Abstract

Recently, the Romanian Ministry of Education has decided to promote mandatory courses on academic ethics and deontology in all Romanian universities (both at the Bachelor, and Master's level), a move which has its origins in some very public scandals concerning doubtful academic moral values (mostly plagiarism in doctoral dissertations, usually involving political actors). While this initiative seems creditable, we lack at this moment data concerning the current ethical values of students, in order to evaluate, after some time, the effects of such courses on the overall ethical status of Romanian universities. Thus, like in some other cases of educational policies, this endeavour could end in a mere formal and bureaucratic procedure. Therefore, this paper aims to be a simple investigation on the opinions and statements of Romanian students regarding some ethical issues such as plagiarism and cheating in exams, in a double perspective: one concerning the perception of each student’s moral values, and another one concerning what she/he feels are the values of her/his peers. The results we provide point to a somehow surprising conclusion: while nobody denies that cheating and plagiarism take place in our schools and universities, it seems that the culprits are – every time – all around us, except us, of course; We must conclude that we need strong mechanisms to take plagiarism and cheating out of the shadow of denial at a personal level.

Keywords: Ethicsplagiarismcheatingstudents

Introduction

A common definition of academic integrity states that it is “the commitment, even in the face of adversity, to six fundamental values: honesty, trust, fairness, respect, responsibility, and courage. From these values flow principles of behaviour that enable academic communities to translate ideals to action” (ICAI, 2013). The antonym of academic integrity is “academic dishonesty” (McCabe & Trevino, 1993) (with variants such as “academic fraud” or “academic misconduct”), concepts that refer to one or more behaviours (or even a complete set of behaviours – an entire way of being) which stands against the moral values proposed or imposed by an educational institution. Despite the beliefs of some recent studies, academic misconduct is not a new phenomenon but as old the first forms of evaluation. Cheating in tests, for example, was such a major issue in Ancient China, thousands of years ago, that the death penalty had to imposed (for both the examinee and the examiner) if such an event took place (Lang, 2013).

Several categorizations or classifications of academic dishonesty have been attempted, but most of them tend to underline the same phenomena. Usually, studies mention behaviours such as: copying from “illegal” sources during tests (crib notes, books hidden in various places, other colleagues’ papers, outside sources like telephones, radios etc.), bribing the examiner (under various forms, from money or goods to influence or even symbolic rewards – this is one the very few form of academic dishonesty sanctioned by the penal law), lying the examiner/evaluator in any form in order to gain any kind of advantage (from lying in order to get an extension of the deadline for turning in a paper, for example, to lying about medical conditions or tragic events in order to “soften” the evaluator’s attitude), copying fragments from various sources without giving the necessary credit (all forms of plagiarism), buying or obtaining in other ways works written by other people and turning them in as one’s own work, having other people taking tests instead of the student etc. Obviously, this list can be extended a great deal by detailing contexts and circumstances for all of the behaviours noted here, but this is not my purpose here (see, for instance, the detailed description of academic dishonesty in Ercegovac & Richardson, 2004). I suggest that unless the researcher intends to do a radiography of the ways in which students are dishonest, he/she should use a limited list of dishonest behaviours in order to keep people concentrated on the key facts. In my case, I prefer to guide myself on the following reasoning:

significant dishonesty can occur only in evaluation contexts;

evaluations can be basically divided in two major categories: evaluating recorded/learned knowledge (all forms of tests, either written or oral) or evaluating (usually) cognitive abilities (all forms of students’ oral or written own compositions such as essays, dissertations etc.)

students’ dishonesty is adapted to these two contexts of evaluation.

Drawing from this (and from my own experience as a teacher), I have come to be preoccupied by two major instances of academic misconduct: cheating (in tests) and plagiarism (in all its forms). Other researchers have noted the same thing before; MacFarlane, Zhang, and Pun (2014) asserted that the term “academic integrity” has come to refer almost exclusively to behaviours such as plagiarism and cheating.

Problem Statement

At this moment, despite some recent efforts in researching academic dishonesty, we have little (or none at all) reliable data concerning the psychological mechanisms involved in cheating and/or plagiarizing, the profile of the cheater/plagiarizer and the most efficient ways to inhibit or prevent such behaviours. Since these subjects involve much aspects of the human development (from the moral development in the early stages of life, to school training and general policies of the educational system, for example, in addition to cognitive or personality traits), it is obvious that we cannot hope to discover a “special something” which would fully resolve or explain what we are enquiring.

Plagiarism.

In the last decade, the Romanian public scene has witnessed a tremendous increase of the interest for the matter of academic ethics, and in particular for the subject of plagiarism. As one could expect, this increased concern is not the result of a systemic and natural transformation of the population’s intellectual preoccupations, but instead a more mundane pursuit of the political game. Like in many other European countries, some of the important political actors had their intellectual achievements contested either by political opponents or by members of the civil society mainly by unveiling possible plagiarisms, a thing which happened in the last decade (maybe a bit more) in Germany, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Croatia, Russia etc. The first direct result of such public scandals was, in most cases, the resignation of the ones accused of academic misbehaviour, even though, in most cases involving politicians, they were not practicing specific occupations in which their competences could have been questioned (because of the plagiarism) but, instead, their reputation and moral profile was now being questioned (a fact which is usually fatal for political figures). The secondary result of such scandals was a major increase of the public in what it concerns the rules, regulation and customs of academia (and more specific, the ethics of research and academic integrity), a thing which happened in Germany (following the plagiarism scandal involving Germany’s Minister of Defence, Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg), Hungary (the President of Hungary Pál Schmitt) or Romania, (Romania’s Prime-Minister, Victor Ponta), all of which were accused of plagiarism in their Ph.D. papers. The most important benefit of all these public scandals involving political figures is the fact that the large public becomes increasingly aware of the matter of academic integrity and, thus, we can drastically improve our chances for a lifelong and reliable education in this direction for the next generations. At the same time, because politics is an inherently subjective field and tends to cause passional reactions from people, it becomes very difficult to perform researches on the public perception of this topic since people’s opinion will be, obviously, affected by their political stance and the way the subject affects their favourite political party/figure.

In the particular case of Romania, our system of education is not necessarily accustomed to evaluating the students’ independent/creative work. The whole idea of giving written assignments to be carried out at home became common only after the beginning of this century and came to be prevalent in high schools (and universities) in the second decade of the century. As teachers were not particularly prepared for this, students learned rather quick that you can turn in any kind of material, copied in its entirety or just in small passages from other sources, with the teachers being unable or unwilling to test the accurateness of the citation system. More than this, in the vast majority of the classes, students were not instructed on how to cite other works, how to use the Internet for documentation or – put in simpler words – how and why to be moral in performing academic tasks. Unfortunately, this passive approach on students’ work was perpetuated at the universities’ level, a phenomenon facilitated by the rapid and significant increase of the students’ number in the previous decade (especially around 2010, when more than 400,000 students were enrolled in online forms of higher education, forms which favoured evaluation through creation works). At this moment, we have little data concerning the rates of plagiarism within the student population of Romania (and almost no reliable data on the reasons and the psychological mechanisms involved in cheating and/or plagiarizing). One of the few comprehensive studies on this topic (Foltýnek & Glendinning, 2015) shows that Romania is ranked 4th in Europe by the rates of plagiarism (over 50% of the Romanian respondents believed that they might have plagiarised accidentally or deliberately at least once). Other sources (www.plag.fr) state that Romania leads the ranks of plagiarism in Europe with an over 26% plagiarism rate.

Cheating in exams and tests

As opposed to plagiarism, cheating in exams leaves no traces (to speak in forensic terms) which means that if one did not get caught while doing it, it is extremely improbable to be accused at a later time. The first level of measures taken against all forms of cheating targets not the prevention through education against this, but rather making classrooms (or online environments) less cheating-friendly and making the teachers more attentive to contemporary means of cheating. For example, the Romanian equivalent of the SATs, the national Baccalaureate exam, take place in extremely rigorously controlled environments since 2011 (more precisely, video cameras have been installed in every classroom in which exams take place and the video footage is being monitored in real time, but also in replay). The first major and visible result of this was the fact that the passing rates for the exam (the percentage of students who passed the general exam, from the total number of students enrolled for it) dropped abruptly (as shown in the graph below). Of course, questions can be asked about how the percentage managed to rise up again in the following years (though they never reached 80% like before 2011), but the discussion is not simple and it entails even political details. In a previous work (Patroc, 2018), I have treated the subject of cheating in tests extensively, but only referring myself to online testing; there, I have argued – based on some facts and figures – that every new generation of students is more prone to cheating than the previous ones.

Unlike plagiarism, where evidence of the dishonesty remains and can be retrieved and analysed even after decades, we have no compelling data on cheating in exams and tests since it happens “live” and as soon as the exam is over, the student is virtually exonerated of any kind of charges against him/her. In this instance, we can solely rely on the testimony of the cheaters, but – for obvious reasons – we must consider the responses we get with much caution.

Research Questions

Since at this moment we have basically no data on the mechanisms and demographics of academic dishonesty for Romanian students, we will be content with any kind of preliminary findings on this topic. As a consequence, the questions we ask are general and do entail strict hypotheses: What do students think about the rates of cheating and plagiarism in Romania? How do they compare themselves to their peers when discussing these aspects? Are there differences between the undergraduate education and the higher education regarding plagiarism and cheating?

Purpose of the Study

This study aims to find and interpret some preliminary data concerning the rates of cheating and plagiarism in Romanian students and their opinions regarding the mechanisms involved in cheating and the possible measures that can be taken in order to inhibit academic dishonesty.

Research Methods

The data was collected through a questionnaire addressed to current students and containing questions related to the subject of cheating in tests, both in high school and university, and plagiarism (as well for high school and university). The questions targeted the personal experience of the students (“How often did you plagiarize when you were a high school student?”), but also their perception of how severe this phenomenon was (“To your knowledge, how often did your colleagues plagiarized during high school?”). Most questions required answers on a Likert scale with 10 steps. Between April 2018 and July 2018, 565 students provided answers for this research, most of them being students at various programs within the University of Oradea, in Western Romania. Most of them are students in the field of Educational Sciences (52.5 %), Psychology (28.3%), and Philology (14.7%), while the rest of participants come from various fields such as History, Geography, Sports. Related to properties of the sample, let us mention the fact that the respondent’s group could have been larger and it could have included students in other fields – such as engineering or medical studies. There is an obvious disproportion between the number of female respondents vs. male respondents (74.3% female vs. 25.7% male.

Findings

Cheating

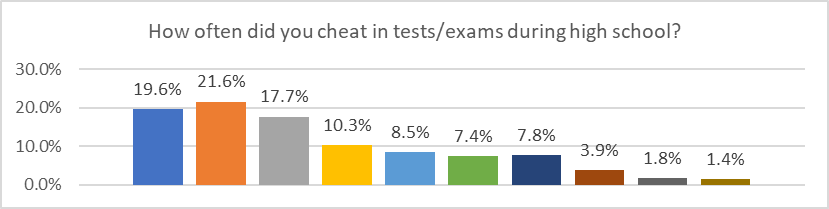

The first data we look at is the students’ confession on how much they resorted to cheating during their high school. As the chart below shows us, there is an obvious tendency for the students to see themselves as rather fair individuals, which followed the moral code expected from a normal student. The psychological limit seems to be drawn somewhere between the 3 and 4 values for answers (figure

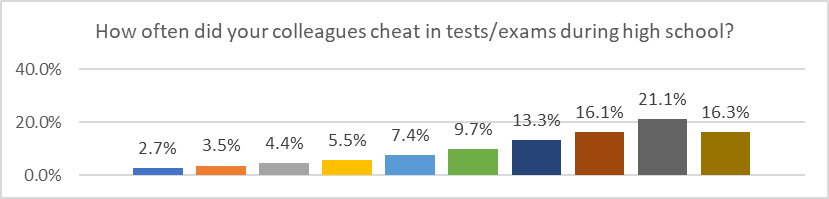

When targeting the same question at the respondent’s peers, there is an overwhelming consensus on the fact that – if cheating happened – it was done by the others (more than 66% of the answers are situated in the 7-10 interval of evaluation, which is similar to a rather bleak perspective on the status of cheating in the respondents’ classes in high school) (figure

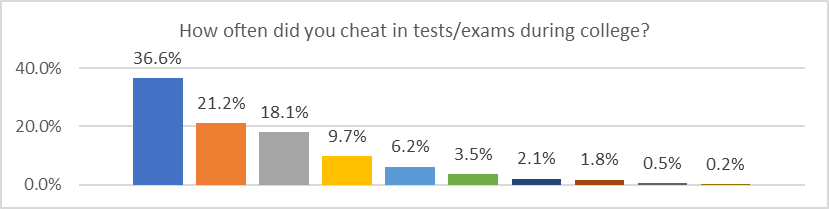

When asking the same question, but this time about college (the current level of studies for our respondents) we notice a more powerful polarization tendency, which can only be explained through the fact that students provided extremely desired (in their opinion) answers. Less than 10 students evaluated their cheating with scores between 8 and 10, while more than 75% of them claimed to have avoided cheating almost completely (scores between 1 and 3). A staggering close to 40% maintained that they have absolutely never cheated during their college years. (figure

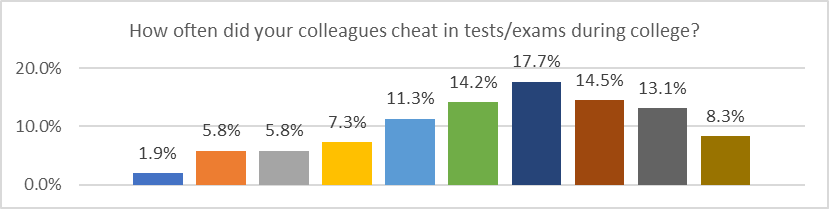

As mentioned above, the responses to the same questions, but directed towards the respondents’ peers, are proofs not only for the fact that they were rather dishonest, but also to the fact that they tend to keep their self-esteem at high levels, while blaming others for the bad things which happen around us. This time, the majority of the responses are situated between the 6-9 interval (with the peak value being 7), which can be explained by the fact that the self-esteem of the respondent is somehow dependant on the overall status of the group in which they are a part (figure

Plagiarism

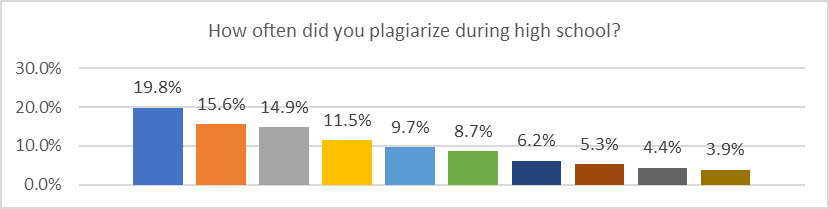

At all surprising, the data concerning plagiarism done by students is remarkably the same with the data on cheating (figure

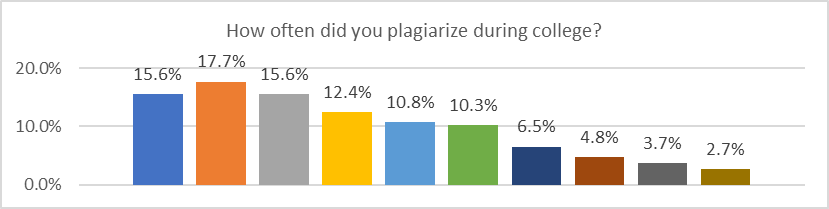

At the college level, things look extremely similar to the reports on cheating, with a small peculiarity: the peak value was “2” instead of “1”, while the general tendency was to have smaller gaps between answers, a fact which could be easily explained by the fact that in the daily experience with teachers, plagiarism is less frowned upon than cheating, at least at the bachelor’s level (one could argue that there is a silent complicity between students and teachers regarding this aspect) (figure

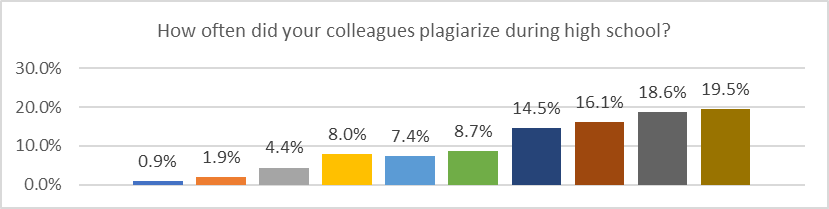

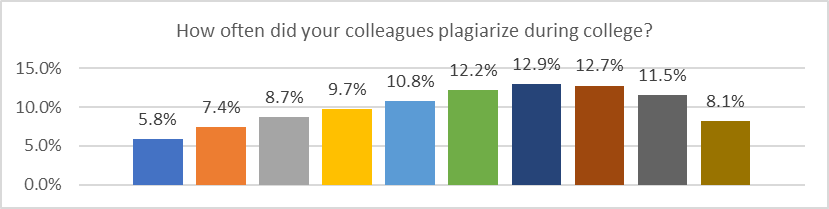

As expected, our subjects tend to believe that their peers plagiarize more than themselves, and we can observe the same tendency to maintain high levels of self-esteem by creating less than drastic evaluations of their groups. Also, as a result of the fact that plagiarism is not very much explained to and understood by students, the results tend to be spread on closer intervals than in the case of the other answers (figure

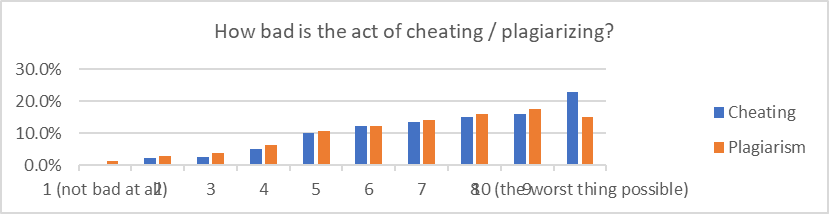

Since one of the questions addressed to students aimed specifically their evaluation on how bad (how immoral) are the acts of plagiarism and cheating, let us compare the results. As visible from the figure

Conclusion

The most important conclusion of this study is one related to the methodology of research; we conclude that students are most likely insincere when answering questions related to cheating and plagiarism in academic environments. Thus, we would need to rely not on their opinions, but rather on observation and objective data in order to accurately asses the rates of cheating and plagiarism in higher education institutions. Next to this, we can conclude as well that there is an obvious and extremely generalized tendency in students to see (or to report) themselves as extremely virtuous when compared to their peers. They tend not to deny the existence of phenomena like cheating and plagiarism, but they tend to completely dissociate themselves from it. Also, the rates of blaming the peers seem to decrease when we are talking about current peers (as opposed to former peers). What seems to be a bit surprising is the fact that the answers provided tend to be extremely categorical: “

References

- Ercegovac, Z. & Richardson, J. (2004). Academic Dishonesty, Plagiarism Included, in the Digital Age: A Literature Review, College & Research Libraries, 65(4), 301-318.

- Foltýnek, T. & Glendinning, I. (2015). Impact of Policies for Plagiarism in Higher Education Across Europe: Results of the Project. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis, 63(1), 207-216.

- International Center for Academic Integrity (ICAI) (2013). Fundamental Values of Academic Integrity (2nd Edition). Retrieved from http://www.academicintegrity.org/icai/assets/Revised_FV_2014.pdf

- Lang, J.M. (2013). Cheating Lessons: Learning from Academic Dishonesty. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- MacFarlane, B., Zhang, J., & Pun, A. (2014). Academic integrity: A review of the literature. Studies in Higher Education, 39(2), 339–358.

- McCabe, D., & Trevino, L. (1993). Academic Dishonesty: Honor Codes and Other Contextual Influences. The Journal of Higher Education, 64(5), 522-538.

- McCabe, D. L. (2016). Cheating and honor: Lessons from a long-term research project. In T. Bretag (Ed.), Handbook of academic integrity. Singapore: Springer.

- Patroc, D. (2018). Arguments Against Online Learning. In C. Fitzgerald, S. Laurian-Fitzgerald, & C. Popa (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Student-Centered Strategies in Online Adult Learning Environments (pp. 120-138). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

15 August 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-066-2

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

67

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2235

Subjects

Educational strategies,teacher education, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Pătroc *, D. (2019). The Ethical Values Of Romanian Students. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 67. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 746-754). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.08.03.89