Abstract

This study aims to reflect on the relationship between families’ socio-economic, cultural and religious circumstances and their children’s success at school. We seek to enquire as to how certain conditions of fragility and inequality of some family groups (due to their origin, religious practice, unstable employment and residential status, and low income) affect families’ participation in schools and their children’s educational success. We also discuss whether socio-cultural diversity is a relevant factor for equity and equal opportunities in our society. To do so, we will present some of the results achieved via three studies carried out by the GRASE (Social and Educational Analysis) research group at the University of Lleida (Spain) continuously from 2015 until the present. The results show that cultural diversity and the fragile socio-economic circumstances of some families, despite appearing as being attended to in the discourses of schools, in their practices analysed, are difficult to materialize; this, together with the frailties of centres the selves (due to cut-backs in the field of social provisions and education by the public authorities, overloads in the ratios of public centres, disquiet among teaching staff, etc.) in some cases involves situations of inequity and risks of educational exclusion.

Keywords: Familiesschoolssocio-economic inequalities

Introduction

It is widely recognized that when attempting to gain greater insight into the framework in which the inclusion of children in schools and in formal learning processes takes place, it is essential to focus the interest of the researcher not only on those factors which, within the school centre enhance learning (such as the characteristics of the educational centre, the management team and the teachers, etc.), the latter, of course, being of great importance, but also on other equally important but perhaps more complex factors, which we may call extra-school factors, mostly related to the family context of the pupil and the social space in which they are all immersed.

Since the last third of the 20th century, Spain and, in particular, the Catalan Autonomous Community, have received a large number of migrants from other continents. Thus, according to data from the Spanish National Institute of Statistics, the percentage registered foreign population grew from 0.63% in 1986 to 16.7% in 2016, with a great variety of origins and cultural and religious traditions.

We will focus our analysis on the impact that the arrival and settlement of the foreign population (mostly young people, accompanied by minors or at procreation age) has had on the education system of the Catalan Autonomous Community (Spain), especially dealing with the qualitative aspects. This autonomous community is one of those that have received a higher proportion of foreigners during the established period, as can be seen in Table

We refer particularly to this population, given that we focus on the existing correlations between educational success and socio-cultural and economic inequalities; and the immigrant population which, on the one hand, has been most hit by the recent economic crisis in Spain and, on the other, combines all “the euphemisms of diversity” at school, as coined by Tarabini (2017, p. 67), (Table

Subsequently, we will provide reflections on the conditions of schooling, policies to meet diversity; educational success and segregated schooling occurring within schools. For the design of social policies that pursue social cohesion, these reflections may be useful.

Problem Statement

In 2013, the Generalitat de Catalunya (Catalan Government), in view of the alarming figures of academic failure, which is at around 30% in this autonomous community, developed a “Plan for the reduction of academic failure in Catalonia 2012-2018”. It defines “educational success” under almost solely quantitative parameters. Thus, the following indicators are identified: suitability rates, repetition rates, graduation rates, and the results of the various assessment tests that the “Consejo Superior de Evaluación del Sistema Educativo” ( Advisory Body to the Ministry of Education of the Generalitat de Catalunya.) wishes to implement (basic skills assessment tests, etc.). From our point of view, the understanding and delimitation of the concept goes far beyond quantitative indicators and we approach the concept from a more holistic definition, including socio-cultural and family variables as well as variables of the school itself.

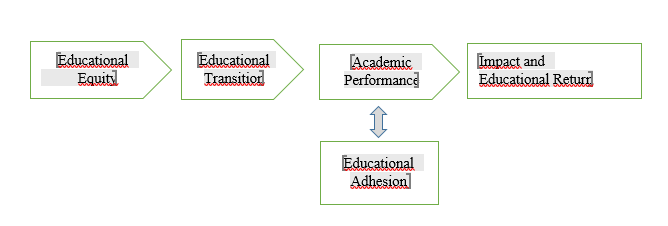

So, we find timely the conceptual approach to educational success proposed by the Bofill Foundation in its Yearbook (Albaigés and Ferrer-Estebán, 2016) which construes education from a broad perspective, not restricted only to the scope of the formal education system, but also to other systems that educate beyond school (family, leisure, culture, etc.). As a result, it analyses the phenomenon of educational success in its various dimensions, based on indicators related to academic performance, of course, but also related to equity (segregated schooling, for example), educational adhesion (continuity at the centre, for example), educational transition (between educational centres-levels, for example) and educational impact (the child’s socio-economic and cultural development, for example).

According to this criterion, the socio-cultural and economic circumstances of families will influence the qualities in which the schooling of the children in their charge takes place and their educational success. This relationship is synthesized by Garcia Alegre (2014) in Figure

If we ask ourselves what the most disadvantaged groups in Catalonia are today, we will conclude that several studies have been conducted on vulnerable groups in Catalonia since the economic crisis of 2007 and all of them agree as to how it has mushroomed, especially among families of foreign origin.

Let us cite, without limitation: the “Report on the Integration of Immigrants in Catalunya” in 2015, in a cross-sectional analysis from 2008 to 2015, points out that the rate of unemployment among the foreign population in Catalonia trebles that of Spaniards. And studies by the European Anti-Poverty Network (AEPN) ( http://www.eapn.es/estadodepobreza/ ) on poverty in Spain have highlighted in recent years the major divergences between the AROPE (At-Risk-Of Poverty and Exclusion) rate for the Spanish population and the foreign population for all years (2008-2016), with differences ranging between 29 and 38 percentage points higher. The study is quite categorical in asserting that nearly two out of every three foreign nationals from outside the EU (60.1%) were in a situation of poverty or social exclusion in 2016 (the last year for which figures are available).

And, to get an idea of their quantitative composition, according to data from IDESCAT (Statistical Institute of Catalonia https://www.idescat.cat ) , in 2017 Catalonia was host to 13.8% of the resident foreign population; but to understand the impact of immigration in this autonomous community we also note that around 20,000 Spanish nationality documents are granted each year to people of foreign origin.

Regarding another issue, studies on inequalities in education centres are not new to social studies. Since the emergence of the so-called Coleman Report, there has been a huge amount of sociological literature dedicated to the analysis of inequalities in educational outcomes and the weight of the social factors associated with these inequalities (Carabaña, 2016). One of the most controversial findings of this report was that strictly school-related factors (curricular organization or teaching model) had very little impact on the inequality of educational outcomes [see the review of Carabaña (2016)].

Based on the empirical observation of an existing relationship between results at school and students’ social origin, numerous investigations have been carried out to ascertain the factors that explain this situation. The majority of such investigations come within the so-called “social reproduction” movements that attribute to the economic, cultural, symbolic, or linguistic capital of families the causal effect to explain why the children of the most disadvantaged classes enjoy less success in academic achievement (Ruiz-Valenzuela, 2017; Gratacós and Ugidos, 2011). In recent years, this perspective has been reinforced by the relation between ability and the socio-economic status of families measured by the OECD (2013). In any case, and unequivocally, it is among “diverse” students or “students of minority cultural origin”, as Gratacós and Ugidos (2011) define them, that the mentioned correlations -educational success-socio-cultural and economic inequalities-, appear to establish a perverse cycle.

From this perspective, the distance between school achievement and social origin would be mediated, when not reinforced, by selective institutional practices (organizational and pedagogical), whether with regard to access (choice of school, distinction between public school and private school, etc.) or to the process (segregated schooling, level of performance, school environment, etc.). A great many studies already show that it is the structure and logic of the educational system that maintain and create new inequalities among its students (Bolivar, 2005) with practices of segregated schooling according to degrees of knowledge that are highly related to social origin (Pamies and Castejón, 2015). Torrents, Merino, García, & Valls (2018) demonstrate that among the factors influencing unequal educational outcomes, the inequality of results can be explained rather by segregated schooling than the organizational model of the centres. Pupils coming from working families are more disadvantaged if schooled at centres where the working class is in the majority, whereas the curricular organization of the centre has a very minor impact on the results. And Tarabini (2017) concludes in her study that, in schools, the internal mechanisms of curricular diversification and the teachers’ own expectations (negative or positive towards the pupil’s possibilities) are two very powerful factors in the dynamics of failure, abandonment or success in the education system by pupils from families with greater socio-cultural diversity.

And finally, among the factors that we have identified as “extra-centre” we would echo some “Local Education Policies”, known as “Planes de Entorno” (environment plans) that were promoted in Catalonia under the LEC (Catalan Education Act) which sought to find synergies between the regional administration and the municipal bodies to combat territorial educational inequalities and seek territorial equity in terms of education and social integration issues in general. The scope of and budget for these policies have shrunk since their inception in 2005 almost to the point of disappearance today. Thus, between the 2005-2006 and 2011-12 academic years, the economic endowments of these Plans were co-funded by the Catalan Government and the Spanish Ministry of Employment and Immigration, within the framework of the support fund for the reception and integration of immigrants. The funding for the 2014-15 and 2015-16 academic years came exclusively from the budget of the Generalitat de Catalunya, and since 2016, those municipalities interested were invited to fund their continuity practically entirely, which, in the opinion of the Pi i Sunyer Foundation (2016) induces many territorial inequities and disparities.

Research Questions

This text reflects the results referring to three of the goals of our research:

-To find out how the policy to meet diversity in public and private centres of education has been developed and establish the plurality of its practical development.

-To analyse the discourses and intercultural practices in education and how they affect the equality of opportunities and the equity of pupils in schools.

-To detect the actions carried out by the various public authorities to promote equal opportunities and equity in schools.

Purpose of the Study

We aim to provide some insights into what is currently being done by the education system to accommodate the increasing social and cultural diversity and what are the difficulties and challenges for tackling equity of access and permanence therein.

Research Methods

Some of the results of three investigations carried out by the GRASE research group at the University of Lleida from 2015 until today are shown:

-Research on “Cultural and religious diversity in primary schools in Catalonia”. Research conducted in the period 2015-2016. Quantitative and qualitative techniques were combined in its performance. Specifically, a first, quantitative phase was developed in which 380 surveys were carried out at public schools. Then, the qualitative phase was implemented, with 21 in-depth interviews with persons in charge of schools, whose experiences were considered especially unique and innovative.

-Research on “Cultural and religious diversity in secondary schools in Catalonia” . Research conducted in the period 2016-17. A mixed methodology was also used for its performance. In a first phase, a survey of 165 secondary schools was carried out and in a second phase, 26 in-depth interviews were held on persons in charge of schools whose experiences were identified as being particularly interesting.

-Research on cultural diversity and equal opportunities in schools in Catalonia. Research conducted from 2016 to the present. In the framework of this research, in 2017 surveys were conducted on 545 representatives of school management teams and seven in-depth interviews were held with representatives of the Education Authorities of the Autonomous Community of Catalonia. Also, a large amount of documentation was collected on the different Planes de Acogida (reception plans) at local administration level in Catalonia’s 42 capitals of the comarcas (“counties”).

Findings

Having listened to the entire education community: school head teachers, teachers, members of parents’ associations, representatives of regional and local authorities, it can be stated that:

We thus note that the factors attributable to the families, their socio-personal or contextual situation are the ones that are most argued by those in charge of the centre. Second, there would be factors attributable to the school, in particular, or the education system (including: financial constraints, high ratios and limited staffing, among others). Attributable to teachers, the following are mentioned: their attitude (7.7%), unsuitable work dynamics (7.3%), their training (5.9%), coordination with other professionals (1.7%), and the teaching methodology they use (5.9%). And thirdly, factors attributable to the pupils. Somehow, the prevailing view is that that the cause of unequal opportunities is rather individual than collective; more private than public; with little self-criticism of teaching methodologies and attitudes.

As can be seen, this reduction took place in all items, although here we highlight that of “employee remuneration” (-11.5%). This indicates that, at a time of greatest deprivation and stress for many families, the human resources that were allocated to the education system were cut back and also specific projects or programmes involving specific attention to diversity, as shown in the attached Table (Table

Conclusion

References

- Albaigés, B., & Ferrer-Estebán, G. (2016). L’estat de l’educació a Catalunya. Anuari 2016. Indicadors sobre l’èxit educatiu a Catalunya. Barcelona: Fundació Bofill.

- Bolivar, A. (2005). ¿Dónde situar los esfuerzos de mejora? Política educativa, escuela y aula. Educação e Sociedade, 26(92), 859-888.

- Carabaña, J. (2016). El informe Coleman, 50 años después. Revista de la Asociación de Sociología de la Educación, 9 (1), 9-21.

- Confederación Sindical de Comisiones Obreras (2016). Cartografía de los recortes. El gasto público en España entre 2009 y 2014. Madrid: CCOO.

- García Alegre, M. P. (2014). Uso de Dispositivos móviles y Herramientas tecnológicas en los centros Educativos. Universidad Jaume I, Alicante

- Generalitat de Catalunya (2013). Pla per a la reducció del fracàs escolar a Catalunya 2012-2018. Barcelona: Departament d’Ensenyament.

- Generalitat de Catalunya (2016). Informe sobre la integració de les persones immigrades a Catalunya 2015. Barcelona: Secretaria d’Igualtat, Migracions i Ciutadania.

- Gratacós, P., & Ugidos, P. (2011). Diversitat cultural i exclusió escolar. Dinàmiques educatives, relacions interpersonals i actituds del professorat. Barcelona: Fundació Bofill.

- OECD (2013). PISA 2012 Results: What Makes Schools Successful? Resources, Policies and Practices, IV. París: OECD Publishing. DOI:

- Pamies, J., & Castejón, A. (2015). Distribuyendo oportunidades: El impacto de los agrupamientos escolares en la experiencia de los estudiantes. Revista de la Asociación de Sociología de la Educación, 8 (3), 335-348.

- Pi i Sunyer Foundation (2016). Fundació Carles Pi i Sunyer s´studis autonòmics i locals. Retrieved from: https://pisunyer.org/

- Ruiz-Valenzuela, J. (2017) L’impacte de la temporalitat i la pèrdua de treball parental en el rendiment educatiu dels fills. Barcelona, Fundació Caixa de Pensions. Retrieved from: https://observatoriosociallacaixa.org/ca/article/-/asset_publisher/ATa

- Tarabini, A. (2017). L’escola no és per tu: el rol dels centres educatius en l’abandonament escolar. Informes Breus, 65. Barcelona : Fundació Bofill.

- Torres, T., Farré, M., & Sala, M. (2018). Financement de la diversité culturelle au sein de l’école catalane. Actas del Seminario internacional : educación y diversidad cultural, celebrado en la Universidad de Lleida en marzo de 2018.

- Torrents, D., Merino, R., García, M., & Valls, O. (2018). El peso del origen social y del centro escolar en la desigualdad de resultados al final de la escuela obligatoria. Papers, 103(1), 29-50

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

09 April 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-059-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

60

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1062

Subjects

Multicultural education, education, personal health, public health, social discrimination,social inequality

Cite this article as:

Mata, A. (2019). How Families’ Socio-Economic Inequalities Affect Schools. In E. Soriano, C. Sleeter, M. Antonia Casanova, R. M. Zapata, & V. C. Cala (Eds.), The Value of Education and Health for a Global, Transcultural World, vol 60. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 651-659). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.04.02.81