Abstract

The article reveals an algorithm for creating news under the conditions of abundance of information; the use of this algorithm provides an increase in the audience attention to media texts. The problem of analyzing a media text semantic space and defining its linguocultural determinants is one of the leading themes in the digital era. The problem is associated with the educational process reform - from primary to higher education. When exposed to digital technologies, the forms of learning are changed dramatically, and the issues of cognitive perception and assimilation of information step forward. Nowadays, the priority is given to distance learning with the dominance of indirect communication in subject-subject and object-subject interaction. This type of learning is transformed into virtual communication (the use of computer and VR technologies), which takes place both in intrapersonal and person-to-person communication, and in the form of group and mass communications, which requires the interdisciplinary knowledge and new teaching methods. The study of media text semantics and structure regardless of the form of media content representation (speech, print, visual, multimedia, virtual), allows tracing the effectiveness of the information impact on perception and reflection of an individual, identifying the degree of his/her involvement. The study applies semantic analysis, indicating the need to predict integration of communicative effects and media text semantics at the preparatory stage, to increase final indicators of its cognitive impact on a recipient. The algorithm presented in the article is recommended for study when training journalists and other specialists in mass communications.

Keywords: Media textcommunicative effectdigital consumption

Introduction

Fundamental transformations of the modern media space, significantly complicated when driven by high technologies, cause the acceleration of production processes, popularization and updating of all types of event information (verbal, graphic, sound, numerical, video information) in accordance with digital era challenges. This is connected not only with the progress, living standards improvement and the individual’s seek for getting involved in modern age, but also with the meaningfulness of the era, which, according to the Russian scientist S.P. Kapitsa, is expressed “in vocabulary, judgments, symbols, images, concepts, focusing on popularized information within the knowledge of generation, which are improved and updated from era to era” (as cited in Urazova, 2015, p.21).

Modern media structures, producing and distributing media products, searching for effective methods of involving and immersing a consumer in the mass communication paradigm are interested in activating the attention of different social groups to published information. However, their aims are most associated with the development of the media business that results in adaptation of advertising and PR-elements in the media text that formalize the content of information, which cause mass media without masses. The problem of concentration of media consumers' attention on released information products and recognition of their meanings is correlated with the survival of mass media on the media market, marked by increased competitiveness.

Nevertheless, the information flows redundancy generates a contradiction, the consumer becomes tired due to diversity of media products and shows selectivity when addressing it. As a result, the user starts evaluating the information in order not to waste his/her free time, or simply ignores it. Such a psychological protest in media and social space raises the issue about the quality of information, its self-descriptiveness, freshness of its form, but most importantly, it speaks for the low effectiveness of institutional and auditorial (object-to-subject) communication in general. This aspect of the problem is projected onto the field of education as well. In the digital age, where information grows at an exponential rate, it forms a whole range of discursive issues. They affect both the training of new-breed journalistic personnel and the formation with them of updated professional competencies, skills of communicative culture, individual style, that is, the modern level parameters that are necessary when creating a media text (media text, media construct). Media text is understood in its broad meaning and includes all types of media production (print, television and radio broadcast, Internet communication, multimedia content, video production, film, etc.).

Problem Statement

Following the use of digital technologies, the modern media space, perceived as a subsystem of information and communication universe has acquired multimedia and multi-platform qualities. Such a diversification, it should seem, has a multiple spectrum of diverse media information for building productive relations between the mass media and consumer communicators. However, the time for the perception of information is significantly reduced due to the acceleration of its rotation, which results in mental discomfort. As a result, there turns up a problem of the degree of understanding and nature of events interpretation, which affects the behavior and worldview of a person. This problem is based on the media user's fear not to cope with decoding of the media text meanings, which were shaped in the semantic field when encoded by the creator. Conventionally, mass media is pragmatic in approaching the creation of media texts, introducing certain communicative effects, a kind of attention hooks, to engage the audience and hold them in their information space. But the very long-term fixation of attention is the main problem resulted from a communication barrier.

The same problem is extended to the educational process. Moreover, not only in terms of representing the quality of information in order to expand the student’s/learner’s worldview, which is due to his/her sensual-emotional outlook, but also in connection with the communicative effects included in the information, which usually orient people towards in-depth interaction with the world. As a rule, the character of both professional and individual reflection is associated either with an understanding and/or misunderstanding of what is happening, or with misunderstanding of the essence of specific processes at universal, general and some particular levels of human activity. At the same time, the learning of knowledge codes and immersion in them characterizes the degree of free reflection of an individual, his/her intellectual potential. As noted by the Russian historian Klyuchevsky (1990), “... an individual is free, as far as when understanding historical regularity, he contributes to its manifestation or, when misunderstanding, he complicates its action” (p. 344). In this context, the prevailing role of verbal information in the communication process is indisputable, especially when there is an increase in the impact of media content on the formation of professional and individual attitudes and positions. In this regard, the establishment of an algorithm for studying media texts in order to realize their impact on a consumer’s mind and view of life allows improving the communication link between the addressant and the addressee.

Research Questions

The study of the problem is devoted in general to encoding and decoding of media text meanings, but the main thing is to identify the algorithm of their interpretation by media users, which is a difficult task. Psycholinguistic and semiotic theories covered a wide range of issues and dealt mainly with information, text semantics and communicative effects perception (transmission of mental content to the addressee in order to get response), which was reflected in a number of works: from Ferdinand de Saussure in his notes on general linguistics to Umberto Eco concerning hyperreality in his excessive interpretations. However, in the digital period, semantic analysis became a trivial machine procedure, a lot of research in structural linguistics and psycholinguistics has been devoted to its study. Its main concepts are semantic space, semantic field, and semantic dominant (Lappin & Fox, 2015; Heine & Narrog, 2011). These concepts are to be clarified, since they have fundamental differences.

Media text semantic space is a semantic system, including language elements conditioned by the author’s intention and the reader’s interpretation (Mehler, Lücking, Banisch, Blanchard, & Job, 2016; Linzen, 2016). Semantic field is a train of words existing in a person’s memory that corresponds to a certain meaning of a concept, which represents the objective, conceptual or functional similarity of phenomena (Wangru, 2016; Zhukova & Petrochenko, 2017). At that, the "semantic field" concept refers only to words, whereas the "semantic space" concept reflects the relationship of all elements of the text. Semantic dominant is a semantic emphasis, which embodies the author's thought. When a user refers to the media text, he/she unrolls the model of semantic dominants rolled up by the author. Semantic dominants are defined as “semantic individually emphasized meanings” of words and sentences, which predetermine the understanding of the ideas expressed in the text by the author. (Lazutova, 2018: 3).

There was also developed the classification of communicative effects, proposed in 1976 by Ball-Rokeach and DeFleur (1976). The authors had identified three types: cognitive ones, through which ideas, values and attitudes are formed; affective ones, working on the emotional state and perception of social phenomena; behavioral ones, which activate or retard a particular type of activity. Thus, the communicative effect is the user's reaction to the message being received. The subject of communicative effects in the media text is the most discursive one (Campbell, Martin, & Fabos, 2015; Russell, 2018; Valkenburg, Peter, & Walther, 2016; Cacciatore, Scheufele, & Iyengar, 2016).

The development of approaches to study of complex relationships between media texts semantics and communicative effects resulted in the analysis of the meaning of “emotional intelligence” (Payne, 1985; Mayer, 2001; Oatley, 2004), that plays a significant role in life of modern man. In particular, “emotional intelligence” acts as a dominant idea when an affective (emotional) state arises at the moment of decoding the author's semantic space of a media text. And the main task of the study is to identify the algorithm of this phenomenon history.

Purpose of the Study

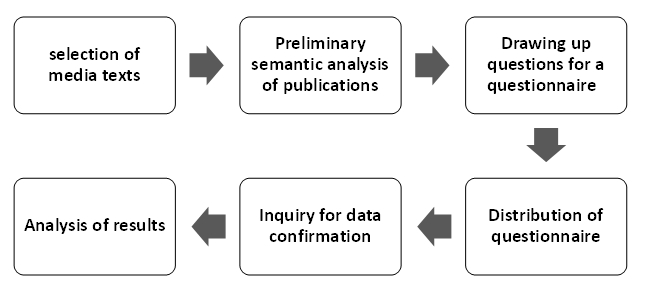

But how to recognize the degree of media text semantics perception by an individual? To solve this problem, it is advisable to turn to a questionnaire and consumer inquiry as an experimental model of using a media text semantic analysis. The model may be subdivided into the following stages of consequent actions: selection of media texts; preliminary semantic analysis of publications; drafting questions for a questionnaire; distribution of the questionnaire; conducting a survey to confirm the data; analysis of results. The procedure is shown as block diagram in Figure

However, the identification of the relationship between the semantics of the media text and the communicative effect requires a two-way consideration of this phenomenon. First of all, the semantic codes enclosed in the media text are considered, secondly, the meaning of senses perceived by a consumer, which can be interpreted depending on the intentions, abilities and extralinguistic experience of an individual. At the same time, the understanding of information by an individual becomes more complicated due to adding additional meanings to media text semantics that have arisen from his/her memorized ideas. In other words, when meeting with a media text, there takes place an ambivalent, considering the author's influence, perception of the event. But if the media text is about an event unknown to the media consumer, which does not correlate with his/her knowledge and experience, have no powerful contextual links in his/her mind, then the opinion about what happened is more identified with the position of the author of the publication. However, it is also possible to relate to media text without changing the structure of individual consciousness, when conceptual meanings are not transformed, the only changes will be in perception of the text meaning as a result of associative links with emotional images. Such is an attitude of the consumer that forms the general emotional mood, view of life (Glapka, 2017; Redman, 2018; Burroughs, 2017; Berger, 2018).

At the same time, the selection of media texts can be carried out according to a thematic, problem, genre or other principle, depending on the research tasks set. And in accordance with them, the experimenter analyzes the media text semantic space.

Research Methods

For reading media texts, a wide range of virtual and real users is selected, formed according to certain parameters of the focus group. In the first case, the survey is divided into a number of areas: for sociometric measurements, for collecting data on initial and subsequent emotional state of users, on understanding the content of the text and ensuring that the publication is read for the first time. It is required to get the clearest picture of the communicative emotional effect. In the second case, the questionnaire is focused on the user's sense and emotional state and understanding of the text.

To compare the meanings encoded by the author in the media text and decoded by the user, as well as to confirm the nature of the emotional effect, it is required to conduct an additional survey in a real or virtual environment. A set of questions is regulated, but spontaneous questions are allowed to clarify answers.

When studying the media text perception, it is required to consider that the integrity of a read media text idea is built by means of its “word-for-word” perception. There is no formulated approach that describes the perception of a media text as a unit of communication. Therefore, when analyzing the text, it is important to identify key words combinations (syntagmas) on which the decoding and understanding of the text is built. Theoretically, there is the problem of interpreting the text content, understanding its whole meaning and semantic structure by the user. In practice, this problem is solved with the help of keywords highlighting, the set of which is lined out according to responses of readers. The overall picture of the media text perception reflects the frequency of the words used, which define the conceptual core and the periphery. In the first case, this shows the unambiguity of the media text, in the second case - the variation of communication.

The text indexing using a set of keywords may include their small, medium, and large body. Small one (up to 5 words) reflects the media text topic or general concepts. Large one (up to 20 words) details the text subtopics. An average set of words (up to 10-12 words) is the most preferable, it refers to text displaying according to the author's vision. A set of keywords is detected using a questionnaire and confirmed by an inquiry. It demonstrates the emphasizes of the recipients' attention, that is, how they remember the main determinant ideas. A set of keywords is fixed in an individual's mind not only when they are repeated in the media text, presented in the headline, lead, beginning of paragraphs or as part of special lexical structures, but also in synonymous substitution and in presence of a non-expressed formally semantic relationship. Such data correct the assumptions about the correct or incorrect understanding of the text when it is perceived (Karl, Wisnowski, & Rushing, 2015; Onan, Korukoğlu, & Bulut, 2016; Martí-Parreño, Méndez-Ibáñez, & Alonso-Arroyo, 2016; Salloum, Al-Emran, Monem, & Shaalan, 2018).

Preliminary semantic analysis of the media text is necessary for researchers to determine the structure and predict what elements will affect the text perception and the reader's emotional reaction. In order to imagine the basis for his/her emotional decision, it is required to identify the structural units that concentrate his/her attention: as a rule, these are verbs and nouns, less often adjectives and adverbs (Popova & Sternin, 2007; Talmy, 2000). It is worth to rely on verbs, as they characterize the process of development of events presented in the text.

Findings

Semantic analysis of publications is based on the determination of semantic fields for the main semantic elements. A semantic field is formed from a lot of word meanings. It is impossible to predict the reader's mental image when perceiving any word; therefore, the semantic field is built using a synonymous chain, the sequence of which is determined by the frequency of use. In this regard, it is sufficient to use any dictionary of synonyms indicating such a frequency. Thus, in the semantic analysis of materials, it is advisable first to isolate the semantic dominants, and then build semantic fields to their elements with ambiguous meaning.

The survey of recipients is the main sociological method of collecting empirical information. The participants are asked questions, their answers are recorded. The list of questions is compiled in a certain sequence. Depending on the study objectives, questionnaires may be formalized, containing "closed" questions with ready-made answers, or a controlled-association scale; semi-formalized, consisting of both "closed" questions and "semi-closed" with a free answer as per recipient's choice; low formalized, containing "open" questions, with no answers, and implying an arbitrary response from the recipient; not formalized, containing the topics discussed. The survey may be carried out as an interview (interview form) or by filling out a questionnaire (questionnaire form).

It is advisable to use a mixed type questionnaire: with "closed", "semi-closed" and "open" questions. "Closed" questions are relevant for collecting general information about media consumers. "Semi-closed" questions are appropriate if the recipient does not understand the question, or is ready to comment. "Open" questions are indispensable for sections where the work with media text is planned, so that the recipients can describe their understanding and attitude to the content of the information, write out keywords, add comments. The questionnaire structure is based on a) general questions about the type of activity, level of education, age of consumers; b) special questions about which news and from which media resources the user prefers; c) media text and questions about its content (there may be several texts). To analyze the observance of the "novelty of perception" principle, it is advisable to provide the questions to the media text with an item on whether the survey participants are familiar with news in publication and weather they have additional information on this topic. Initial familiarization with the media text minimizes distortions when decoding author's meanings in the material.

When implementing educational goals, during survey it is advisable to focus on media texts with problems (inconsistency of composition, logical incoherence, stylistic errors, other obvious errors in judgements) and such media products that do not meet the journalistic norm (lack of objectivity, excessive emotionality, informative scarcity, others).

A motive, which correlates to the user’s interest to the informational content, is critical in considering the nature of perception. Therefore, media texts submitted for the survey should be of a universally significant, political or social subject matter. But in order to ascertain whether the media texts chosen for the survey coincide with the preferences of the recipients, the questionnaire regarding the preferred topics of news events is introduced into the questionnaire.

Conclusion

The conduct of such study is possible in a face-to-face and virtual form. To improve relevance, the survey is conducted in parallel, but the composition of the reference group is selected in advance. The correctness of the result analysis largely depends on the initial semantic analysis of the media text, and clear recording of decoded semantic elements. The peculiarities of the procedure are also taken into account. First, significant parts of the media text are selected, where the reduction of both subordinate parts of sentences and whole phrases of an explanatory nature is permissible. Since the title complex (title and subtitle) serves as a reference point in relation to the idea of the text, while the lead introduces into the topic or denotes the formulation of the problem, special attention is paid to them: key syntagmas, which are the semantic dominant, are distinguished. The semantic field of the media text is built on the syntagmas. It is advisable to determine and compare the semantic dominants of the local level (paragraph), total (composite parts, chapters) and universal (entire text) levels.

Before the survey it is necessary to identify the hypothetical range of emotional states of the recipient - before and after reading the media text. The presence in the questionnaire of a carefully thought-out scale of questions about the positive and negative nuances of the cognitive state will help to determine the shades of the emotional state of the survey participants and degree of their intensity. The purpose of the selection of keywords in the survey should be clear to the recipients, correlating in their minds with decoding the meanings of the media text, and not with rechecking their intellectual abilities. The survey interview clarifies the semantic dominants decoded by the media consumer, so that a comparative analysis can reveal the degree of their displacement at the time of the emotional and communicative effect and determine whether the emotional intelligence is a supporting tool in determining the content of news events, or, on the contrary, acts as an obstacle or even becomes a barrier in the perception of the representation of the event picture of the world.

References

- Ball-Rokeach, S.J., & DeFleur, M.L. (1976). A Dependency Model of Mass-Media Effects. Communication Research, 3(1), 3-21. DOI:

- Berger, A.A. (2018). Perspectives on Everyday Life. Cham: Palgrave Pivot. DOI:

- Burroughs, B. (2017). Streaming Tactics. Platform: Journal of Media & Communication, 8(1), 56-71.

- Cacciatore, M.A., Scheufele, D.A., & Iyengar, S. (2016). The end of framing as we know it… and the future of media effects. Mass Communication and Society, 19(1), 7-23. DOI:

- Campbell, R., Martin, C., & Fabos, B. (2015). Media Essentials: A Brief Introduction. Bedford: St. Martin's.

- Glapka, E. (2017). On a stepping-stone to cultural intelligence: Textual discursive analyses of media reception in cultural studies. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 20(1), 31-47. DOI:

- Heine, B., & Narrog, H. (Eds.) (2011). The Oxford Handbook of Grammaticalization. New York: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Karl, A., Wisnowski, J., & Rushing W.H. (2015). A practical guide to text mining with topic extraction. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics, 7(5), 326-340. DOI:

- Klyuchevsky, V.O. (1990). Sochineniya. V 9 t. [Writings In 9 v.]. T. IX. M.: Izd-vo «Mysl'». [in Rus.].

- Lappin, S., & Fox, C. (2015). The Handbook of Contemporary Semantic Theory. New York: Wiley.

- Lazutova, N.M. (2018). Problema smyslovoj dominanty v semanticheskom pole teksta [The problem of semantic dominant in the semantic field of the text] YAzyk i rech' v Internete: lichnost', obshchestvo, kommunikaciya, kul'tura. Moscow: RUDN University [in Rus.].

- Linzen, T. (2016). Issues in evaluating semantic spaces using word analogies. In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Evaluating Vector-Space Representations for NLP (pp. 13-18). DOI:

- Martí-Parreño, J., Méndez-Ibáñez, E., & Alonso-Arroyo, A. (2016). The use of gamification in education: a bibliometric and text mining analysis. Journal of computer assisted learning, 32(6), 663-676. DOI:

- Mayer, J.D. (2001). Emotion, intelligence, and emotional intelligence. In J. P. Forgas (Ed.), Handbook of affect and social cognition (pp. 410-431). Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Mehler, A., Lücking, A., Banisch, S., Blanchard, P., & Job, B. (Eds.) (2016). Towards a Theoretical Framework for Analyzing Complex Linguistic Networks. Berlin: Springer.

- Oatley, K. (2004). Emotional intelligence and the intelligence of emotions. Psychological Inquiry, 15(3), 216-221.

- Onan, A., Korukoğlu, S., & Bulut, H. (2016). Ensemble of keyword extraction methods and classifiers in text classification. Expert Systems with Applications, 57, 232-247. DOI:

- Payne, W. (1985). A Study of Emotion: Developing Emotional Intelligence; Self-Integration; Relating to Fear, Pain and Desire (Doctoral Dissertation). Cincinnati, OH: The Union for Experimenting Colleges and Universities.

- Popova, Z.D., & Sternin, I.A. (2007). Semantiko-kognitivnyj analiz yazyka [Semantic-cognitive analysis of the language]. Voronezh: Istoki [in Rus.].

- Redman, L. (2018). Probes’ Review Decoding Symbols and Making-Meaning with Others. In Knowing with New Media (pp. 243-262). Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan. DOI:

- Russell, N. (2018). The Paradox of the Paradigm: An Important Gap in Media Effects Research. Journal of Communication, 68(2), 369-379. DOI:

- Salloum, S.A., Al-Emran, M., Monem, A.A., & Shaalan, K. (2018). Using Text Mining Techniques for Extracting Information from Research Articles. Intelligent Natural Language Processing: Trends and Applications. Studies in Computational Intelligence, 740, 373-397. DOI:

- Talmy, L. (2000). Toward a Cognitive Semantics, Volume 2. Typology and Process in Concept Structuring. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Urazova, S.L. (2015). Mediakommunikacii v fokuse cifrovyh transformacij [Media Communications in the Focus of Digital Transformations]. MediaAlmanac, 6(71), 21-29 [in Rus.].

- Valkenburg, P.M., Peter, J. & Walther, J.B. (2016). Media effects: Theory and research. Annual review of psychology, 67, 315-338. DOI:

- Wangru, C. (2016). Vocabulary Teaching Based on Semantic-Field. Journal of Education and Learning, 5(3), 64-71.

- Zhukova, N.S., & Petrochenko, L.A. (2017). The Functional-Semantic Field of the Mental Deviation Subcategory as a Euphemistic Phenomenon. In International Conference on Linguistic and Cultural Studies (pp. 250-259). Cham: Springer.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

30 September 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-068-6

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

69

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1054

Subjects

Education, educational equipment, educational technology, computer-aided learning (CAL), Study skills, learning skills, ICT

Cite this article as:

Urazova, S. L., Lazutova, N. M., Volkova*, I. I., Algavi, L. O., & Delfino, D. A. (2019). Semantic Space And Algorithm Of Media Text`S Consumption In Digital Space. In S. K. Lo (Ed.), Education Environment for the Information Age, vol 69. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 948-956). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.09.02.106