Abstract

Employees' satisfaction at work becomes a focal point in research and in organizational psychology discussions because, as studies show, it has a great impact on performance. We assumed that: there is a significantly positive correlation between the level of work addiction and the work commitment and that there is a significantly negative correlation between the level of work addiction and the couple satisfaction (a high level of workaholism - involves a low level of satisfaction in couple). In our research, we investigated 70 participants, 35 male participants and 35 female participants aged between 21 and 48 years (average = 30.54 years old), the level of studies being average and high (23 participants have average education and 47 participants have higher education). The tools we used for the current study are: Work Addiction Risk Test – WART, The Couple satisfaction scale (Dyadic Adjustment Scale), The work engagement scale Scala (Utrecht Work Engagement Scale – UWES).The research results showed that the scores at the workaholism variable are associated with scores at the work commitment variable and we obtained a correlation coefficient r = 0.429, at 99% confidence level, p> 0.01). Also, the results showed that there is a significantly negative correlation between the level of work addiction and the couple satisfaction (a high level of work addiction - involves a low level of satisfaction in the couple), the correlation is negative at a level of r = -0.285, significant at a level of 0.05.

Keywords: Workaholismcouple satisfactionaddictionperformance

1. Introduction

Work satisfaction refers to those positive attitudes or emotional dispositions that people can get through work. Employee satisfaction at work becomes a focal point in research and in organizational psychology discussions because, as studies show, it has a great impact on performance. There are two types of work satisfaction in relation to employees’ feelings:

global satisfaction that relates to employees' feelings about their workplace. (I like my job) (Mueller & Kim, 2008).

specific satisfaction that relates to feelings about salary, program, benefits, hierarchy, professional development opportunities, working environment, quality of relationships with colleagues, etc.

An individual can have a well-paid job and not be satisfied because it is boring and a lack of the right incentive. In fact, a poorly paid job may be more satisfactory if it is provocative and stimulating enough. There are many factors that need to be taken into account when determining how satisfied an employee is with the workplace and it is not always easy to determine the most important factors for each employee.

Job satisfaction is very subjective for each employee. It is difficult to establish all the antecedents that lead to job satisfaction. However, an important dimension that positively correlates with satisfaction is engagement or dedication. For example, some organizational cultures and workplace structures may be more appropriate or desirable for work-related types (Porter, 1996), or some of the aspects of workrelated dependency may even be taught by some employees through training. Work-dependents (workaholics) have been described as critical, inefficient, unfit to be delegated, difficult (Machlowitz, 1980).

Essentially, commitment to work captures how employees experience their work: stimulating and energetic, or as a thing to which they devote their time and effort (the component of vigor); as a search for meaning (dedication); as something exciting and on which it is concentrated (absorption).

Before defining a "working" person, it is appropriate to consider that such behavior, in which labor is the central element, can have two sides, as follows:

a positive side, when the person is dedicated to the work he/she performs because he/she considers it interesting and corresponds to the internal standards and values (the organizational commitment);

a negative side, when work is associated with an obligation of doing, more often, more than necessary and it is felt as a compulsion (workaholism).

Research by Klaft & Kleiner, (1988) have shown that work-related dependents with leadership positions are not efficient because they have unrealistic performance standards, which can lead to employee frustration, interpersonal conflicts at work, and low employee morale.

Other psychologists have emphasized the crucial role that supervisors and managers have in supporting those who tend to work addiction (Evans & Bartolomé, 1984). For example, setting priorities, setting breaks and closing hours of the work program could be assisted by managers.

Barling & Macewen (1994), on a sample of 134 practitioners of medicine and their wives, observed two components of A-type behavior identified among a study on the lack of marital satisfaction. These components are: desire for success and lack of patience or irritability.

The lack of patience and the presence of the irritability of the spouses were associated with the lack of marital satisfaction from both husbands and wives, while the desire for success did not correlate with them. Robinson and colleagues (1995, 2001) consider labor addiction to be a symptom of a family sick system. Work dependence, like any other addiction, is for them, intergenerational, and is passed on from generation to generation through family processes and dynamics. Although not directly tested (work-related dependency on parents was not examined in relation to children), Robinson and colleagues found health-related symptoms both in work-dependent parents and in children (anxiety, depression).

(Robinson & Post, 1995).

In one of the few studies that examined the impact of work addiction on children, it was demonstrated that depression scores were significantly higher among children with at least one dependent parent. In a series of studies, work addiction is associated with the satisfaction of low relationships with friends, family and community (Burke, 1999), and associates with a weak balance of life work and family (Burke, 2000).

However, the relationship between work dependency and family or relational difficulties is not a clear or always observed relationship. Burke (2000) reported how married and divorced managers had behaviors and similar degrees of work addiction. In a more direct study, McMillan, O'Driscoll, and Brady (2004) found that both addicts and non-addicts had satisfactory results in terms of relationships.

A recent investigation on women has revealed that workaholism has a negative impact on family cohesion (Robinson & Chase, 2001), being considered as a family problem that stems from - and is maintained by - the unhealthy dynamics of family life (McMillan, O'Driscoll, & Brady, 2004).

Empirical research has concluded that work addiction adversely affects family life and will lead to conflicts. The issue of labor-related conflicts (or imbalances) has received increased attention in recent years (Frone, Russell, & Barnes, 1996; Hammer, Bauer, & Grandey, 2003). One reason for this interest is the widespread belief that events (both positive and negative) occurring in the workplace or outside the workplace are mutually affecting each other and it is very common. However, the major interest has been and is mostly about the impact of labor-related conflicts and their negative outcomes.

For example, studies have shown how work-related conflicts are significantly associated with psychological stress indicators and diminished physical health (Frone, Russell, & Barnes, 1996). Indeed, a 4-year longitudinal investigation found work-related conflicts as being significantly associated with depressive episodes, poor health and high alcohol consumption.

Given the above results, organizations have developed programs (flexible work schedules) to assist in the complexity of work and life balance. In any case, these efforts have shown modest and even inconsistent effects. Bonebright, Clay, and Ankenmann (2000), relying on the responses of 503 employees, found that both enthusiastic and non-enthusiastic addicts have higher scores in family conflicts in comparison to those who are not addicted to work. Furthermore, Robinson, Carroll, and Flowers (2001) reported that the wives of labor addicts believed that the relations with their husbands had more problems and that they felt less positive attitudes towards the latter.

Only a few studies have examined the consequences of work dependence on the quality of relationships, and those studies have relied solely on a single source of information (self-reports of employees or their partners). For example, Robinson and Post (1995) found that work addicts are more inclined to perceive families as having communication problems, more unclear roles and less involvement than those with less dependence on work. Robinson, Flowers, and Carroll (2001) reported that work addicts show a kind of loss of emotional attachment, care and desire, low positive feelings towards the partner, low physical attractiveness compared to those who are not addicted to work.

Congruent with these outcomes, Burke (1999) reported that work addicts have far lower scores in terms of family satisfaction than those with a different style of work (enthusiastic, uninhibited, relaxed, etc.)

2. Problem Statement

Workaholism involves a minimal intimacy with the life partner, a fear of intimacy and an escape from it because professional activity is perceived as a substitute for all other relationships. There is an emotional irritability to workaholics, but not a reduced intimacy, which can lead to the conclusion that these correlations cannot be absolutized and cannot lead to the generation of only one conclusion. The conflict between work and family was analyzed from the perspective of role-related stress, being considered a form of inter-conflict in which the roles associated with work and family are considered incompatible. Numerous studies have linked role-related stressors in general and role conflict, in particular, with a variety of work-related attitudes. Research has suggested that the conflicting relationship between work and family can lead to unfavorable attitudes towards work, such as dissatisfaction with work, or increased intentions to leave the organization or even actual leaving it.

3. Research Questions

The evaluation of the characteristics of family life dynamics and the assessment of the level of commitment to work;

The study of statistical differences on the risk of work addiction and commitment to work.

4. Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the study is the assessment of the characteristics of family life dynamics and the assessment of the level of work commitment as well as studying statistical differences regarding the risk of workaholism and work commitment. In this paper we analyzed the link between the level of work addiction and work commitment

5. Research Methods

Work Addiction Risk Test – WART Robinson, 1995

Dyadic Adjustment Scale – Spanier, 1989

Utrecht Work Engagement Scale – UWES, Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004

6. Findings

6.1.The verification of hypothesis number 1 – There is a significant positive correlation between

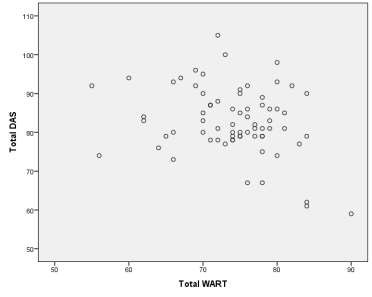

Using the Pearson correlation method, we analyzed the link between the level of work addiction and work commitment. The correlation is positive, significant and of medium level (r = 0.429, at 99% confidence level, p> 0.01). The scores for the work addiction variable are positively associated with the scores for the work commitment variable. The results show that the hypothesis is confirmed (Table

Work commitment and work dependency are two active, work-related states that are indicative of over-employment (Reanu Iftime, 2016). However, while commitment to work generally combines a great effort with positive effects and has beneficial consequences, labor dependency usually combines a great effort with a negative impact. Commitment to work is often defined as a positive, fulfilling state, a state of mind related to work that is characterized by force, dedication and absorption. Employees that are more intensely involved at work, are happy and absorbed in those activities, and resemble a lot to the work addicts. However, in contrast to the latter, the involved employees work hard either because they like it or because of external factors such as financial reward, career prospects, etc., and not because they feel an inner impulse that they cannot resist. Hence, on the one hand there is a "harmonious passion," when the individual is in control of his/her activity and feels rewarded and satisfied with his/her work. On the other hand, there is also "obsessive passion" when an individual is controlled by his/her work and he/she only thinks of avoiding guilt and frustration or other negative emotions.

0.05 (Table

Considering the obtained result, this hypothesis is confirmed, there is a negative correlation between the level of work addiction and family satisfaction. In this case, people who are accustomed to spend a lot of time at work are at the risk of being away from the family, of having low involvement, having the other member feel neglected, ma

While the data collected by Robinson and Chase (2001) supported the idea that workaholism undermines family stability, further research and longitudinal studies are required to document the degree of change or stability of workaholics beyond the professional career (Naughton, 1987). Specifically, it should be investigated whether deficient marital cohesion favors workaholism rather than the reverse (Robinson & Chase, 2001). In fact, Burke (1999, 2000) found that work addiction was not correlated with divorce, but with less satisfaction in family life, friendly relations, and community life.

7. Conclusion

In line with what has been discussed so far, formal counseling has been proposed for work addicts, especially if their tendencies can be associated with type A personality or with obsessive-compulsive traits. As Naughton (1987) asserted, a goal of therapy with work addicts that have compulsive tendencies is to reduce those behaviors up to a functional level for themselves as well as for the organization. (p. 185). Schaef and Fassel (1998) developed a 12-step program to reduce the addictive behavior both at an individual and organizational level. Also, in counseling of this category it was proposed the involvement of family members (e.g., Burke, 2000) because family support is considered crucial for the success of therapeutic interventions (Evans & Bartolomé, 1984). Finally, the use of training programs has also been suggested in order to assist work addicts in developing diverse interests that involve them in activities unrelated to work (Naughton, 1987).

Although this suggestion might be effective, it is critical for organizations to consider the negative implications of work dependence seriously before initiating or implementing any strategy or intervention. The role of managers in assisting work addicts is important because managers should help them prioritize projects both for short and long term. Employees should be given a specific time for breaks and a fixed schedule to start and end the working program. Developing workplace values that promote a healthier and more balanced lifestyle will help people with addiction tendencies to change those dysfunctional behaviors.

References

- Barling, J. & Macewen K., E. (1994). Daily consequences of work interference with family and family interference with work. Work & Stress, 8(3), 244-254.

- Bonebright, C. A., Clay, D. L., & Ankenmann, R. D. (2000). The relationship of workaholism with work–life conflict, life satisfaction, and purpose in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47(4), 469-477. DOI: 10.1037/0022-0167.47.4.469

- Burke, R.J. (1999). ‘It’s not how hard you work but how you work hard: evaluating workaholism components’. International Journal of Stress Management, 6, 225–40.

- Burke, R. J., (2000). Workaholism among Women managers: personal and workplace correlates. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 15(6), 520-534.

- Evans, P., & Bartolomé, F. (1984). The changing pictures of the relationship between career and family. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 9-21.DOI: 10.1002/job.4030050103

- Frone, M., R. Russell, M. Barnes, G., M. (1996). Work-family conflict, gender, and health-related outcomes: a study of employed parents in two community samples. J Occup Health Psychol, Jan, 1(1), 57-69.

- Hammer, L. B., Bauer, T. N., & Grandey, A. A. (2003), .Work-family conflict and work-related withdrawal behaviours. Journal of Business and Psychology, 17(3), 419-436. DOI: 10.1023/A:1022820609967

- Klaft, R. P., & Kleiner, B. H. (1988). Understanding workaholics. Business, 33, 37-40.

- Machlowitz, M. (1980). Workaholics, living with them, working with them, Addison-Wesley Pub. Co., 1980 the University of Michigan.

- McMillan, L. W., O'Driscoll, M. P., & Brady, E. C. (2004). The impact of workaholism on personal relationships. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 32(2), 171– 186. DOI: 10.1080/03069880410001697729

- Mueller, C. W., & Kim, S. W. (2008). The contented female worker: Still a paradox?. In K. A. Hegtvedt & J. Clay-Warner (Eds.), Justice: Advances in group processes volume 25 (pp. 117-150). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?id=rynLSn6zYRkC.

- Naughton, T., J. (1987). A conceptual view of workaholism and implications for career counseling and research. Career development quarterly, 14, 180–187.

- Porter, G. (1996). Organizational impact of workaholism: suggestions for researching the negative outcomes of excessive work. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1, 70–84.

- Reanu Iftime O., (2016), Workaholismul si dinamica vieții de familie, Conferința internațională “Omul – o perpetuă provocare. dimensiuni psihologice, pedagogice și sociale, Sesiune de comunicări științifice studențești, ediția a III-a, Constanța, 9 iunie 2016

- Robinson, B. E., & Post, P. (1995). Work addiction as a function of family of origin and its influence on current family functioning. The Family Journal, 3, 200–206.

- Robinson, B. E., & Chase, N. (2001). High-performing families: Causes, consequences, and clinical solutions, Washington, DC: American Counseling Association.

- Robinson B., E. Jane J. Carroll, & Flowers, C. (2001). Marital Estrangement, Positive Affect, and Locus of Control Among Spouses of Workaholics and Spouses of Nonworkaholics: A National

- Study. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 29(5), 397-410 https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180127624

- Schaef, A. W., & Fassel, D. (1988). The addictive organization. Harper & Row Publishers.

- Schaufeli W. & Bakker A.(2004), Uwes Utrecht Work Engagement Scale, Retrieved from https://www.wilmarschaufeli.nl/publications/Schaufeli/Test%20Manuals/Test_manual_UWES_En glish.pdf

- Spanier, G. B. (1989). Dyadic adjustment scale. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

15 August 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-066-2

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

67

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2235

Subjects

Educational strategies,teacher education, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Enache*, R. G., & Matei, R. S. (2019). Consequences Of Work Dependence On Couple Life. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 67. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1236-1242). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.08.03.152