that can become the basis for the formation of the sociocultural identity of people in a new situation. Since the formation of a sociocultural identity is impossible without internalizing external requirements, turning them into intentions, motivation and values of people, the most important question arises about the psychological mechanisms that contribute to the transition of these requirements into the internal structure of the personality. Such a mechanism can be emotional experiences (both positive and negative) that form personal attitude towards the norms, values and rules adopted in society. These emotional experiences, in contrast to emotions mediating a person’s attitude to vitally important things for him personally (food, danger, etc.), can be called social (Martsinkovskaya, 2015).

At the same time, cardinal changes in crisis transitivity associated with moving to another country with a different culture and language pose new problems for people, since the basis for the establishment of a sociocultural identity must be radically or at least partially transformed (Martsinkovskaya & Solodnikova, 2018). Therefore, the problem of studying the specifics of the structure and content of identity of people living in a new ethnic and cultural environment, as well as how the process of transformation of social identity in people changing their living conditions, city, country, culture, is currently becoming efficient. To a large extent, this question arises for people who change their country of residence in adulthood. This drastically changes the idea of one’s own and another’s culture, even if the culture and customs of the new environment are familiar. The specificity of studying the social identity of “Russian Germans” is that we are dealing with representatives of the same ethnic group, having the same historical roots but different social experiences of recent decades, which, in our opinion, should determine the differences in socialization and constructing the image of them-selves and the image of the world (Kiseleva & Orestova, 2018). Therefore, it can be assumed that the central element of the new sociocultural identity, especially in the first time after the move, is not the language or culture as a whole, but the family, which provides the basis for being rooted in the new sociocultural environment.

Problem Statement

Enculturing people when moving to a new place of residence is always a complex and painful problem. Moreover, resocialization becomes even more difficult when moving to another country, with a different mentality, language and culture. The fact that this culture and language is partially native to people who ethnically belong to it, but who were born and lived for many years in another country, often does not simplify, but, on the contrary, complicates socialization and acculturation in a new environment.

Research Questions

The main research questions are related to the study of factors that optimize the process of acculturation and resocialization in a new country.

How does the attitude to language and culture influence acculturation in a new country?

How knowledge of the language, etalons and norms affects the attitude towards people of another culture?

Purpose of the Study

In the context of this study of the features of socialization in a multicultural transitive space, we set two tasks: to identify the specifics of the change of attitudes to others after changing the place of residence and to analyze the dynamics of ethnocentrism in different regions.

Research Methods

To study the content of ethnic and sociocultural identity, the method “Features of Ethnic Identity” was used;

To study attitudes toward native and foreign cultures, the “My Culture” method was used;

To study ethnocentrism, we used the method “Ours — strangers”.

All participants knew about the aim of the study and agreed to participate in it.

Findings

Attitude to native and foreign language and culture

In the course of the study, data were obtained on the attitude to the native and foreign culture of respondents living in different regions and having changed or not changed their place of residence.

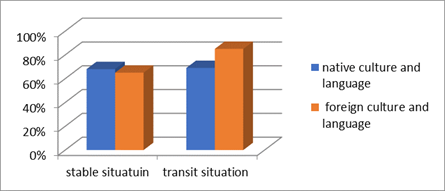

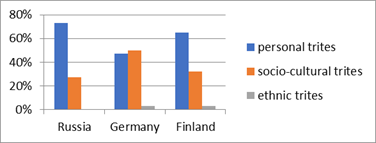

The materials obtained showed that among the Karelian youth who moved to Helsinki, a positive attitude towards a foreign culture is increasing. At the same time, a positive attitude towards the native culture does not decrease, although it does not grow (fig.

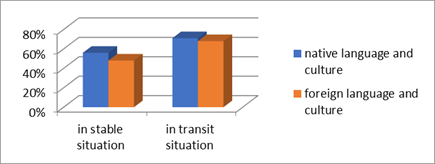

German youth who moved to Germany also do not reject another culture. At the same time, with the Germans who moved to Germany, a positive attitude towards Russian culture grows a little more than positive attitude towards German culture. Of interest in this regard is the fact that before moving both cultures were considered as native. After moving to Germany, we can see the division into Russian (old, native) and German (new, native-foreign) cultures. It is noteworthy that almost all respondents identify culture with language (fig.

Increasing of the positive attitude towards a foreign culture shows a good level of socialization in a new place of residence. On the contrary, a decrease in positivity, sometimes even emotional rejection with a sharp increase in status and an emotionally positive attitude towards native culture, is usually an indicator of nostalgia and low acculturation in a new place or a new sociocultural situation.

These materials correlate well with the data obtained in the study of the structure of sociocultural identity.

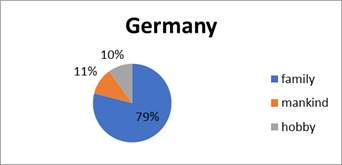

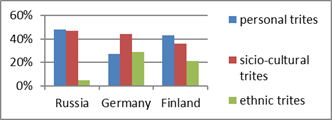

The difference in the degree of socialization is evidenced by the fact that for the German sample, regardless of place of residence, the family is in the first place (fig.

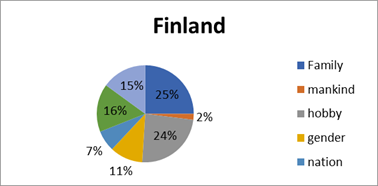

On the contrary, the Karelian language helps a lot of young people to adapt well in Finland, especially since many people know Finnish quite well. They are also fluent in Russian, which for most young people is, in fact, native (and even more native) than Karelian.

Therefore, they are well socialized in Helsinki, and the structure of their sociocultural identity is significantly different from the young people who moved to Germany (fig.

Culture and ethnocentrism

During this part of the study participants were asked to answer the question of how they are seen by people of the same cultures and people of other cultures.

As can be seen from the results, people assume that representatives of the same culture see them as individual and evaluate, based primarily on their personal, rather than role or sociocultural characteristics. Interestingly, in Russia, when assessing people of one culture, there are no ethnic characteristics that, albeit to a small extent, are present when they evaluate people of another culture. It is also interesting that in Germany personal and sociocultural characteristics are present almost equally (fig.

No less interesting are the results of the answers to the second question. Most respondents believe that people of a different culture will see individuals in them, and not representatives of another, alien large group. Despite a significant increase in assessments related to ethnicity, personal and sociocultural characteristics dominate in this case as well (fig.

Thus, we can say that the assessment of people of a different nationality is affected by the typical effects of the psychology of social cognition (Andreeva, 2000).

Conclusion

The obtained results confirmed the close connection between the ideas about language and culture that exists among the majority of respondents. It should be noted that this connection is actualized in most people in a situation of severe transitivity, in particular, when moving to another country or changing sociocultural situation. At the same time, for many, culture is identified with the language, and therefore the absence or lack of knowledge of a foreign language is a fact that reduces the positive attitude towards the new culture. On the contrary, raising the status of culture (both one's own and another's) is an important factor helping acculturation in a new place of residence.

Acceptance of a foreign culture, associated with an increase in a positive attitude towards it, can be considered as a factor of good socialization in the new situation. The low level of acculturation and nostalgia for the old time and the past situation are associated with an increase in a positive attitude towards native culture with the increase of negative attitude towards a foreign culture and language.

The low acculturation and low level of socialization as a whole is also evidenced by the small number of identity groups in the structure of sociocultural and ethnic identity. Moreover, the dominant place of the family in this structure is a clear phenomenology of emotional discomfort.

Attention is drawn to the fact of a significant discrepancy between the assessment of specific people of a foreign culture and the general assessment and attitude to a large group of people of a different culture and language. This fact, known in the social psychology of cognition, increases significantly in a situation of transitivity and interethnic interaction, which becomes in many ways the reason for the increase in ethnocentrism.

References

- Andreeva, G. M., & Dontsov, A. I. (2002). Sotsial'naya psikhologiya v sovremennom mire [Social psychology in the modern world]. Aspekt Press.

- Andreeva, G. M. (2000). Psikhologiya sotsial'nogo poznaniya [The psychology of social cognition]. Aspekt Press.

- Belinskaya, E. P., & Dubovskaya, E. M. (2009). Izmenchivost' i postoyanstvo kak faktory sotsializatsii -lichnosti [Variability and constancy as factors of socialization of an individual]. Psikhologicheskie Issledovaniya, 5(7), 2. http://psystudy.ru

- Kiseleva, E. A., & Orestova, V. R. (2018). Spetsifika sotsial'noy identichnosti etnicheskikh nemtsev, prozhivayushchikh na raznykh territoriyakh [The specifics of the social identity of ethnic Germans living in different territories]. Psikhologicheskie Issledovaniya, 11(58), 5. http://psystudy.ru

- Martsinkovskaya, T. D. (2015). Modern psychology - the challenges of transitivity. Psikhologicheskie Issledovaniya, 8(42), 1. http://psystudy.ru

- Martsinkovskaya, T. D., & Siyuchenko, A. S. (2014). Identichnost' kak faktor sotsializatsii v polikul'turnoy srede [Identity as a factor of socialization in a multicultural environment]. Voprosy psikhologii, 6, 3-14.

- Martsinkovskaya, T. D., & Solodnikova, I. V. (2018). Transformatsii sotsiokul'turnoy i yazykovoy identichnosti v protsesse sotsializatsii v polikul'turnoy srede [Transformations of sociocultural and linguistic identity in the process of socialization in a multicultural environment]. Psikhologicheskie Issledovaniya, 11(58), 4. http://psystudy.ru

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

15 November 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-093-8

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

94

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-890

Subjects

Psychology, personality, virtual, personality psychology, identity, virtual identity, digital space

Cite this article as:

Martsinkovskaya, T., Kiseleva, E., Markovskaya, O., & Gavrichenko, O. (2020). Sociocultural Identity In A Situation Of Crisis Transitivity. In T. Martsinkovskaya, & V. Orestova (Eds.), Psychology of Personality: Real and Virtual Context, vol 94. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 474-480). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.11.02.58