Abstract

Educators may incur tortious liability for harm caused to their charges. A tort is an actionable action against one person by another. Liability may result from acts involving negligent conduct. Tortious and negligent conduct engulfing educators commonly involve issues over the conduct of pedagogic activities, field trip and academic evaluation among many others. The study applied library research by collating records from various educational, general orders, ministry circulars, pedagogical practices, customs and judicial decisions that educators should be knowledgeable. The empirical study adopted a sequential mixed method of quantitative and qualitative methodology by administering a semi-structured questionnaire to a convenient random sample of 200 respondents of educators from the public and private educational institutions in Kuala Lumpur via online application. The survey was complemented by an open-ended interviews with 5 experienced educators to solicit and verify the data gathered from the survey thereto. Descriptive statistics and inferential statistical analysis were applied, while independent-samples t-tests were used to analyze the data. Results showed that more than 80% of the educators lacked the knowledge on how to handle tortious issues.The results of the t-tests point to a no significant difference between public educators and private educators from the public and private educational institutions. The findings suggest the importance to raise the level of awareness and understanding of the educators by introducing a basic course in the tort liability in their vocational training as a preventive measure so as to elude tortious act and further humanize the pedagogical competency.

Keywords: Educatorstortious liabilitynegligentpedagogy

Introduction

Educators would be liable for any tortious act which caused their charges to suffer injuries from negligent conduct. Alsagoff (2015) commented that a tort is a civil wrong committed by an individual or a number of individuals. The aggrieved injured party may claim monetary compensation for the injury caused either by intentional or unintentional torts; or may seek an injunction order from the court to prevent future harm. Tort liability also gives options for the injured party to file charges for injury to their reputations. The sources of tort law in Malaysia are derived from the English common law, the common law principles and the decisions of the local courts. In the educational environment, a tort may involve a class action suit against an educator and/ or the management depending on the circumstances surrounding the injury. Before a court grant redress, it has to determine whether there is actual fault and the claims of liability are supported by the injuries that occurred at the time (Essex, 2012). By definition an educator refers to a person who teaches and administers educational programs at the lower and higher educational institutions. Their professional conducts are governed by several legislations relating to education, i.e., the Education Act 1996 (Act 550), the Private Higher Educational Institutions Act 1996 (Act 555), the Malaysian Qualifications Agency Act 2007 (Act 679), the Universities and University Colleges Act 1971 (Act 30) and Perintah-Perintah Am Dan Arahan Pentadbiran 1980. In the course of discharging their duties, an educator is expected to observe due diligence and may be liable for tortious act for the harm caused to their charges thereto. The educator as an executive is duty bound to observe the standard of care in the course of their work. For the purpose of this study, the educator is defined broadly to include educators from the public and private educational institutions. By appointment an educator may be designated as: deans, assistant deans, principals, vice-principals, district educators, president, chief academic officers, presidents, vice-presidents, vice-chancellors, rectors, deputy rectors, directors, department heads, chairpersons, registrars and directors of administration (Section

Literature Review

There are many areas of the laws that affect educators globally. Tulasiewicz and Strowbridge (1994) commented that there have been many legal issues in education that have originated from the problems of law and education as reported from the international precedents. In the instance, the courts of most countries have decided on issues of the structure of educational systems. Ruff (2005) remarked that there has been a dramatic increase in education legislation and litigation by parents and students in the last 20 years. Education law has become a dynamic subject. It cuts across traditional teaching boundaries and is influenced by work in other disciplines. It draws its roots in administrative law, torts, child law, discrimination law and human rights legislations of which are of crucial importance. Nevertheless, it is noted that these scholars did not cover many aspects of legal issues in education under the law of contract, torts, constitutional or even under the criminal law. In discussing the widespread impact of the law of education to the educational environment, Kaplin (2013) opined that the laws relating to education have regulated the life of the academics, administrative staff and students on the campus. Its impacts on the daily affairs of post-secondary institutions have grown continuously over the decades. This covers not only whether one is responding to campus disputes, planning to avoid future disputes, or charting the institution’s policies and priorities. The law remains an indispensable consideration. Legal issues arising on campuses across America also continue to be aired not only within the groves of academia but also in external forums. For example, students, faculty members, staff members and their institutions are frequent litigants in the courts. As this trend continues, more and more questions of educational policy and practice become converted into legal questions as well. Litigation has extended into every corner of campus or school activity. However, this situation has yet to reach such unprecedented scale in Malaysia as our society is not litigious people. Fischer, Schimmel & Stellman (2012) further commented that today’s educational institutions operate in a complex legal environment where a gamut of legal disputes affects the daily lives of educators, students and parentages. Too many teachers view the law with anxiety and fear. They are excessively fearful of being sued as many teachers are poorly informed about the law that affects them. Most teachers do not know that this law exists, or almost do not know about this subject or have had little training in applying education law during their professional careers. This state of affairs was illustrated by Birch & Richter, (1990) who commented that certain school activities traditionally carried out by teachers were not in fact contractual but voluntary. The matter has not been clearly pronounced that there is no agreed definition of the teacher’s day and duties. This includes, inter alia, the supervision of students during breaks, refusal to accept ‘duties’ of student supervision immediately before and after school to keep them safe within the school premises, attendance to the parents’ or staff meetings out of term time and extra-curricular activities. Thus, given the lack of awareness and understanding on the legal status of these activities have caused incidences of alleged educational negligence being committed by educators.

Educators are given varied responsibilities under their contract of employment. Among the major tasks they have to include: performing, teaching and learning activities, inter alia, choosing the methods and content for teaching, evaluating student performance and conducting non-teaching duties in and out of campus. They are exposed constantly to the many potential risks while conducting their duties. These duties may extend beyond the walls of the school and the hours of operation and varies with the pedagogical assignments and circumstances. Thus, when injuries resulted, the student’s family or guardian would sue for damages. However, where an educator observes due diligence to prevent injuries, but somehow accident still occurs, there is no liability. Therefore, it is advisable for educators being judicious in discharging their duties. Under the common law, an aggrieved party has the option to seek legal remedy either in contract or tort for his injuries suffered. The area of overlap between tort and contract has increased significantly over the years. Litigants have been active in searching for the possibility of an action against a defendant in both contract and tort. Although a plaintiff cannot recover twice for the same injury, he may by suing in contract to avoid an obstacle to an action in tort or vice versa (Midland Bank Trust Co Ltd v Hett, Stubbs and Kemp [1979] Ch 384, [1978] 3 All ER 571, Cf Bell v. Peter Browne & Co [1990] 2 QB 495, [1990] 3 All 353 ER 124). In Henderson v. Merrett Syndicates Ltd [1995] 2 AC 145, [1994] 3 WLR 761, the House of Lords broadened the law in the context of concurrent actions in contract and tort by holding that the plaintiff had an option as to which action to pursue. This was seen in Junior Books v. Veitchi Co Ltd [1983] 1AC 520, [1982] 3 All ER 201, a plaintiff whose remedy lies in contract against one defendant has been successful in a tort action against a different defendant. The House of Lords held that on such facts the plaintiffs could have an action in tort against the defendants even though there was no danger of physical injury or property damage to the plaintiffs. The possibility of an alternative tort action on such facts is clearly of great theoretical and practical significance and has led to much discussion (Furmston, 1986).

Tortious liability arises when an educator has a legal duty of care towards the students, but failed to maintain this standard. The usual liability falls under intentional or unintentional torts. Intentional torts are those involving “assault, battery, libel, slander, defamation, false arrest, malicious prosecution, and invasion of privacy require proof of intent or willfulness”. Unintentional tort such as negligence does not need proof of intention. Liability burdens would stand where it can be shown that the educators or officials had acted inappropriately in causing harm to students (Imber, Geel, Blockkhuis, & Feldman, 2014). The educators performed varied academic activities. Among the tasks they have to perform besides teaching, include other matters related to the pedagogs, i.e., designing and developing the program curriculum, methods and content for instruction, selection of academic staff for teaching assignment, selection of qualified students in various programs, supervision and evaluation of the performance of academic staff and students. Some of the responsibilities associated with these roles are influenced by parents, community and educational authority’s wishes (Abdul Hamid & Nik Mohammad, 2016).

Educational institutions have to implement the ministry’s curriculum in their teaching and learning activities which are stipulated via its education policies, regulations and laws. The state education department and local school board may provide further guidelines and instructions as to how they may select activities and materials within these broad guidelines. If an educator breached the professional standards, disciplinary action, such as cautioning against the use of the prohibited material or methods might ensue. However, academic freedom does not restrict them in interpreting the curriculum, nor are they encouraged to ‘follow the text’ without applying its relationships to the real world. Educators are encouraged to teach the subjects assigned to them creatively and innovatively. The program of studies offered to students must provide diverse option of subjects that students can choose for a particular discipline according to the course structure. Any deviation from it may result in potential tortious liability (Abdul Hamid & Nik Mohammad, 2016). The education authorities can be vicariously liable for the negligent act of their personnel. Under the concept of respondeat superior, the employer is accountable for official acts of its employees or agents. Thus, the board of management can be vicariously liable if the principal is found guilty for the tortious conducts of the educators, even if it is not guilty. However, under the vicarious liability principle, the educator must act within the scope of the assigned duties. This concept commonly involves a negligence suit where in a class action the educator and the education authority is sued for alleged negligence by an educator under its employment. In matters of tortious liability for negligent conduct of the staff or public or suppliers or contractors, the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Higher Education shall be solely responsible to handle the case and shall refer any legal issues arising to the Attorney-General for legal advice on the necessary course of action to be taken. The Ministry’s legal counsel shall be responsible to follow-up on the matter to be resolved. On the same premise, the contractual liability of the private educational institutions is governed by the contractual agreement entered into between the parties. This may include the academic staff or suppliers or contractors or public. The Government Proceedings Ordinance of 1956 (F.M. 58 of 1956) shall be applicable solely to the public educational institutions. Section

Educators are responsible for their own tortious acts at their workplace. There were instances of reported cases where these officials have been sued for negligent conduct in educational supervision, involving accidents in school or during field trips. For instance, in the United States and United Kingdom when educators were sued by their students or parents for negligent teaching or educational malpractice the usual course of action against is to sue for breach of contract. Where such action failed the next recourse is to sue on grounds of tortious liability and in the final recourse the litigants may sue for breach of constitutional rights. Nonetheless, such situation has yet to occur in Malaysia. However, given the House of Lords decisions in E (a minor) v. Dorset County Council; Christmas v. Hampshire County Council; Keating v. London Borough of Bromley [1995] 3 All ER 353 and Phelps v. London of Hilington [1998] E.L.R. 389 as case precedents for negligent academic evaluation may open doors to future litigations in educational negligence in teaching to spill into the Malaysian courts. It must be highlighted that the United States courts have been reluctant so far to find teachers liable in common law for negligent teaching or educational malpractice on grounds of public policy, except in the states of Montana and New York, where the courts were inclined to accept such cause of actions as held in Snow v. State, 98 AD 2d 442; 469 NYS 2d 959 (1983); 64 NY 2d 745; 47855 NE 2d 454; 485 NYS 2d 987 (1984). Since the 1970s, there were a few case precedents and the courts rejected the idea of educational negligence as a cause of action for policy reasons. For instance, Peter W. v. San Francisco Unified School District, 60 CA App 3d Cal Rptr 854.0 (1976) where an 18 year old high school graduate sued his school district for negligence in failing to provide an adequate education because he could not read at the fifth grade level. He claimed that the school personnel had failed to exercise the degree of professional skill required of ordinary prudent teachers. This negligence was evident in the school district’s failure to capture his reading disability, use of inadequate or incompetent teachers and allowing him to pass to a higher class each year despite his lack of the required abilities to progress. The court affirmed the trial judge’s decision to dismiss the case because it failed to state a cause of action. The court stated that it was impossible to identify a workable standard of care applicable to teachers and the difficulty in isolating the cause of the plaintiff’s failure to learn as the science of pedagogy itself is laden with different and conflicting theories of how or what a child should be taught. The judge concluded by expressing serious concern that allowing such action to succeed would result in floodgates of similar suits that would be counterproductive to public policy. Likewise, in Donohue v. Copiague Union Free School District, 64 AD 2d 29; 407 NYS 2d 874 (1987); 47 NY 2d 440; 391 NE 2d 1352; 418 NYS 2d 375 (1979) similar facts were alleged. Although the plaintiff graduated from high school, he lacked “even the rudimentary ability to comprehend a level sufficient to enable him to complete applications for employment.” The New York Court of Appeals observed that it may be possible to state a legally sufficient claim alleging educational negligence within the established principles of negligence and stated that the creation of a standard with which to judge a teacher’s performance would not necessarily be an insurmountable obstacle. However, the court was unwilling to let the action succeed for explicit public policy reasons. The court stated that a cause of action for damages against a school district for educational malpractice is not cognizable in the courts as a matter of public policy, since the control and management of educational affairs are vested in the Board of Regents and the Commissioner of Education. Thus, the court felt that it should not interfere with such affairs as students and their parents could still take advantage of the administrative process to seek the assistance of the Commissioner of Education in ensuring that such students receive a proper education. Despite the almost uniform rejection of educational negligence claims in the United States on public policy grounds, however, such suits may be successful in the future as some states had ruled against such policy considerations. This was seen in B.M. v. State, 48 649 P 2d 425 1982 where the Supreme Court of Montana held that the school authorities owe a child a duty of reasonable care in testing the child and placing him or her in an appropriate special education program. The court found this duty to rise from the Montana Constitution and other statutes, and held there was a common law duty of care along the same lines as required by the legislation under consideration. The judgment is significant because the court did not believe it necessary to deny the establishment of a duty of care for policy reasons cited in the foregoing cases. In the United Kingdom, the House of Lords in E (a minor) v. Dorset County Council; Christmas v. Hampshire County Council; Keating v. London Borough of Bromley [1998] E.L.R. 389 indicated that the common law of the United Kingdom is developing in a different direction from the common law of the United States. In each of the three actions, the defendant was an education authority. Each of the plaintiffs complained of acts done or not done by the education authority during his minority. Damages were claimed for breach of statutory duty and common law negligence or (in one case) common law negligence alone. This was the first case in which the House of Lords had to consider the liability of schools and teachers for the intellectual development of their students. The court found that where children appear to be experiencing difficulties with their school works, teachers have a duty of care when assessing and advising on their educational needs. This case did not deal with other forms of negligent or inadequate teaching, such as frequent absence from classes or malingering during classes, teaching the wrong subject content or failure to cover compulsory components of curriculum or syllabi, giving poor explanations of concepts, ideas and facts or careless evaluation of students, work which resulted in students’ obtaining low marks or causing the students to suffer from severe emotional distress and phobia to attend school. The House of Lords decision was applied in Phelps v. London of Hilington [1998] E.L.R. 389 where the plaintiff claimed that the defendants as the local education authority (LEA) with responsibility for her education had been negligent at common law in failing to identify her as having a special learning difficulty or dyslexia and failing to take appropriate remedial steps. She further alleged that had such steps being taken, she would achieve a substantially higher level of literacy, then and that her prospects of better employment would have correspondingly increased. It was held by the House of Lords that the local education authority was in breach of its duty of care because in 1985 an educational psychologist employed by the LEA (Local Education Authority) failed to diagnose that the plaintiff was dyslexic. The LEA had also failed to reconsider her initial diagnosis of emotional difficulties despite continued poor performance. The plaintiff was diagnosed as dyslexic in 1990 when she was 16 years old. The judge further held that damages of £44,056.50 were recoverable for her “loss of confidence, low self-esteem, embarrassment, and social unease.” The decision in Phelps was taken purely from a common law consideration arising from a cause of action in the context of negligence in tort and no policy consideration was ever considered, unlike the position taken by the United States courts where public interests consideration override legal consideration in deciding whether to award compensation to students who suffered educational negligence claims.

Under the Malaysian context, co-curricular activities are declared to be a fundamental part of a student’s educational process. The educator’s involvements in such activities are sanctioned by the Ministry of Education as part of the National Curriculum (Section

Unlike the situations in the United States and United Kingdom, there are no reported cases involving educators or institutions being sued by students or parents for negligent teaching but more for the tort of negligence in educational supervision. Educators are expected to provide reasonable supervision of students depending on the pedagogical activity. The intensity of supervision increases with the age of the students and the potential of greater risk for injury to occur while involving on and off campus activities. Thus, the level of standards of care differs depending on the kind of activity in a given situation. The courts would take into account factors such as the type of educational program involved, age and total number of students involved in the activity and the diligence of supervision. For instance, in the case of Headmistress Methodist Girls’ School & Ors v Headmaster Anglo Chinese Primary School & Anor [1984] 1 MLJ 293 where a pupil aged 9 years had an accident when she was hit by a school bus while walking in the compound of the school on her way home. She sustained serious injuries and sued the appellants, the bus owners and the driver, the Headmaster of the school and the Government as the third party, for damages. They claimed contribution in the event of liability against them on the ground that the school authorities were also partly liable for allowing the bus to enter the school compound. The court held that owners and occupiers of the premises the school authorities were under a duty to keep the school premises safe. While in the Government of Malaysia & Ors. v. Jumat Bin Mahmud & Anor [1977] 2 MLJ 103 the plaintiff was injured in his right eye when another pupil, Azmi bin Manan took advantage of his teacher’s slack of momentary attention in class by pricking the plaintiff’s thigh with a pin. This shocked the latter and when he turned round, his right eye poked into the sharp end of the pencil which Azmi was holding. The eye was removed subsequently. Azmi said it was an accident. Azmi was a playful boy and had on previous occasions poked the plaintiff and other boys with a pin or pencil but never in their eyes, and that was done without the knowledge of the form teacher, Mrs. Kenny. The trial judge agreed that he did not deliberately stab the plaintiff’s eye with a pencil. At the time of the accident Mrs. Kenny had given written work to the class of 40 pupils and was working at her desk. It was argued that there was a lack of supervision by Mrs. Kenny, thus resulting in the accident which caused the injury to the plaintiff. The High Court held that there had not been sufficient or reasonable supervision by the form mistress at that material time and that the injury was caused by her negligence. The appellants appealed to the Federal Court. The court held that there was no evidence that the class lacked supervision from the form teacher as Mrs. Kenny knew of Azmi’s propensity to wander about and she would immediately ask him to return to his desk which he did. The trial judge had failed to provide evidence that the injury sustained by the plaintiff was of a kind reasonably foreseeable as a result of Mrs. Kenny’s wrongful act, assuming she was wrongful. In another negligence case involving field trip was seen in Chen Soon Lee v. Chong Voon Pin & Ors [1966] 2 MLJ 264 the defendants, a principal and teachers had gone, unofficially, with fifty-three students for a picnic by the sea. The deceased and her friends were playing a ball game in waist deep water when some of them got into a deep depression and struggled themselves in difficulty. The teachers and some boys came to their assistance, but found that the deceased was missing. A search was carried out and the deceased was found in very shallow water. They tried artificial respiration, but failed to revive her and she died. The parents of the deceased student sued the school for negligent supervision. The court held that educators, i.e. principals and teachers owed no duty to the deceased or her father to provide supervision. Even assuming that the principal and the teachers owed such a duty, they had done all they possibly could to ensure the safety of the students and the action must therefore be dismissed.

By definition educational malpractice is any unprofessional conduct or performance lacking of competency in discharging official duties. It represents a recurrent issue, but has surfaced as a new kind of injury to students due to better awareness of societal over their legal rights. These injuries involve emotional, psychological, or intellectual harms which arise from ill prepared teaching, wrongful evaluation, or class placement. The courts had held that educators have the duty to teach, to manage and to ensure the safety of students, any contravention of such duties which cause injuries upon the charges may offer strong reasons for a legal action. There has been increasing tendencies of students suing for academic injuries involving educators and institutions over alleged failure to satisfy the minimum standards of course offerings or even pedagogic competency. Several legal suits were reported in the past, but none of it has been won by parents or students. Nonetheless, with the introduction of school-based course evaluation, curriculum standards and professionalism would enhance the chances of success in an educational malpractice suit.

Educational negligence is often classified as a claim in tort. The most challenging task to argue in favor of allowing educational negligence claims is to bring such claims within established common law principles. There are three common law principles that can be proposed for possible cause of action, i.e., breach of contractual agreement, negligent misrepresentation and negligence, and the potentials and difficulties that each represents for imposing liability for negligent supervision and/or incompetent teaching. An initial problem considering contract as a means of imposing liability for incompetent teaching is that the relationship between an educator and student is not governed by specific or express contractual terms, especially in the context of the provision of education in public schools. This is particularly so in the case of free public education, although it would appear that educational negligence claim based on a contract theory is more practical in the private school context.

This was seen in Commonwealth of Australia v. Introvigne (1980) 32 ALR 251, (1982) 41 A.L.R. 577 the plaintiff was 15 years old when he attended the Woden Valley High School in the Australian Capital Territory. He was grievously injured when the top of a flagpole fell on him. It fell because a group of boys, including Introvigne, was swinging on the halyard which ran through the pulley on the flagpole and swung free below. There were no teachers on duty at that moment to stop them because the teachers were at a meeting with the acting principal of the school. Usually, there would be 5 to 20 teachers supervising the students. During that time, schools in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) were administered by the state which appoint and control the teachers. Introvigne sued for damages in the Supreme Court of the Australian Capital Territory. The first defendant was the Commonwealth of Australia. The Commonwealth had established the school and the Commonwealth maintained it. The learned trial judge rejected the claim against the defendants. The plaintiff's action was dismissed. But the Full Court of the Federal Court allowed an appeal by the plaintiff against the ruling in support of the Commonwealth. It remitted the action to the Supreme Court to reassess the plaintiff's damages.

With respect to public schools, it can be argued that there is an implied contract between educators and students. One of which is that student will not be supervised or taught negligently. Whether there is consideration to support the contract is a difficult question. Thus, consideration may be found in the decision of the student to attend school in reliance to the implied promise of non-negligent supervision and/or teaching. However, the “bargained-for” element of consideration would seem to be lacking where the student attends school under a system of compulsory education, but this does not prevent a tortious action from being pursued to seek redress. In Collins v. Godefroy (1831) QB & Ad 950, 109 ER 1040 it is well established that a person who is already under a duty imposed by law cannot be taken as consideration to support a contract. Therefore, if educators have a public duty to provide non-negligent education, this will not of itself constitute consideration for an implied contract to fulfil that duty. However, carrying out a legal duty in a manner that is above the call of duty may be consideration. Under the implied contractual obligations, educators are expected to act according to the faithful and honest service, to obey, to lawful orders and to work competently and diligently. On the other hand, the employer has to provide a safe workplace, to indemnify employees against loss and to pay the agreed wages. These principles were seen in Wiseman v. Salford City Council [1981] IRLR 202 a drama teacher with responsibilities for 16-19 year-old had two convictions for gross indecency in the public lavatory. The second conviction was reported in the newspapers and came to the attention of the principal of the college where he was employed. The offense was serious and in a public place. Moreover, there was a similar prior incident which should have warned the applicant. The applicant’s work involved close contact with young people and he did not think that a responsible authority would be justified in taking such a risk once it was known that the applicant had been convicted of gross indecency on the one occasion. It was decided that it was justifiable to dismiss him, in part because it was accepted that he could constitute a risk to his students, especially since drama teaching often involved close physical contact with them. However, perhaps equally important was the fact that it was thought that the publicity surrounding the teacher’s prosecution reflected badly on the reputation of the college. In another case in Sim v. Rotherham MBC [1986] 3 All ER, [1986] IRLR 391 a leading case of relevance till today, concerned a group of teachers who refused to provide cover for absent colleagues pursuance to a pay dispute. The National Union of Teachers (NUT) instructed its members not to do so. Accordingly, each of the plaintiffs, secondary school teachers, refused a request to provide cover for a 35-minute school period. The Local Education Authorities regarded compliance with requests to provide cover as a matter of contractual obligation. They deducted from each of the teacher’s monthly salary a sum to represent the failure of the teacher to take the class assigned for the period, calculated on a time apportionment basis. The teachers’ union argued that although teachers were sometimes prepared to provide cover it was a matter of ‘goodwill’; it was not a formal term of contract and could not therefore be a basis of a lawful order. The teachers sued to recover the sums deducted. The High Court held that compliance by the plaintiff secondary school teachers with requests from headmaster to provide cover for absent colleagues during normal school hours was an implied contractual obligation and not a matter of goodwill. The plaintiffs’ refusal to provide cover for a 35-minute period as part of the pay dispute between their union and the employers, therefore, was a breach of contract. Similarly, in Weddell v. Newscastle upon Tyne Corporation [1973] 3 All ER, a teacher with fourteen years’ experience had been frequently reported late to school and was unable to control his class. On one visit to his class, pupils were found laughing, barging about and listening to the Derby race on a radio. It was decided that his level of capability to control his class and teach were below the acceptable one. Also in Haddow v. ILEA [1979] 3 All ER a number of complaints had surfaced about teaching and discipline standards at the William Tyndale School in north London. There was evidence of inefficient and unstructured teaching as well as an uncaring attitude towards many of the students at the school. The Auld Enquiry, established the detailed facts after a long investigation. Several of the teachers were held to be below the level of competence required by contract.

It is possible to formulate a factual situation where an action for educational negligence based upon negligent misrepresentation and negligence may succeed. As this is an action based on tort it needs to be considered whether a duty of care is owed to the plaintiff. In this respect, it is important to note a major distinction between negligent misrepresentation forming the basis of educational negligence claims and educational negligence claims based otherwise than on negligent misrepresentation. In the former case, negligent misrepresentation addresses the issue of whether there is a duty of care on the part of the educators and/or the school authorities to provide non-negligent advice and information. In the latter case, educational negligence raises the issue of whether there is a duty of care on the part of educators and school authorities to provide non-negligent educational supervision and instruction. The case of Mutual Life and Citizens’ Assurance Co. Ltd. & Anor v. Clive Raleigh Evatt (1986) 122 CLR 556 (High Court); (1970) 122 CLR 628 (Privy Council) supported the concerns when the majority of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council held that a person comes under a duty of care with respect to the provision of advice and information if such person carries on a business, profession or occupation and provides advice, or information of a kind which requires skill or competence, or if a person professes to possess skill and competence in the subject matter of the advice or information. This ruling reflects the stringent requirements expected of educators based on their professional qualifications, experience and competency. These conditions certainly place them as experts who offer information or advice of a professional or serious business nature. In the educational context, students and parents would rely and trust the information or advice rendered by these professionals.

Problem Statement

Commercialization of education has pressured the authority to evaluate educational institutions against the international standards. Common legal suits on educational malpractice by students or parents involve breach of duty of care involving, inter alia, pedagogic matters such as teaching and learning, academic evaluation and in and off campus supervision of academic activities. Typically an aggrieved party would seek redress for contractual breach, but when it fails an action for damages for tortious liability would be sought. The rise in litigation over educational malpractice has tarnished the image of educators and the authority. This matter is exacerbated by the lack of educators’ knowledge of tort law. But there is an absence of training in tort laws and/or laws relating to education being offered to educators during the pre-service, in-service or post-service period of their career, thus creating a knowledge gap in the tortious act and liability among educators.

Research Questions

The study was designed to answer the questions on educators’ tortious liability knowledge.

What are the knowledge levels of tort liability among the educators in the study?

Is there a statistically significant difference in the knowledge levels of tort liability between public and private educators?

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was to examine the knowledge levels of tort liability among the local educators which could affect their well- being and pedagogical competency in discharging duties at the workplace. The study also set to determine if statistically significant differences existed between the public and private educators. The comparison was made with the purpose of setting up specific tort liability training for educators as part of the professional development training.

Research Methods

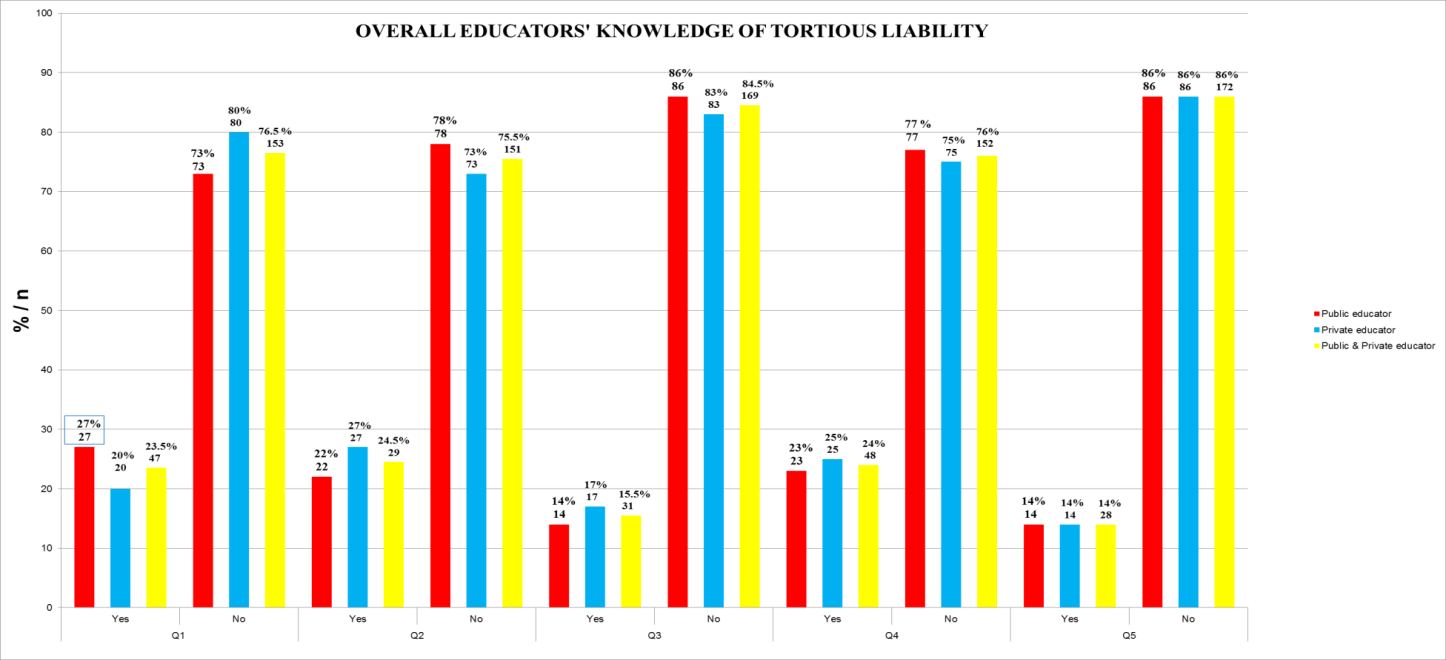

The study was a cross-sectional designed to identify the levels of educators’ knowledge of tort liability and to compare also these levels between the public and private educational educators. The sample consisted of 100 public and 100 private educators from the local educational institutions in Kuala Lumpur, making a total of 200 sample population. The questionnaires were administered online using the Google Form. The researchers used a number of follow-up measures, i.e. email reminders and phone calls to ensure a high response rate. The response rate was 100%. Data were collected using a self-developed questionnaire that contained 5 tort liability knowledge items which asked the respondents to rate, on a 5- point Likert scale (High, Quite High, No Comment, Maybe and None) the degree of their knowledge on tort liability. After being generated, the items were subjected to validation by a psychometric expert and later pilot tested on a representative sample of the target respondents. The reliability of the data generated from the items was found to be high, i.e. a=0.92 showing a good indicator of reliability of the study. To address the research question responses to the 5 Likert items on knowledge of tort liability was collapsed and the mean percentage for each response category, i.e. High, Quite High, No Comment, Maybe and None, was computed. To address the research question 1 and 2, the responses to the 5 items were graded and given a score, i.e. 3 for High/ Quite High, 0 for No Comment, 1 for Maybe and 0 for None. The scores were then summated, yielding a group score each for respondents. Two independent- samples t-tests were performed on the group scores to see if statistically significant differences existed between the groups with respect to the levels of tort liability knowledge. The level of statistical significance adopted for the analysis was p ≤ 0.05, which formed the basis of whether a significant difference existed between the groups or not. The first question asked “What is the level of tort liability knowledge among the educators in the study? While the second research asked “Is there a statistically significant difference in the levels of tort liability knowledge between public and private educators?” A percentage analysis of the five Likert items of the first research question is presented in Chart 1 and Table

The results point to a no-significance between the group score of public and private educators. Although private educators yielded a higher mean score (M= 5.93, SD= 4.17) than public educators (M=5.86, SD=4.17) this difference was not statistically significant. It can be concluded that both groups are about equal in terms of tort liability knowledge (i.e. t (198), df =-0.119, p =0.906).

The independent sample t-test analysis was conducted to examine the differences between public and private in terms of their knowledge. The study involved 200 respondents of educators from the public (100 respondents) and private educational institutions (100 respondents). The result of the study showed that there is no statistically significant difference between those two groups at t (198) = -0.119, p = 0.906. Even though the private educators (M = 5.93, SD = 4.18) was more knowledgeable than public educators (M = 5.86, SD = 4.17) but that difference is still not a statistically significant. This shows that the two groups are equally not knowledgeable about tort liability.

Findings

Several important findings were derived from the study. First, the public and private educators generally have low levels of tort liability knowledge or none at all. Almost half of the respondents reported having no knowledge about the subject matter. The result implied that there is a strong likelihood of finding more Malaysian educators who would not know about tortious act and liability per se. Second, the public and private educators do not appear to differ in their lack of knowledge of tortious liability. A conclusive observation is that a vast majority of the educators has not taken any course on law subject or have no knowledge of acts that could entrap them to be tortious in nature. This finding revealed that even though educators have been trained and knowledgeable in pedagogy, educational psychology or educational administration, they did not know what constitutes conduct unbecoming of an educator when dealing with their charges. Such a lack in the awareness and understanding would be detrimental to educators’ pedagogical competency and well-being. The findings suggest the importance to raise the level of awareness and understanding of educators about tortious act and liability, regardless of their backgrounds and the institutions they represent by introducing a basic course in tort law in their vocational training by the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Higher Education respectively, either at the pre-service, in-service or post-service levels.

Conclusion

Educators should be aware of the tortuous liabilities in performing their duties. The educational policies, rules, regulations and legislations imposed upon educators in performing pedagogic activities of the institutions must be observed. They must be conversant with the relevant laws relating to education which govern the general and specific operations of the educational institutions. It is most crucial for educators to observe due diligence in discharging their duties and responsibilities towards their charges so as to prevent unnecessary tortious pitfalls.

Acknowledgments

This research is sponsored by the Multimedia University Malaysia.

References

- Abdul Hamid, M.I., & Nik Mohammad, N.A. (2016). Legal education and risk management for educators in Malaysia. Petaling Jaya, Malaysia: Lexis Nexis.

- Birch, I., & Richter, I. (1990). Comparative school law (1st. ed.). Oxford: Pergamon Press.

- Essex, N.L. (2012). School law and the public schools: A practical guide for educational leaders (5th ed.) Pearson.

- Fischer, L., Schimmel, D., & Stellman, L. (2012). Teachers and the law (8th ed.). United States: Pearson Edition.

- Furmston, M.P. (1986). The law of tort: Policies and trends in liability for damage to property and economic loss. Singapore: Singapore Management University.

- Imber, M., Geel, T.V, Blockkhuis, J.C., & Feldman, J. (2014). A teacher’s guide to education law. New York and London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Kaplin. W.A. (2013). The law of higher education (3rd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Oxford Dictionary of English. (2002). Great Britain: Oxford University Press.

- Ruff, A. (2005). Education law, text, cases and material. United States: Oxford University Press.

- Alsagoff, S.A. (2015). The law of torts in Malaysia. Petaling Jaya, Malaysia: LexisNexis.

- Tulasiewicz, W. & Strowbridge, G. (1994). Education and the law. London: Routledge.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 December 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-051-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

52

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-949

Subjects

Company, commercial law, competition law, Islamic law

Cite this article as:

Hamid, M. I. A., Mohammad, N. A. N., & Aziz, M. A. A. (2018). Legal Aspect Of Teaching: Eluding Tortious Act, Humanizing Pedagogical Competency. In A. Abdul Rahim, A. A. Rahman, H. Abdul Wahab, N. Yaacob, A. Munirah Mohamad, & A. Husna Mohd. Arshad (Eds.), Public Law Remedies In Government Procurement: Perspective From Malaysia, vol 52. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 35-50). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.12.03.4