Abstract

The Syria-Iraq war and the rise of the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) have strengthened extremists and their sympathizers across Southeast Asia to raise funds via few undetected channel. Along the same line, the non-profit organization fundraising activity has been reported widely in Malaysia and other regional countries. The capacity of Non-Profit Organisations (NPOs) to raise large amounts of undetected funds is highly vulnerable. Among the efforts taken by the Malaysian government in safeguarding NPOs is the targeted approach, educating the NPO’s sectors, increase controls on high-risk activities, centralized controls on Zakat and the effective regulatory controls (

Keywords: Law Enforcement AgenciesTerrorism FinancingNPO’s”Islamic CharitiesAnti-terrorism financing framework

Introduction

The crime of terrorism financing received numerous attention after the September 11 attacks in the US. Such crime is associated with destruction and giving other effects to the country such economy and stability of a nation (Yahaya, 2014). The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) 2008 reported that financing of terrorist is required to fund the operations, developing and maintaining a terrorist organization and also to create an enabling environment necessary to sustain their activities. With a small sum of money, the damage can be severe to the public property and even life (D’ Souza, 2012). Since the 2001 attacks, the vulnerability of NPOs to terrorism financing has spawned the concern around the globe including in Malaysia. Also, the recent Malaysian National Risk Assessment (NRA) Report 2014 indicates that that the crime of terrorist financing is posing a medium risk to the country. The literature suggests that such abuse of NPOs for terrorism financing are to some extent caused by the insufficient monitoring and laws in place by the regulators in ensuring the safety of NPOs against terrorism financing. As such, the primary objective of this paper is to examine the legal and regulatory framework in governing charities against terrorism funding in Malaysia. The first part of the article confers on the problem statement. The second part discusses the research question and the research of objectives of the paper. The third part presents the methodology. The fourth part which is the core of this paper emphasizes the preliminary findings of the research aiming at the peril posed by charities to in financing of terrorism and the challenges for the law enforcement agencies in regulating NPO’s. The final part the paper concludes the article.

Problem Statement

The literature available on the legal framework regulating charities against the threat of terrorism financing especially on NPO’s sector is rather scant. To date, there is a lack of research on the existing legal framework governing NPOs due to the nature of such organization which is secretive, despite their registration under the Societies Act 1966. The limited research on the NPOs sector and their threat to the financing of terrorism in Malaysia are required and overdue. This should be in line with the longevity and more recently breadth of financially-focused counter-terrorism policies in the Malaysia and international community’s strategic focus to eradicate terrorism and its financing parts. Despite the significant developments in targeting our adversary’s finances, till date, there is no methodologically rigorous examination exists about the financial war on the legal framework for charities.

Extant literature in the United Kingdom indicates that charities are one of the possible channels for a terrorist to raise fund. In the past, the Irish Northern Aid Committee (NORAID) had supported the Irish Republican Army (IRA) but was condensed under the Foreign Agent Regulation Act when it became convenience politically to do in the 1980s (Madinger, 2012). The Home Office and HM Treasury urge the Charity Commission to reinforce awareness of risk factors by the terrorist (Walker, 2011). In responding to the issue of terrorism financing, the Charity Commission had shown zero tolerance to the terrorist and had published a Counter Terrorism Strategy. The Commission had been proactive in monitoring and counter terrorism unit which forms part of the intensive casework unit in compliance and support as well issuing Operational Guidance.

Within Malaysia context, Section 14 of the Societies Act 1966 provides that all registered societies are required to submit annual returns to the ROS (Mohamed Zain, 2013). Such financial statement must include the balance sheet; the minutes of general meetings; the updated details of office bearers; the particulars of any amendments to the society’s rules; the specifics of any society or organization with which the society is affiliated or associated; and the details of any property or benefit received by the society (Best Practice Guides on Managing NPO’s, 2014). However, the accounts of such NPOs need to be submitted, and there is an exception for the audit, hence there is no check and balance which might lead to the abuse of the NPO. For instance, the BNM National Risk Assessment on Money Laundering and Terrorism Financing in 2014 notes that, as of the end of 2013, the rate of non-compliance with annual filings by the societies with the ROS were more than 49 per cent. Also, the National Risk Assessment 2014 further reported that there is a probability of that the NPOs which are not detailing organizations under the law are being exploited to encourage financing of terrorism (Bank Negara Malaysia, 2014). Likewise, the exclusion of NPOs within the ambit of AMLATFPUAA 2001 makes them susceptible to the risk of tax evasion and terrorism financing (The Dewan Negara Parliament Hansard, 2015). The 2015 FATF Mutual Evaluation Report on Malaysia reveals the country was generally in adherence to the Special Recommendation VIII, regardless of the intense on the crevices in the regulatory framework for disappointments by the NPOs with their commitment. Along the same line, the risk of the terrorist financing per due to the distinctions in the unequivocal record-keeping necessities by such substances (Zubair, Oseni & Mohd. Yasin, 2015). Also, the mutual evaluation report 2015 (FATF, 2015) indicates that the Malaysian AML/CFT administration is lacking in the record-holding commitment for NPO under the Societies Act 1966 which has not been enhanced since the last amendment in 2007. The Report likewise expressed that reliably focused on vulnerability data from the special Branch of the Royal Malaysian Police and further assets from the ROS are expected to restrained further dangers of terrorism financing abuse of NPOs. The 2015 FATF Mutual Evaluation Report additionally noticed that around 1,000 organization in Malaysia were included in global exchanges. Some of them which are foundations and religious NPOs have been recognized as being high risk. Along the same line, the Islamic charities and zakat are not within the mandate of the Central government since the religious matters in Malaysia is governed by the state authority (Mohamed Zain, 2013). The separation of powers had led to the impediments as how to track the money trails from charity.

Research Questions

Referring to the above problem statement, the research question that this paper would address the comprehensiveness of the legal and regulatory in securing NPOs against terrorist financing.

Purpose of the Study

This paper aims at filing in the lacuna in the local literature on the susceptibilities of NPOs and also to examine the legal and regulatory framework in Malaysia in securing NPOs against terrorist financing. Also this articles seeks to provide some preliminary evidence on the Malaysian legal terrain in regulating NPOs.

Research Methods

This research adopts a qualitative methodology. In gathering primary data, semi-structured interviews will be conducted with selected respondents according to their expertise and designations involving a total of nineteen respondents. The interviews was conducted in person and involved (4) four officers from the Commercial Crime and Counter-Terrorism Unit of the Royal Malaysian Police (RMP), (2) officers from Royal Malaysian Customs (RMC), (2) two officers from Eastern Sabah Security Command (ESSCOM), (2) two officers from Immigration Department, (2) two respondents from the Financial Intelligent and Enforcement Unit (FIU) of the Central Bank Malaysia, (1) one representative from Internal Security and Public Order Department in the Ministry of Home Affairs, (1) one representative from Ministry of Foreign Affairs, (2) two representatives from the defence counsels, (2) two Deputy Public Prosecutors (DPP) and one (1) representative from Department of Islamic Development Malaysia (JAKIM) will be chosen based on a purposive sampling technique. The purposes of the interviews are seeking information that is unavailable in the literature and to obtain various individual views and opinions on how the law enforcement agencies regulate the terrorism financing investigation and what are the issues and challenges comprises. As for the collection of secondary data, the research conducted is library-based, where there is a need to examine the primary sources involving the provisions of all the laws mentioned above in the Malaysia, and the UK. The research will also be supported by referring to other secondary sources such as the Hansard, textbooks, articles in academic journals, international and local reports, working papers, case laws, online sources, and an online database such as Emerald, Hein Online, and Sage Publication Online.

Once all the relevant primary data has been gathered from the sources, such data will be transcribed and later on, analysed using the content analysis method and Atlas.Ti software, in which the law and the available texts will be examined to see how they will relate to each other. Finally, the comparison made to the terrorism financing investigation position in the United Kingdom is only via the literature that is legislation and not by conducting any fieldwork in the UK.

In phase two, the primary data was generated by adopting an exploratory research design, involving nineteen stakeholders from Klang Valley and Sabah which involves the representatives from the law enforcement agencies, FIUs and the Deputy Public Prosecutors. The instrument for the interview was the face-to-face semi-structured interviews.

Qualitative data analysis was conducted through thematic and content analyses, in which the perceptions and the meeting transcripts from the semi-structured interview were inspected. The procedure comprised of making codes and themes, considering the topics and afterward making hypothesis about the respondents' encounters, alongside the combination of expert’s suppositions on the issues and the writing survey (Silverman, 2013). The essential information was triangulated with the semi-structured interview data obtained from the law enforcement agencies, FIU, DPP and Religious authority. The meetings have been carefully recorded and their substance have been interpreted and examined utilizing the Atlas.Ti subjective research programming.

Findings

The research findings are divided into two phase. The first phase analyse the literature available in the secondary data using the content analysis approach. The second phase of finding sensitizing from the analytical framework approaches research design.

Findings on Phase One: The Peril of Charities in Financing of Terrorism

The existence of a government depends on its ability to create and maintain peaceful order within a society (Leong, 2007). The available literature indicates that countries should ensure that their legal framework does not impede the usage of multidisciplinary groups (FATF, 2012). The FATF Recommendation in 2012 suggests that there should be designated law enforcement authorities to oversee and monitor money laundering, predicate offenses and terrorist financing are properly investigated through the conduct of a financial investigation (FATF, 2013). The FATF 40 Recommendations urges all countries to establish mechanisms which allow financial investigators to obtain and share information among the law enforcement agencies. Also, it was further suggested that there must be mechanisms for investigators to use their powers to assist foreign financial investigations and also be allowed to establish and utilize joint investigative teams with law enforcement in other countries (Dhillon, et. al, 2013). The co-operation can be done through bilateral and multilateral arrangements, such as the memorandum of understanding (MoUs) (Walker, 2011). The financial investigators are encouraged to strategically include cooperation with non-counterparts as part of financial investigations, indirectly or directly. The information received from other countries for investigative and law enforcement purposes must protect from unauthorized disclosure. Furthermore, the FATF 2012 Recommendation suggests that states must establish procedures to allow informal exchanges of information to take place before the submission of a formal request); in essence, advocating the exhausting of all forms of informal cooperation prior to the submission of a mutual legal assistance (MLA) request.

In relation to funding of terrorism, such crime came to light after the September 11 attacks. The US government had prioritized waging war against the financing of terrorist groups, including funds raised by terrorist activities channelled through non-profit organizations (Bell, 2007). The US government in 2002 had seized $7.3 million from the charities that were believed to be linked to al-Qaeda or other terrorist organizations, and $5.7 million was frozen internationally by countries concerned that “spurious charitable organizations” were functioning within their borders (Bell, 2007). Ryder (2015) contends that the Al Qaeda group received approximately 30% of its financial resources from donations solicited in the United States and abroad. Furthermore, he reported that until September 2006, the Treasury Department of US had identified 43 charities worldwide and 29 associated individuals as Specially Designated Nationals (“SDN”) for their support of terrorist organizations and operations (Ryder, 2015). Most of the abuse of charities were linked to religious-based funding. The lack of accountability for government and asset blocking actions, limited independent review that has taken place reveals cause for concern and highlights the need for more robust oversight and due process protections for charities (Glaser, 2010).

Referring to the United Kingdom law, such country has turned into a consistent abstain that cash is a crucial factor in the terrorism. Enactment against the funding of Irish and worldwide terrorism has prospered in recent decades, with consideration regarding jihadi terrorism financing merely strengthening settled strategies. There were likewise new measures to broaden the extent of investigative and freezing powers, account monitoring and customer information orders. Freezing powers are additionally governed by the Counter-Terrorism Act 2008, Part V. All the more as of late, prosecution about universal approvals has created the Al-Qaida and Taliban (Asset-Freezing) Regulations 2010 and the Terrorist Asset-Freezing and so forth (Walker, 2011). It will be found that the impact of policing is very uneven, an outcome which raises doubts about the strategies being deployed and whether different tactics might be more suitable. The peril in charitable financing is elevated by two factors. One is the Islamic legal tax, of zakat which is the religious obligation to give an extent of one's wealth for fulfilling the religious obligation purposes (Walker, 2011). The second factor identifies with those foundations which are active in regions of conflict (for example, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Palestine, Somalia and, up to this point, Sri Lanka) and are thereby especially vulnerable to being compromised by the unavoidability of working alongside protagonists within the conflict. These delineations of the political and lawful remarkable quality of the personal integrity of charity workers who view their independence from terrorism and government as crucial to their work and the individual honesty of philanthropy who see their autonomy from terrorism and government as vital to their work. The affirmations of complicity in terrorism likewise embellish the relationship to criminal racketeering or more generally to rational choice theory (Walker, 2011).

In Malaysia, despite being rated as medium risk by Australian government (AUSTRAC Report, 2016) for their risk against terrorism financing and the abuse of local NPOs and charities, there are still some websites pleading for donations to help poor Muslim families or to support the Palestinian could be used as a device for terrorist groups in raising funds to support families of terrorists left behind in Malaysia or for financing suicide attacks in Syria, Iraq or other parts of the world (Foo, 2016). Terrorist groups had utilized Internet’s relative to solicit online donations easily from both supporters and unsuspecting donors of charitable activities (Hamin, Selamat & Othman, 2014). The use of the sympathy to gain the public trust in raising funds is one of the common modus operandi. They disguise their fundraising as a charity for the sustenance of poor Muslim families. Furthermore, in order to mask their fundraising activities, the collection was transferred via banks in very small amounts to avoid raising the suspicions of the authorities. The police had detected Rakyat Malaysia Bersama Negara Islam and RevolusiIslam.com are among the websites being used as channels to raise funds despite other social sites used to raise funds According to the police, the person who donates the money might come from the middle-class people who are being influenced by these radical groups (Foo, 2016). There are numbers of Malaysians who were donating, thinking it is for a good cause, but the money was instead being used to fund attacks all over the world. Likewise, the southern parts of the Philippines, in Mindanao, were being turned into centre to recruit terrorists (Tan, 2007). In order to mask their illegal activities of in supporting terrorism, they use Telegram chats which have encrypted services, making it difficult for law enforcers to access information. The most common practice to transfer the money is by using the small amounts of money (Gunaratna, 2016).

Terrorist raise funds through different channels and send small amounts. Furthermore, it is suggested that the bankers keep track of the small amounts of money being transferred frequently to the same bank accounts and also to look out for identity thefts. These are difficult transfers to trace. But if money is being sent to remote places, where terrorism acts are reported, bankers should keep track of this (Shipley, 2016). Shipley said the Department of Justice in the United States had noted the increasing number of identity thefts from social media, making it difficult to trace the people behind the recruiting of members, raising funds and organising attacks. The financial institutions must have an easy access to information on customers. In the US, the authorities could email or fax the relevant authorities for information to check on criminal activities and credit card or other statements of the client. Quick access to information about a suspected individual helps in any investigation or to keep track of the clients. Among another effort by the Malaysian government are, Malaysian police have detained more than 200 individuals, including 27 foreigners, for suspected links with terror groups. In 2015, Malaysian authorities revoked the passports of 68 citizens who were identified as leaving the country to join Islamic State. The authorities believe more than 110 Malaysians have left for Syria in 2013 to join IS and 21 were confirmed to have been killed there. Eight have returned and are undergoing rehabilitation. There were families who sent their sons to do medicine in London, but these students later turned into Islamic radicals and even volunteered for suicide attacks.

Findings on Stage Two:

Awareness of the Abuse of Charities for Financing of Terrorism by Law Enforcement Agencies

The finding reveal that indeed the law enforcement were aware that the NPOs and charities in Malaysia are vulnerable for the crime of terrorism financing. Recognising the risk posed by the NPOs, the law enforcement agencies have adopted a close monitoring on the NPOS and close watch up on the fund raising activity by the humanitarian cause. Also, the monitoring process has also been extended on the internet and social media. On that issue, an officer from the law enforcement agencies uttered that:

…there is evidence that the terrorist group posting in the social media to raise fund for their charities and humanitarian purposes. It is our duties to make sure that the online posts which require donation came from the legitimate organization listing under the Societies Act 1966. In this aspect, few suspects were detained who had managed to raise funds through social media. In fact, some of them had been charged in the court.

Similarly, one respondents from the Attorney General Department confirmed the above facts:

Indeed there was the abuse of charities and NPOs using the medium of technology and social media…we had managed to charge a suspect for terrorist financing in the court based on several charges. Some of the charges are concerning on the raising money by using the name of charities via social media

Also, on the same issues, one respondent from the Islamic Religious Council which represents Islamic charities and NGOs in Malaysia confirmed that indeed there was a funding of terrorism activity using the name of Islam and the misconception of Jihad:

There are some of our Malaysians who are willingly helping or contributing some money to some extremist Islamic organizations without the knowledge that it is indirectly funding of some terrorism activities. The Muslim donor claims that it is part of their obligation in paying zakat and it is something done in fulfilment of religious obligation

The overall finding indicates indeed that the law enforcement agency are aware on the susceptibilities of the NPOs against funding of terrorism. However, the counter measures that was suggested is to take a more vigilant approach against any abuse of charities or NPOs for such crime. The evidence also further suggested that the funding of terrorism activities do have some connections with the religious based charities in Malaysia and it will lead to some misconceptions among the believers. Such finding confirmed the Foo (2016) and Mohamed Zain (2013) which stated that indeed NPOs are vulnerable to the funding of terrorism and the awareness level of the law enforcement agencies. The evidence suggest that from the recent case of ISIL-related financing risks evolved in 2015, and Malaysia has yet to plans the update of most recent NRA to include further assessment of terrorist finance risks. Malaysia does not oblige non-profit organizations to file STRs, but they are required to file annual financial reports to the Registrar of Societies (ROS), which may file such reports. Law enforcement works with the ROS and other charity regulators to prevent the threat of terrorism financing in the NPO sector, especially in susceptible areas like religious or charitable NPOs. For the training purposes, the ROS also conducts an annual conference for its members on the risks of terrorism financing.

Challenges in Policing NPOs against Terrorism Funding

The finding also revealed that there are many challenges faced by the law enforcement agencies in detecting and investigating the abuse of charities within the NPOs sector. As stated by one of the law enforcement agency:

…we are acting in accordance with the law. The fund raising through charities is very difficult to trace and make it difficult for us to prevent such abuse. This present challenge for the law enforcement officers to track down the abuse. To overcome this, we will need to strengthened cooperation and coordination among national agencies, particularly intelligence agencies and financial intelligence units (FIU).

The officer further stated that:

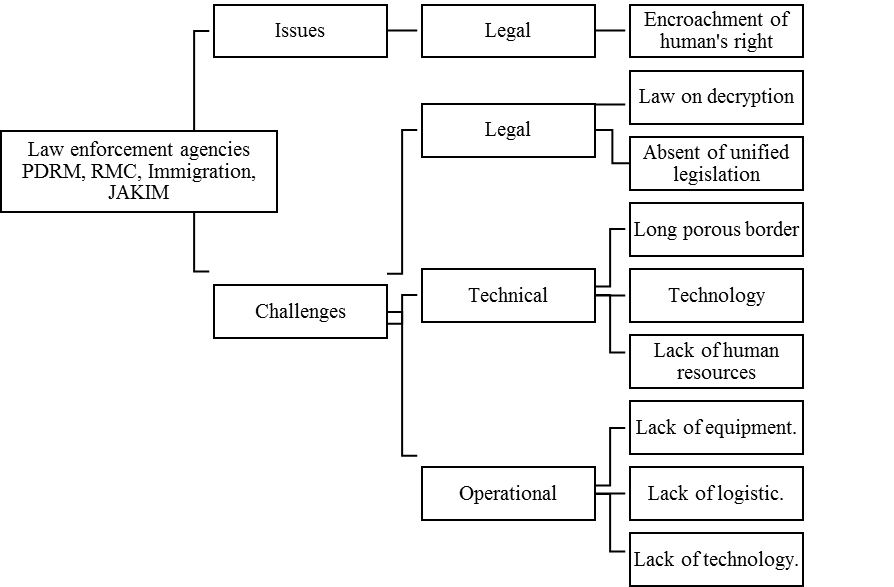

…the challenges that we have identified could arise from the legal and technical aspect. From the legal perspective, the challenges could come from the applicable law, guidelines available in investigating such abuse... Meanwhile for the technical would be the advancement of forensic tools and investigation aspects available to conduct investigations

The triangulation of the data between the law enforcement agencies and the regulators indicates that the awareness on the susceptibilities of NPOs against terrorism funding are rather satisfactory. However, despite of the awareness, the challenges persists in policing the charities from being abuse against terrorism financing as there is lacunae in Malaysia legislation as to the exclusion of the NPO’s in the AMLATFPUAA 2001. Apart from the exclusion within the ambit of anti-money laundering and anti-terrorism financing, the challenges in eradicating the abuse of NPOs is also in identifying the donor which remains confidential and the bedrock of charities organization. Such finding confirmed the official FATF 2015 report and Hamin, Selamat and Othman (2015) which stated that indeed NPOs are vulnerable to the funding of terrorism and the awareness level of the law enforcement agencies.

Conclusion

The legal and regulatory measures for Malaysia regulating the NPOs from the peril of terrorism financing are in line with global Conventions and the FATF measures. The legal framework in Malaysia are wide-ranging in governing the terrorism financing but not comprehensive in regulating the charities as it involves multiple level of administration (Zubair, Oseni & Mohd. Yasin, 2015). While terrorism financing was not considered as a high risk in Malaysia’s according to the National Risk Assessment (NRA) 2014, the continued influence of ISIL suggests that threat may be increasing, in particular, a small but growing number of terrorists have sought to raise funds through charities for their family, friends, and the internet to support their travel to fight with ISIL (Bank Negara Malaysia, 2015). Apart from the existing legislation, there is a lot of issue compounded in governing the NPO. The absence of any unified system of regulatory oversight in the cast of the Charity Commission in the United Kingdom hypothetically expose the NPO sector to terrorism financing. The fact that the regulation of the zakat institutions cannot be standardized when they are being administered by the different State Islamic Councils with their own rules and regulations. The main question that will popped out is, can the legislations and the regulators of the NPOs in Malaysia balance the need to prevent the NPOs from being the channels of terrorism financing and the interests of the NPOs in promoting their charitable and humanitarian efforts.

References

- AUSTRAC Report. (2016). on Asia and Australia http://www.austrac.gov.au/about-us/international-engagement/counter-terrorism-financing-summit. Retrieved on 26 Mac 2017.

- Ahmad Nadzri, F.A., Abd Rahman, R. and Omar, N. (2012). Zakat and Poverty Alleviation: Roles of Zakat Institutions in Malaysia. 1(7) International Journal of Arts and Commerce 61.

- Bank Negara Malaysia. (2014). Anti-Money Laundering, Anti-Terrorism Financing and Proceeds of Unlawful Activities Act 2001 (Act 613). Retrieved from http://www.bnm.gov.my/ on 26 April 2017.

- Bell, J. L. (2007). Terrorist Abuse of Non-Profit and Charities: A Proactive Approach to Preventing Terrorist Financing. Kan. JL & Pub. Pol'y, 17, 450.

- Best Practice Guides on Managing NPO. (2014). Legal Affairs Division, Prime Ministers Department, Companies Commission of Malaysia (CCM), Registrar of Societies of Malaysia (ROS), Labuan Financial Services Authority (Labuan FSA) and Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM), <http://www.bheuu.gov.my/portal/pdf/Akta/141106_NPO%20Best%20Practices.pdf> accessed 15 April 2017.

- D’ Souza, J. (2012). Terrorist Financing, Money Laundering and Tax Evasion; Examining the Performance of the Financial Intelligence. London: Units CRC Press.

- Dhillon G., Ahmad R., Rahman A., Ng. (2013). The Viability of Enforcement Mechanisms under Money Laundering and Anti-Terrorism Offences in Malaysia. Journal of Money Laundering Control, Vol. 16. Retrieved from http://www.dx.Doi.Org/10.1108/13685201311318511 on 27 June 2017.

- Financial Action Task Force (FATF). (2008). The FATF Recommendations. Retrieved from http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/ on 26 January 2017.

- Financial Action Task Force (FATF). (2012). the FATF Report Operational Issues Financial Investigations Guidance. The FATF Recommendations. Retrieved from http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/ on 26 January 2017.

- Financial Action Task Force (FATF). (2013). International Standards on Combating Money Laundering And The Financing Of Terrorism & Proliferation- The FATF Recommendations. Retrieved from http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/ on 26 January 2017.

- Financial Action Task Force (FATF). (2015). Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Measures. Retrieved from http://www.apgml.org/mutual-evaluations/documents/default.aspx on 26 January 2017.

- Foo, W. M. (2016). Responding to Terrorism Financing Risks: Trends and Insights from Across the Region. Plenary Session 5 at the International Conference on Financial Crime and Terrorism Financing IFCTF 2016. The Majestic Hotel, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

- Glaser, D. L. (2010) Oversight, U.S. Department of the Treasury before the House Committee on Financial Services. Anti-Money Laundering: Blocking Terrorist Financing And Its Impact On Lawful Charities: Hearing before the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations of the Committee on Financial Services, U.S. House of Representatives, One Hundred Eleventh Congress, second session, May 26, 2010: U.S. G.P.O.

- Gunaratna, R. (2016). Responding to Terrorism Financing Risks: Trends and Insights from Across the Region. Plenary Session 5 at the International Conference on Financial Crime and Terrorism Financing IFCTF 2016. The Majestic, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

- Hamin, Z., Selamat, H., Othman, R. (2014). Conceptualizing Terrorism Financing in the Age of Insecurity. Paper presented at International Conference on Law, Order and Criminal Justice (ICLOCJ) 2014 19-20 November 2014, Kuala Lumpur.

- Hamin, Z., Selamat H., Othman R., (2015). Catch Me if You Can The Role of Financial Action Task Force (FATF) In Guiding Terrorism Financing Investigation. Paper presented at 4th International Conference on Law and Society 2015. 10-11 May 2015, University Sultan Zainal Abidin Terengganu Malaysia.

- Leong, A. (2007). The Disruption of International Organised Crime: An Analysis of Legal and Non-Legal Strategies. Aldershot, Hants, England: Ashgate.

- Madinger, J. (2012). Money Laundering. A Guide for Criminal Investigators. New York: CRC Press.

- Mohamed Zain, A. (2013). ‘Towards Better Governance of Non Profit Organizations (NPOs) in Malaysia’ (Conference on New Development of Anti Money Laundering & Counter Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT): Understanding the Roles of NPO, Renaissance Hotel, Kuala Lumpur, 14 November 2013).

- Ryder, N. (2015). The financial war on terrorism: A review of counter-terrorist financing strategies since 2001. Routledge.

- Silverman, D. (2013). Doing Qualitative Research, Third Edition, Sage Publication Inc. Great Britain.

- Shipley, J. (2016). Keynote Closing Address – An International Perspective on Trends in Financial Crimes and Terrorism Financing at the International Conference on Financial Crime and Terrorism Financing IFCTF 2016. The Majestic, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

- Tan, T. (2007). Terrorism and Insurgency in Southeast Asia. A Handbook of Terrorism and Insurgency in Southeast Asia. Great Britain. Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc. p. 5.

- The Dewan Negara Parliament Hansard. (2015). Retrieved from www.parlimen.gov.my/hansard-dewan-rakyat.html?uweb on 26 September 2017.

- Walker, C. (2011). Terrorism and the Law. Oxford: University Press, 2011. ISBN 13: 978-0-19-956117-9 & ISBN10: 0-19-956117-6, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- Yahaya, A.H.A. (2014). Assistant Governor’s Speech at the International Conference on Financial Crime and Terrorism Financing (IFCTF) 2014. International Conference on Financial Crime and Terrorism Financing IFCTF, 2014 Istana Hotel, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

- Zubair, A., Umar A. Oseni and Mohd. Yasin, N. (2015). Anti-terrorism Financing Laws in Malaysia: Current Trends and Developments. 23(1) IIUM Law Journal 153.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 December 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-051-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

52

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-949

Subjects

Company, commercial law, competition law, Islamic law

Cite this article as:

Selamat, H. S., & Kamaruddin, S. (2018). The Preliminary Evidence Of The Exploitation Of Non-Profit Organisations For Terrorist Financing. In A. Abdul Rahim, A. A. Rahman, H. Abdul Wahab, N. Yaacob, A. Munirah Mohamad, & A. Husna Mohd. Arshad (Eds.), Public Law Remedies In Government Procurement: Perspective From Malaysia, vol 52. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 280-290). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.12.03.27