A Study On The Validation Of The Drinking And Abstaining Behaviors Questionnaire Among Portuguese University Students

Abstract

Alcohol consumption among university students could be influenced by personal and environmental factors, where perceptions of behaviors are approved/disapproved and typically complied could be related to alcohol consumption. Considering the need to provide valid tools assessing descriptive/injunctive norms of drinking, our research question was: “What are the psychometric properties of the Drinking and Abstaining Behaviors Questionnaire (DABQ)?” We aimed to translate, cultural adapt and analyze the reliability and the construct validity of the Descriptive and Injunctive Norms of the DABQ (DN and IN) using 3 reference groups (Typical college students, Acquaintances and Good friends, to Portuguese university students. A validation, cross-sectional study was performed. The sample comprised 338 students (51.8% male), with a mean age of 20.6 years (SD= 3.4) from University of Aveiro, Portugal. To examine the factor structure of the Portuguese version, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed. Additionally, the internal consistency and convergent validity were also evaluated. Concerning the factor structure, the two-factor original model presented a better relative fit considering the DN in the three reference groups. For the IN, a modified two-factor model, showed a better relative fit to data considering the friends and closest friends. A satisfactory internal consistency was also found (.765<DN α<.891 and .675<IN α<.869). Our findings suggested DABQ is a valid tool in higher education settings. However, its factor structure should be (re)examined using CFA procedures within community samples.

Keywords: Drinking behaviorcollegesocial norms

Introduction

Alcohol consumption is frequent among university students (O’Malley & Johnston, 2002) and it is influenced by personal factors (social identity and the beginning of autonomy and independence) and environmental factors (peer pressure and favorable environment to alcohol consumption). This consumption could lead to several different problems, such as psychosocial problems (violence/aggression and sexual risky behaviors), legal problems, academic impairment and/or academic drop out, and increased morbidity and mortality related to alcohol consumption (Cooke, Sniehotta, & Schuz, 2006; Dotson, Dunn, & Bowers, 2015; Hagger, Wong, & Davey, 2015).

From a European perspective, a study in a Welsh university (UK) OF 367 students, found a moderate alcohol consumption proportion of 56.3% and a binge-drinking proportion of 18.3% (John & Alwyn, 2014). In Portugal, according to the General Directorate for Intervention on Addictive Behaviors and Dependencies (SICAD, 2015), a prevalence of 61% of regular alcohol consumption in young adult population was verified.

In university students, alcohol consumption is associated with gender (Eisenberg, Golberstein, & Whitlock, 2014; Gebreslassie, Feleke, & Melese, 2013; Schuckit et al., 2016), age (Gasparotto, Fantineli, & Campos, 2015; Primack et al., 2012; Schuckit et al., 2016; Silva & Petroski, 2012) and previous substances consumption like marijuana (El Ansari, Vallentin-Holbech, & Stock, 2014; Kraemer, McLeish, & O’Bryan, 2015; Schuckit et al., 2016). Moreover, the transition between high school and university represents a phase where there is a propensity for increased exploration of identity, the need of establishing a sense of belonging (McGloin, Sullivan, & Thomas, 2014; Scott-Sheldon, Carey, Elliott, Garey, & Carey, 2014), the enlargement of the students’ social network, the adhering to new social groups and participating in collective events where alcohol could be present (O’Malley & Johnston, 2002; Reed, McCabe, Lange, Clapp, & Shillington, 2010).

In addition to the factors associated with alcohol consumption and the academic environmental characteristics, alcohol consumption could be explained by the role of social norms. It is important to explain the etiology of these factors in university students (Perkins, 2002), where consumption between peers, as coping mechanisms, stress, positive expectations of the effects of alcohol, belief that their social network has a positive acceptance about drinking (injunctive norms) and personal belief that their social network presents high levels of consumption (descriptive norms) (Schuckit et al., 2016) could be related to this behavior. Furthermore, it has been found that university students tend to overestimate the alcohol consumption of their peers (descriptive norms) and consequently increase their own consumption (Borsari & Carey, 2003).

On the other hand, injunctive norms (that include social approval or social sanctions due to certain behavior), expectations (belief that one action might generate the benefit expected by the individual) and groups’ identity (affinity that the individual perceives with his reference group) moderate the relationship between the descriptive norms and consumption behaviors (Rimal, 2008).

Problem Statement

Descriptive norms have been consistently associated with drinking in university students (Reid & Carey, 2015). However, there are inconsistencies in the role of injunctive norms with drinking behaviors, regarding proximal (e.g. friends) and distal reference groups (e.g. typical students), suggesting that injunctive norms are more complex than descriptive norms (Carey, Borsari, Carey, & Maisto, 2006; Neighbors et al., 2008).

In this context, the Drinking and Abstaining Behaviors Questionnaire, developed by Meisel, Colder and Read (2016), sought to advance the assessment of injunctive norms by developing a new measure that evaluated a varied range of drinking behaviors from abstaining from drinking to alcohol-related consequences. Likewise, the same behaviors for the assessment of descriptive norms to enable the comparison of the predictive utility for each type of norm were included.

Research Questions

Considering the need to provide valid tools to assess descriptive/injunctive norms of drinking, our research question was: “What are the psychometric properties of the Drinking and Abstaining Behaviors Questionnaire (DABQ)?”

Purpose of the Study

In this study, we aim to translate, to cultural adapt and to analyze the reliability and the construct validity of the Descriptive and Injunctive Norms of Drinking and Abstaining Behaviors Questionnaire (DN and IN DABQ), considering a sample of Portuguese university students.

Research Methods

Participants and Procedures

A validation study with data collected by a cross-sectional method was performed. The sample comprised graduate students from the University of Aveiro, Portugal, during the academic year of 2016/2017. The inclusion criteria were: i) aged between 18 and 27 years old, due to the fact it represents the first and second transformation stages of the young adult, when they build their own identity, autonomy and life goals (Hoffman, Paris, & Man, 1994) and ii) being a graduate student.

Through a convenience sampling, a 400 student sample was gathered during the period from February to May of 2017. Of these, those questionnaires that had missing answers (which were important to be assessed in order to respond to the objective) were excluded, obtaining a total of 338 students with valid returned questionnaires. 51.8% male students constituted the sample, with a mean age of 20.6 years (SD 3.4) and a proportion of alcohol consumption of 65.9% (n = 213) was identified.

The data collected and analyzed in the present paper are part of a doctoral thesis which was considered by the Scientific Commission of the Education Doctoral Program of the Education and Psychology Department of the University of Aveiro, Portugal, and given a favorable review. All participants provided written informed consent and the ethical principles of anonymity, confidentiality, voluntary involvement of the research participants, beneficence, non-maleficence and justice were considered (Bryman, 2012); Permission was requested from the authors who developed the DN-DABQ and IN-DABQ (Meisel et al., 2016) and the Portuguese version of the Drinking Motives Questionnaire – Revised (DMQ-R) (Fernandes-Jesus et al., 2016), to apply the instruments in the present study.

Measures

Data was collected using a self-reported questionnaire. The questionnaire comprised sociodemographic variables, drinking motives (DMQ-R) and drinking and abstaining behaviors (DABQ) related variables.

The DMQ, originally developed by Copper (1994), and after validation in 6 European countries (including Portugal) (Fernandes-Jesus et al., 2016), comprises 4 factors, with an internal consistency, measured by Cronbach’s alpha, of 0.944, 0.861, 0.783 and 0.918 respectively for Enhancement, Coping, Conformity and Social drinking motives. In this questionnaire, students are required to report to what extent for each item, their drinking behavior was motivated, using a five-point Likert scale, proposed by Cooper (1994), ranging from 1 (almost never or never) to 5 (almost always or always).

As for the DN-DABQ and the IN-DABQ, developed by Meisel et al. (2016), an exploratory factor analysis indicated a 2-factor model for the DN-DABQ (with factor loadings > 0.32 for both factors), and 3-factor model of the IN-DABQ (with factor loadings >0.32 for all factors), with 13 items each.

Both questionnaires were developed in order to reflect a range of drinking behaviors and reasons for abstaining from drinking for 3 reference groups (Typical college student, Acquaintance and Good friend) [The processes of development of both questionnaires can be found in Meisel et al. (2016)].

The process of translation and cultural adaptation to Portuguese of DN-DABQ and the IN-DABQ was performed as described by the guidelines (World Health Organization, 2017): i) forward translation; ii) expert panel back-translation; iii) pre-testing and cognitive interviewing and iv) final version.

The pre-testing and cognitive interviewing were performed through a convenience sample, collected from the study population. The questionnaire was applied to a sample of 19 students, with a mean age of 22.7 years old (SD: 3.0). It took a mean of 16.5 minutes (SD: 3.9) to complete the questionnaire. Furthermore, after completing the questionnaire, a cognitive interview was performed through semi-structured interviews in agreement with Bryman (2012), where students were asked about their comprehension and what could be enhanced in the questionnaire to better understand it. After the pre-test and the interviews, all needed changes in translation and cultural terms were made.

For the DN-DABQ, participants were instructed to select the number of times a reference group engaged in each behavior (7 items) and reason for abstaining (6 items). For the IN-DABQ, students rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disapprove) to 7 (strongly approve) the extent to which a reference group approved the same reasons for drinking behaviors and reasons for abstaining.

Data analysis

A Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted to examine the factor structure of the Portuguese version of the questionnaire within the 3 reference groups (Typical college student, Acquaintance and Good friend) through MPlus, version 6.12. Given the categorical nature of the measure, Weighted Least Squares with Mean and Variance Adjustment (WLSMV) was used (DiStefano & Morgan, 2014). As recommended by Hu and Bentler (1999) the cut-off criteria were: a non-significant χ² statistic; the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) <0.006 and the comparative fit index (CFI) >0.95. The Weighted Root Mean Square Residual (WRMR) generated by MPlus was also included, indicating the weighted difference between the sample and population covariance. The cut-off criteria for this index fit was WRMR <1.00 (Schreiber, Nora, Stage, Barlow, & King, 2006).

To examine the reliability of the measure, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients and inter-item correlations were determined.

Concerning convergent validity analysis, hierarchical multiple regression models were performed, adjusting for age, gender and smoking habits (categorical variable). Collinearity diagnostics were assessed. To verify for autocorrelation in the residuals from a statistical regression analysis, the Durbin Watson statistics were performed for all models.

All models included in block 1 covariates (age, gender and smoking habits), where smoking habits were included as covariate because the association with higher levels of drinking behaviors (Harrison, Hinson, & McKee, 2009; King & Chassin, 2007) has been established. The factors from DN and IN drinking behaviors and reasons for abstaining from drinking were included in block 2. Zero-order correlations between the covariates and the scores from the DN and IN were assessed.

Findings

Factorial Validity of the Norms Measures

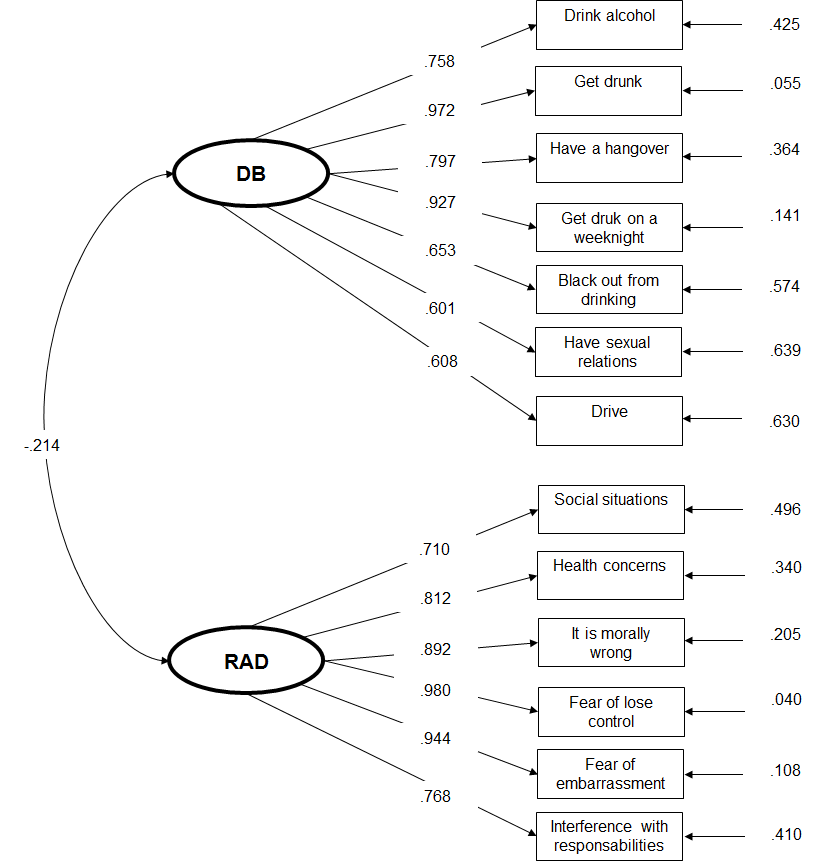

Using a Portuguese university students’ sample, this structure presented an acceptable fit for the typical college student reference group. For this group, the model passed two of the four criteria as displayed in Table

The two-factor solution used to DN-DAB was also explored. Although, this model was more parsimonious, the fit to data was worse than in the first model. An examination of the factor loadings suggested that the “drink alcohol” item presented a lower load (ranging from 0.274 to 0.383) compared with other indicators variables within the DB latent factor.

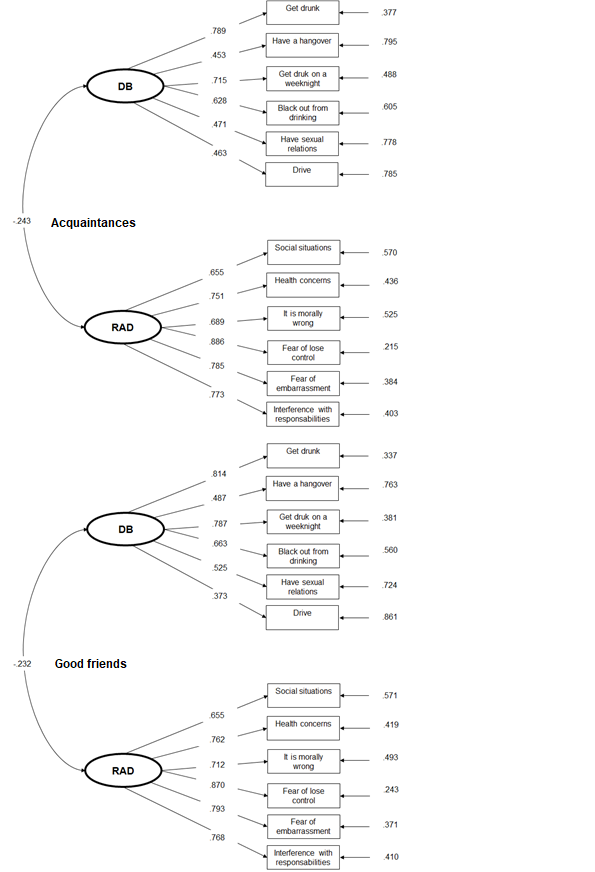

Thus, a modified two-factor excluding this item provided a better relative fit in comparison with three-factor original model for acquaintances and good friends’ reference groups (see figure

Reliability analysis

Observing the Cronbach’s alpha if items were deleted, in the DB factor, the items “Drink alcohol” and “Drive” presented a value higher than the Cronbach’s alpha of the factor for the referents Acquaintances (0.826 and 0.829 respectively) and Good friends (0.789 and 0.782 respectively). Also, in the RAD factor, the item “social situations” presented a higher value than the Cronbach’s alpha of the factor for the referents Typical Students (0.866), Acquaintances (0.883) and Good friends (0.880). Concerning the inter-item correlations, for the referent group Typical students, these ranged between 0.374 to 0.795 and 0.315 to 0.849 (DB and RAD factors respectively); Acquaintances between 0.205 to 0.827 and 0.316 to 0.853 (DB and RAD factors respectively); and Good friends between 0.042 to 0.724 and 0.378 to 0.787 (DB and RAD factors respectively).

By observing Cronbach’s alpha if items were deleted, it was verified in the DB factor that the item “Drive” presented a value higher than the Cronbach’s alpha of the factor for the referent Acquaintances (0.678) and Good friends (0.702). Inter-item correlations ranged between 0.168 to 0.675 (DB) and 0.424 to 0.734 (RAD) for Typical students, between 0.103 to 0.622 (DB) and 0.405 to 0.686 RAD) for Acquaintances, and between 0.047 to 0.675 (DB) and 0.413 to 0.683 (RAD) for Good friends.

Convergent validity

To analyze the convergent validity, zero-order correlations between the covariates and scores from the DN and IN factors were calculated (table

Smoking was significantly associated with enhancement drinking motives across referents (Typical students, Acquaintances and Good friends). Age was associated across the different referents on coping, conformity and social drinking motives, where the higher the levels of drinking motives the lower the age of the students. Gender was associated across the different referents on conformity and social drinking motives, where higher levels of drinking motives were associated with male students.

Concerning descriptive norms, for typical college students, a significant association was found between DB with social drinking motives. For RAD, associations were observed with enhancement and social drinking motives. For the Acquaintances’ reference group, an association was observed between RAD with social drinking motives. As for Good friends, associations were verified between DB with enhancement and coping drinking motives.

Regarding injunctive norms, drinking behaviors for both Acquaintances and Good friends were consistently associated with all drinking motives factors (enhancement, coping, conformity and social).

Discussion

A translation and cultural adaption to Portuguese of the Descriptive and Injunctive Norms Drinking and Abstaining Behaviors Questionnaire was accomplished in this study. The study also aimed to analyze the factorial structure, internal consistency and convergent validity where an acceptable fit for DN and IN factorial model were observed. The Portuguese version presented satisfactory psychometric proprieties compared to the original version.

When we examined the factor structure, the two-factor original model (DB and RAD latent factors) presented a better relative fit considering the descriptive norms in the three reference groups. Although the models did not pass in all cut-off criteria, alternative solutions conceptually justified was not found to be well-fitting to the data. A three-factor solution separating drinking behaviors and their consequences was tested, but the high association between these latent factors indicated its non-independence in construct modeling.

So, after the CFA, a model for the questionnaire was obtained, composed of a first factor, about Drinking Behavior including 7 items and 6 items referring to the Reasons for Abstaining from Drinking factor, for the 3 reference groups (Typical college student, Acquaintances and Good friends).

Neighbors et al. (2008) verified that the influence of injunctive norms and drinking varied as a function of the reference groups. These findings could corroborate the three-factor original structure, that presented an acceptable fit to the Typical college student reference group. However, the modified two-factor model excluding the “drink alcohol” item, showed a better relative fit to data considering Acquaintances and Good friends’ reference groups.

The exclusion of “drink alcohol” item could be explained with what was verified in the original study, where it was verified that RAD was positively associated with “drink alcohol” for Typical students, but negatively associated for Acquaintances and Good friends reference groups. For these associations, the authors suggest that the relationship between injunctive norms for RAD with alcohol use may differ as a function of the reference groups (Meisel et al., 2016). Additionally, the difference between the original model and the modified two-factor model, by excluding “drink alcohol” on IN drinking behaviors could be attributable to the variation of the relationship between perceived injunctive norms and drinking with the proximity of the reference group (Neighbors et al., 2008).

In this context, a different factor structure was also verified between DN and IN in the original study, possibly due to the complex influence of IN on drinking behaviors (Meisel et al., 2016). By definition, descriptive norms are concerned with the environment (what most others do), while injunctive norms impose behavioral guidelines (what most others approve or disapprove) (Cialdini, Reno, & Kallgren, 1990), where the injunctive norms exercise a direct influence on behavioral intention, but do not interact with descriptive norms (Rimal & Real, 2005). Both injunctive and descriptive norms affect consumption only after social networks have been more firmly established (Rimal & Real, 2005). This fact could explain the different factor structure verified among DN and IN in our sample, where the students had to answer according to the different reference groups (Typical students, Acquaintances and Good friends). Also, the difference observed is possible due to the inconsistent findings related to injunctive norms and drinking behaviors (Krieger et al., 2016).

Regarding the internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha ranged between 0.765 to 0.891, and 0.675 to 0.869, respectively DN and IN Drinking Behaviors and Reasons for Abstaining from Drinking factors, which met the criteria of a good internal consistency (Terwee et al., 2007). Hence, it can be assumed the questionnaire is internally consistent.

In relation to convergent validity analysis, smoking was associated with enhancement dinking motives for all reference groups. Students who have smoking habits, are more likely to present alcohol consumption (Deressa & Azazh, 2011; Harrison et al., 2009; Peltzer & Pengpid, 2014), possibly due to peer-effect and higher levels on social norms (Phua, 2011). Additionally, age and gender were associated with drinking motives in our sample, where for age (Cooper, 1994; Peltzer & Pengpid, 2014; Primack et al., 2012; Saddleson et al., 2015) and gender (Cooper, 1994; King & Chassin, 2007; Kraemer et al., 2015) similar results were found.

Concerning descriptive norms, DB and RAD for Typical students were associated with social drinking motives and RAD with enhancement motives. Also, regarding Acquaintances, RAD was associated with social motives. For Good friends, DB was associated with enhancement and coping motives. These associations between DB and RAD, across the different reference groups, could be related to an interaction between descriptive norms with social identity (Rinker & Neighbors, 2014) and students’ protective behavioral strategies (Arterberry, Smith, Martens, Cadigan, & Murphy, 2014; Dvorak, Pearson, Neighbors, & Martens, 2015).

Alcohol consumption is influenced by a variety of cultural norms, which are defined by beliefs, attitudes and behaviors (Grønkjær, Curtis, De Crespigny, & Delmar, 2011). Also, the individual’s perception of their social environment, as well as the cultural norms, the influence of students’ peers (Fitzpatrick, Martinez, Polidan, & Angelis, 2015; Merrill, Carey, Reid, & Carey, 2014; Pedersen, LaBrie, & Lac, 2008), their need for social approval (Rimal & Mollen, 2013) and their consumption intention (Park, Klein, Smith, & Martell, 2009) may influence alcohol consumption. These effects could explain the association observed between DB (Acquaintances and Good friends) with enhancement, coping, conformity and social drinking motives.

Geographical restrictions (the student sample were all from the same university) might represent a study limitation, which could influence consumption behaviors assessment. Concerning construct validity, it was only possible to assess the convergent aspect and not the discriminant and predictive validity.

Also, other factors could have made it more difficult for the students’ to answer the questionnaire, such as the students having to answer the same item for three different reference groups, which may have led to respondent fatigue, a common occurrence among respondents of surveys, especially complicated and/or lengthy surveys. Additionally, the possibility of the lack of a well-established definition, at that point of the time, of their social network (what is and who can be considered a typical college student, an acquaintance and a good friend) may have caused some confusion in their comprehension of such terms.

Nevertheless, our results concur with the findings in other studies concerning the relationship between drinking behaviors with both descriptive and injunctive norms (Arterberry et al., 2014; Fitzpatrick et al., 2015; Rimal & Real, 2005).

Future studies should focus on confirmatory analysis, leading to a better construct validation, exploring discriminant, convergent and divergent analysis.

Conclusion

This study undertook to translate and cultural adapt the Descriptive and Injunctive Norms Drinking and Abstaining Behaviors Questionnaire to Portuguese. The measure showed good psychometric properties considering its factorial validity, internal consistency and convergent validity using a sample of university students. Thus, this questionnaire may be useful to assess drinking behaviors concerning injunctive and descriptive norms of university students. The reliable assessment of these aspects could be advantageous to develop and manage health and psychoeducational interventions, demystifying students’ social norms and improving drinking behaviors.

References

- Arterberry, B. J., Smith, A. E., Martens, M. P., Cadigan, J. M., & Murphy, J. G. (2014). Protective behavioral strategies, social norms, and alcohol-related outcomes. Addiction Research & Theory, 22(4), 279–285. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2013.838226

- Borsari, B., & Carey, K. B. (2003). Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: a meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 64(3), 331–341. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social Research Methods (Fourth Edi). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Carey, K. B., Borsari, B., Carey, M. P., & Maisto, S. A. (2006). Patterns and importance of self-other differences in college drinking norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 20(4), 385–393. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-164X.20.4.385

- Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R., & Kallgren, C. A. (1990). A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(6), 1015–1026. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.6.1015

- Cooke, R., Sniehotta, F., & Schuz, B. (2006). Predicting binge-drinking behaviours using an extended TPB: examining the impact of anticipated regret and descriptive norms. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 42(2), 84–91. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agl115

- Cooper, M. L. (1994). Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment, 6(2), 117–128. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.117

- Deressa, W., & Azazh, A. (2011). Substance use and its predictors among undergraduate medical students of Addis Ababa University in Ethiopia. BMC Public Health, 11, 660. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-660

- DiStefano, C., & Morgan, G. B. (2014). A Comparison of Diagonal Weighted Least Squares Robust Estimation Techniques for Ordinal Data. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 21(3), 425–438. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.915373

- Dotson, K. B., Dunn, M. E., & Bowers, C. A. (2015). Stand-Alone Personalized Normative Feedback for College Student Drinkers: A Meta-Analytic Review, 2004 to 2014. PLOS ONE, 10(10), e0139518. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0139518

- Dvorak, R. D., Pearson, M. R., Neighbors, C., & Martens, M. P. (2015). Fitting in and standing out: Increasing the use of alcohol protective behavioral strategies with a deviance regulation intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(3), 482–493. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038902

- Eisenberg, D., Golberstein, E., & Whitlock, J. L. (2014). Peer effects on risky behaviors: new evidence from college roommate assignments. Journal of Health Economics, 33(1), 126–138. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.11.006

- El Ansari, W., Vallentin-Holbech, L., & Stock, C. (2014). Predictors of illicit drug/s use among university students in Northern Ireland, Wales and England. Global Journal of Health Science, 7(4), 18–29. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v7n4p18

- Fernandes-Jesus, M., Beccaria, F., Demant, J., Fleig, L., Menezes, I., Scholz, U., … Cooke, R. (2016). Validation of the Drinking Motives Questionnaire - Revised in six European countries. Addictive Behaviors, 62, 91–98. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.06.010

- Fitzpatrick, B., Martinez, J., Polidan, E., & Angelis, E. (2015). The Big Impact of Small Groups on College Drinking. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 18(3). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.18564/jasss.2760

- Gasparotto, G. D. S., Fantineli, E. R., & Campos, W. De. (2015). Tobacco use and alcohol consumption associated with sociodemographic factors among college students. Acta Scientiarum. Health Sciences, 37(1), 11. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.4025/actascihealthsci.v37i1.24109

- Gebreslassie, M., Feleke, A., & Melese, T. (2013). Psychoactive substances use and associated factors among Axum University students, Axum Town, North Ethiopia. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 693. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-693

- Grønkjær, M., Curtis, T., De Crespigny, C., & Delmar, C. (2011). Acceptance and expectance: Cultural norms for alcohol use in Denmark. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 6(4), 8461. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v6i4.8461

- Hagger, M. S., Wong, G. G., & Davey, S. R. (2015). A theory-based behavior-change intervention to reduce alcohol consumption in undergraduate students: Trial protocol. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 306. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1648-y

- Harrison, E. L. R., Hinson, R. E., & McKee, S. A. (2009). Experimenting and daily smokers: Episodic patterns of alcohol and cigarette use. Addictive Behaviors, 34(5), 484–486. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.12.013

- Hoffman, L., Paris, S., & Man, E. (1994). Development Psychology Today. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- John, B., & Alwyn, T. (2014). Revisiting the rationale for social normative interventions in student drinking in a UK population. Addictive Behaviors, 39(12), 1823–1826. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.07.022

- King, K. M., & Chassin, L. (2007). A prospective study of the effects of age of initiation of alcohol and drug use on young adult substance dependence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68(2), 256–265.

- Kraemer, K. M., McLeish, A. C., & O’Bryan, E. M. (2015). The role of intolerance of uncertainty in terms of alcohol use motives among college students. Addictive Behaviors, 42, 162–166. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.11.033

- Krieger, H., Neighbors, C., Lewis, M. A., LaBrie, J. W., Foster, D. W., & Larimer, M. E. (2016). Injunctive Norms and Alcohol Consumption: A Revised Conceptualization. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 40(5), 1083–1092. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.13037

- McGloin, J. M., Sullivan, C. J., & Thomas, K. J. (2014). Peer Influence and Context: The Interdependence of Friendship Groups, Schoolmates and Network Density in Predicting Substance Use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(9), 1436–1452. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0126-7

- Meisel, S. N., Colder, C. R., & Read, J. P. (2016). Addressing Inconsistencies in the Social Norms Drinking Literature: Development of the Injunctive Norms Drinking and Abstaining Behaviors Questionnaire. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 40(10), 2218–2228. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.13202

- Merrill, J. E., Carey, K. B., Reid, A. E., & Carey, M. P. (2014). Drinking reductions following alcohol-related sanctions are associated with social norms among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 28(2), 553–558. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034743

- Neighbors, C., O’Connor, R. M., Lewis, M. A., Chawla, N., Lee, C. M., & Fossos, N. (2008). The relative impact of injunctive norms on college student drinking: The role of reference group. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 22(4), 576–581. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013043

- O’Malley, P. M., & Johnston, L. D. (2002). Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement, (s14), 23–39. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23

- Park, H. S., Klein, K. A., Smith, S., & Martell, D. (2009). Separating Subjective Norms, University Descriptive and Injunctive Norms, and U.S. Descriptive and Injunctive Norms for Drinking Behavior Intentions. Health Communication, 24(8), 746–751. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/10410230903265912

- Pedersen, E. R., LaBrie, J. W., & Lac, A. (2008). Assessment of perceived and actual alcohol norms in varying contexts: Exploring Social Impact Theory among college students. Addictive Behaviors, 33(4), 552–564. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.11.003

- Peltzer, K., & Pengpid, S. (2014). Tobacco Use, Beliefs and Risk Awareness in University Students from 24 Low, Middle and Emerging Economy Countries. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 15(22), 10033–10038. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.22.10033

- Perkins, H. W. (2002). Social norms and the prevention of alcohol misuse in collegiate contexts. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement, (s14), 164–172. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.164

- Phua, J. (2011). The influence of peer norms and popularity on smoking and drinking behavior among college fraternity members: A social network analysis. Social Influence, 6(3), 153–168. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/15534510.2011.584445

- Primack, B. A., Kim, K. H., Shensa, A., Sidani, J. E., Barnett, T. E., & Switzer, G. E. (2012). Tobacco, marijuana, and alcohol use in university students: a cluster analysis. Journal of American College Health : J of ACH, 60(5), 374–386. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2012.663840

- Reed, M. B., McCabe, C., Lange, J. E., Clapp, J. D., & Shillington, A. M. (2010). The Relationship between Alcohol Consumption and Past-Year Smoking Initiation in a Sample of Undergraduates. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 36(4), 202–207. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2010.493591

- Reid, A. E., & Carey, K. B. (2015). Interventions to reduce college student drinking: State of the evidence for mechanisms of behavior change. Clinical Psychology Review, 40, 213–224. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.06.006

- Rimal, R. N. (2008). Modeling the Relationship Between Descriptive Norms and Behaviors: A Test and Extension of the Theory of Normative Social Behavior (TNSB). Health Communication, 23(2), 103–116. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/10410230801967791

- Rimal, R. N., & Mollen, S. (2013). The role of issue familiarity and social norms: findings on new college students’ alcohol use intentions. Journal of Public Health Research, 2(1), 7. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.4081/jphr.2013.e7

- Rimal, R. N., & Real, K. (2005). How Behaviors are Influenced by Perceived Norms. Communication Research, 32(3), 389–414. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650205275385

- Rinker, D. V., & Neighbors, C. (2014). Do different types of social identity moderate the association between perceived descriptive norms and drinking among college students? Addictive Behaviors, 39(9), 1297–1303. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.03.018

- Saddleson, M. L., Kozlowski, L. T., Giovino, G. A., Hawk, L. W., Murphy, J. M., MacLean, M. G., … Mahoney, M. C. (2015). Risky behaviors, e-cigarette use and susceptibility of use among college students. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 149, 25–30. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.01.001

- Schreiber, J. B., Nora, A., Stage, F. K., Barlow, E. A., & King, J. (2006). Reporting Structural Equation Modeling and Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results: A Review. The Journal of Educational Research, 99(6), 323–338. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338

- Schuckit, M. A., Smith, T. L., Clausen, P., Skidmore, J., Shafir, A., & Kalmijn, J. (2016). Drinking Patterns Across Spring, Summer, and Fall in 462 University Students. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 40(4), 889–896. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.13019

- Scott-Sheldon, L. A. J., Carey, K. B., Elliott, J. C., Garey, L., & Carey, M. P. (2014). Efficacy of alcohol interventions for first-year college students: A meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(2), 177–188. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035192

- SICAD. (2015). Relatório Anual 2014: A Situação do País em Matéria de Álcool. Retrieved from http://www.sicad.pt/BK/Publicacoes/Lists/SICAD_PUBLICACOES/Attachments/79/Relatório Anual 2014 - A Situação do País em Matéria de Álcool.pdf

- Silva, D. A. S., & Petroski, E. L. (2012). The simultaneous presence of health risk behaviors in freshman college students in Brazil. Journal of Community Health, 37(3), 591–598. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-011-9489-9

- Terwee, C. B., Bot, S. D. M., de Boer, M. R., van der Windt, D. A. W. M., Knol, D. L., Dekker, J., … de Vet, H. C. W. (2007). Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 60(1), 34–42. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012

- World Health Organization. (2017). Process of translation and adaptation of instruments. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

19 November 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-047-1

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

48

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-286

Subjects

Health, psychology, health psychology, health systems, health services, social issues, teenager, children's health, teenager health

Cite this article as:

Ramalho Mostardinha, A., Bártolo, A., & Pereira, A. (2018). A Study On The Validation Of The Drinking And Abstaining Behaviors Questionnaire Among Portuguese University Students. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, R. X. Thambusamy, & C. Albuquerque (Eds.), Health and Health Psychology - icH&Hpsy 2018, vol 48. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1-16). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.11.1