Abstract

Reforms in education, both in Israel and worldwide, are always implemented in “top-down.” The teachers are not partners in the planning and implementation of the reforms, and usually there is no correlation between the top-down policy that is scheduled for implementation in the field, and the relevant needs of teachers. Therefore, teachers often accept upon themselves to implement a policy that they do not share, or even contradicts their needs and opinion. The situation created does not allow for growth and development of the professional identity of educators, and sometimes undermines it. Educational reforms that are planned and implemented as a top-down directive, do not contribute to the formation of teachers’ professional identity. Today, educators stand “between a rock and a hard place,” between the necessity to teach and to show results, and the necessity of implementing a reform that reflects one or another current political need of the Ministry of Education, and does not necessarily correctly answer to educators, who are committed to show results. The aim of this article is to point out the negative connection between the phenomenon of educational reforms imposed in top-down, and the development of teachers’ professional identity, to demonstrate how this occurs, and to propose a conceptual framework for additional possibilities that will provide a way to involve educators in creating a reform in the education system, that will answer the relevant needs from the field, and will allow development of the professional identity of teachers who are supposed to implement the reform.

Keywords: Teachers’ professional identityeducational reformsprocesses of educational changetop-down changebottom-up change

Introduction

This article deals with the link between the manner in which reforms in education are led, and teachers’ professional identity. The fundamental assumption in this article is that teachers’ professional identity is critical, because the teacher is the one who stands before the students and represents the policy. The teacher mediates between the various reforms to the field, the teaching, and the daily contact with the student. The research literature points to the fact that the reforms usually take place “from top down,” and thus seriously impair the perception of the teacher’s professional identity. Therefore, this article will aim to propose a conceptual framework and a new theoretical model that will enable the teacher to be a full partner in the creation and implementation of the reform.

What is Identity?

The term “identity” can be defined by the question “who is or what is the person?” The different answers that a person gives themselves, or the meanings attributed to them by others, are those that define their identity (Beijaard, 1995). The early literature, such as Erikson (1968), describes the concept of identity in terms of the ‘self.’ According to Erikson, identity is a concept that changes and develops with age, which does not relate to what a person has, but to what they develop during their lifetime.

The research views identity creation as an ongoing process, that includes repeated interpretation of experiences encountered by the individual (Kerby, 1991). Identity formation involves the process of creating identity, expanding it, and making changes within it through actions of self-evaluation (Cooper & Olson, 1996). Self-evaluation and identity are part of a person’s self-image and may therefore be threatened by changes that may affect their self-image and, consequently, their personal identity (Kozminsky & Kluer, 2011).

Part of a person’s self-identity is also their professional identity, which answers the question “Who or what am I as a professional?”

Professional identity is defined as the teachers’ sense of belonging to the teaching profession and their identification with it (Tickle, 1999; Kremer & Hoffman, 1981). Coldron and Smith (1999) expand this definition and explain that professional identity is the way the teacher is perceived not only to themselves but also by others. As a result, “self-perception” and “perception of others” are two elements whose interactions affect the professional identity and are affected by it (Reynolds, 1996).

Beijaard, Verloop, and Vermunt (2000) examined the factors affecting the construction of the professional identity of veteran teachers. The study conclusions are that throughout the years of teaching there is a change in the self-perception of professional identity. The change occurs because there is an ongoing dynamic development process in an attempt to create a coherent professional identity (Kozminsky & Kluer, 2011).

There is a mutual influence between the professional identity and self-identity, each identity affects and is affected by the other, and therefore a change in any of them generates an impact (Kozminsky & Kluer, 2011).

Beijaard, Verloop, and Vermunt (2000) note that the professional identity of teachers influences their sense of self-efficacy, and their willingness to cope with educational changes.

Coldron and Smith (1999) describe the professional identity of teachers as a personal and social biography. In their opinion, part of this identity is at the choice of the teachers, while part of it is imposed upon them by society. Thus, the researchers accept the opinion of Louden (1991), and Goodson (1992), who claim that the identity of teachers consists of personal and social biographies, both of these biographies influence their experiences and their personal identity as teachers.

In the postmodern era, characterized by constant economic, social and cultural changes, and with a great deal of diverse and partly contradicting information, it is difficult to formulate a professional identity. Reforms and changes in the education system may create conflicts and crises among teachers, that have negative implications for their development of professional identity, on the commitment to teaching, motivation, professional pride, and their sense of internal cohesion (Day, Elliot, & Kington, 2005; Kozminsky, 2011). The conflicts about professional identity are derived from the human-context interaction (Berzonsky, 2008; Bosma & Kunnen, 2001; Kerpelman, Pittman, & Lamke, 1997). Raising these conflicts to the surface may contribute to teachers’ professional efficiency, their work satisfaction, and professional longevity (Chong, Low & Goh, 2011; Kremer & Hoffman, 1981).

Conflicts within the professional identity may undermine teachers’ sense of coherence of their self-identity (Day, Elliott & Kington, 2005). They also argue that a change in educational policy and reforms, that usually occur as an expression of policy from above rather than a need from the field, create an ongoing identity crisis. They found that the crisis damages their commitment to teaching, the degree of motivation, sense of self-efficacy, satisfaction and professional pride, and their own internal coherence in relation to their professional identity. Hence the importance of this article.

Reforms in Israel’s Education System

Vidislavski (2011) defines a reform as “A fundamental reform, changing values; changing order, correcting, changing shape or value.”

The Longman dictionary defines reform as “a change or changes made to a system or organization in order to improve it”

Wideen and Grimmett (1995) define educational reform as a planned process of change aimed at achieving desirable objectives from the point of view of its initiators.

Educational reforms play a crucial role in shaping the education system and adapting it to the emerging reality in their implementation (Schechter, 2015). Reforms in education are designed to facilitate “Fundamental and comprehensive changes in the education system and in schools. They deal with fundamental questions of education: redefine the educational process and its goals, determine the main points of its content, and propose ways to realize them.” (Shmida, 1997). Education Reforms should strive for innovation, progress and flexibility, while understanding the future needs of the students (Schechter, 2015), and therefore when conducting a reform, it is important to examine what it brings, does it come to provide an appropriate response and to prepare students for the skills of the 21st century? (Schechter, 2015). At the same time, we must remember, that teachers are the ones who carry out the reform in practice, and therefore we must also ask whether the teachers are prepared and capable of implementing the reform? Have the conditions been adapted in order for them to perform what is expected from them? Have the teachers undergone preparation and professional training for the developing reform plan, and are the physical and technological conditions adapted to the new demands?

The research of my doctoral dissertation that is currently being written deals with the examination of teachers’ professional identity, who are supposed mediate and implement the ‘Ofek Hadash’ reform in the field. The study examines the issue of professional identity through the professional development processes that were presented as one of the goals of the ‘Ofek Hadash’ reform. This article seeks to examine the professional identity of the teachers, who are required to mediate and implement a reform that in most cases were not part of its planning, and in most cases does not meet their real needs in the field, and proposes a theoretical model for planning reforms and changes in the education system while designing a central place for the teachers who mediate these changes to the students.

Over the past decade, the Israeli education system underwent several major reforms: ‘Ofek Hadash’ (2008), ‘Oz LeTmura’ (2011) and ‘Israel Ola Kita’ (2014). The first relates to elementary and junior high schools, the second to secondary schools, and the third relates to changing the structure of the matriculation certificate (“Meaningful Learning”). In this article, I will refer to reforms in the education system as a process of change.

The ‘Ofek Hadash’ reform: The four main objectives that have been set are: (Schechter, 2015)

1.Implementing education-teaching-learning processes focused on the individual.

2.Constructing the teacher’s work – organizing the pedagogic and academic work in frontal teaching hours, individual teaching hours and hours of stay.

3.Empowering teaching and management staff through professional development throughout their careers; Improving the status of teachers and raising their salaries.

4.Strengthening teaching and management through assessment processes of teaching staff; empowering and expanding the authority of the school principal.

The ‘Oz-LeTmura’ reform: Its main objective is to advance the achievements of the education system, and to strengthen the status of the teacher in the upper echelons. The reform is aimed at improving the effectiveness of the school by improving scholastic achievements, promoting a meaningful school discourse and developing an optimal educational climate.

The ‘Israel Ola Kita’ reform: “The education system strives to develop through processes of meaningful learning and a flexible learning structure – adapted to socio-cultural, economic and technological change processes – an independent learner who is aware of their learning processes and is able to define personal and social objectives and to implement them, who had a capability to learn in different environments, and is able to have reciprocal relations with people based on humanistic values.”

Leading Change in the Education System

There is general agreement both in the research literature and in society that the school must change to meet the changing societal needs (Gorodetsky & Weiss, 2010). “We do not have the choice between wanting or not wanting changes in education, we must make changes in the education system in order to continue to survive as a society.” (Fullan, 1993).

A change in the field of education is generally perceived as an educational reform designed to achieve desirable objectives – desirable at least to the proponents of change (Wideen & Grimmett, 1995, p. 4).

The process of change occurs in three areas: cognitive, emotional and behavioral (Fuchs, 1995, pp. 29-30). This process is a complex process that combines cognitive, effective and practical aspects.

Stage One: Preparing for change – making a decision to change, learning, planning and organizing towards the implementation of the change. This stage mostly addresses the cognitive and emotional aspects.

Stage Two: Making the change (the behavioral aspect).

Stage Three: Evaluation of the results according to pre-determined operational criteria. (Fuchs & Hertz Lazarowitz, 1992: 13; Porat, 1998).

The change processes reported in the research literature relate to the source of authority and knowledge that drive the change (Porat, 1998). In the traditional top-down strategy, the source of authority for applying the change is a factor outside of the school, the “expert”, that brings with it the knowledge, marks the goals, ranks them, and guides the teachers on the way to achieving them. In the bottom-up developmental strategy, the source of authority and power, both with regard to knowledge, and with regard to the desired change processes, lies within the school, with the teachers and the management. In this strategy, the teachers’ practical knowledge is perceived as the significant knowledge that is supposed to nourish the processes of change. Therefore, the starting point for change is found in school activity, when the interactions between teachers, while clarifying the knowledge they bring to the initiative of change, offer possible implications for change, and are the driving force for the possible growth of new activity (ibid).

To date, no clear preferable strategy has been found to leading and implementing change in the education system. And yet it is clear that the top-down change is easier to implement. An external factor declares what the change is, comes with the rationales and the knowledge, and the teachers “only” need to implement it, i.e. to replace what they have done so far with something else (ibid). This traditional top-down strategy for leading change turns out to be rather poor, even if it is simpler to implement. Studies that addressed this deficiency suggest possible causes that prevent the process of change from coming about. Angus (1998) believes that the requirement to replace the existent in the change process motivates the teachers to use “counter-force” and produces a “network of forces” that covertly opposes to change. Sarason (1971) argues that the replacement of the teacher’s pattern of action into an action pattern which is imported from an external source, fosters authority rather than openness among the different components in the school, and counteracts the curiosity and motivation that are in the basis of a meaningful change. McLaughlin (1994) focuses the problem in the transmission of messages between the headquarters, the external factor, and the field. She claims that the message inherent in change when planning the move outside the school dissolves in the transition to the field, and that is why she emphasizes the importance of the “intermediary of change”, i.e. the faculty at all levels of the school. In other words, the level of dedication and commitment of the school to applying the changes is a very significant factor in determining the nature of the change that will actually occur.

The problem before us, therefore, is what is the model of the desired change, when the top-down change is ineffective, whereas the next change from the field, called the “developmental strategy”, is too slow. At the level of school conduct, ongoing legitimacy is required, not only to raise questions regarding the existing activity, but also with respect to the new activity that is taking shape. In addition, a large number of teachers is needed, who are committed to the other work that may be required of the cooperative learning. Funders generally do not tend to fund such processes for a variety of reasons, partly because of the fear of the sluggishness of the change processes that grow from the school, due to lack of confidence in teachers’ ability to lead such moves, or because such processes may encourage the school’s release from external dictates (Gorodetsky & Weiss, 2010).

There are those who believe that a successful process of change will occur when it is activated simultaneously by internal and external forces (Yosifon, 1997; Schlechty, 1990, Hargreaves, 1994, Fullan & Steigelbauer, 1991).

Gorodetsky and Weiss, (2010) examined the case of the pilot attempt that took place in Israel in the mid-1990s: “The Thirty Towns Project”. In this project, autonomy was granted to 30 communities to reconstruct the concept of education at the locality level in the holistic approach. The project was launched in Be’er Sheva, a large city in southern Israel, and was called “Eshkolot Chinuchiim” (educational clusters) (Gorodetsky, 1996). The article deals with the analysis of insights that emerged in the collaborative learning processes that took place during the first year of the project’s activity. The analysis of insights in the study referred to two dimensions involved in the processes of change (McWhinney, 1997).

One dimension relates to the options of change, that is, to the availability of ideas, symbols, principles or values that open creative and novel possibilities of action that deviate from the routines that already exist in the school. The other dimension relates to the degree of involvement of the factor that should be active in implementing the changes - the agency. This dimension expresses the degree of initiative, authority, responsibility and commitment of members of the community to the process of change. The main insights that the authors of the article bring are: in all the schools that were part of the educational cluster there was actual action. Not all of them were successful, but there was meaningful activity. This process was stopped before its completion due to “the constraining power of the centrality in the educational system.” (Gorodetsky & Weiss, 2010). The Ministry of Education and the local authority have parachuted a new project called “Madarom” (raising students’ achievements in the south of Israel, mainly in science and technology). There were attempts to combine the many activities in the educational clusters with the new project, but these attempts were unsuccessful because of the rigid framework imposed by the program.

This experience teaches us that when we allow the field to think and act, the results are much better than if the change is imposed from above. The covert and overt struggle between the authority powers and the field creates conflicts and prevents actual assimilation of a change from the field that expresses the desire of the teachers.

Schechter, in his book, “Let us lead! School principals at the forefront of reforms”, refers to school principals responsible for the implementation of educational reforms (his book refers to the two recent reforms: “New Horizon” and “Oz LeTmura”). In the book’s epilogue, Schechter proposes a fundamental change in the way of creating educational reforms. His proposal includes first of all attention to the field itself, which brings with it a great deal of experience and knowledge, while simultaneously requiring the headquarters to allow this process to happen and to help adapt it to the entire system. Schechter points to the cooperative discourse among all stakeholders as a basic component.

Problem Statement

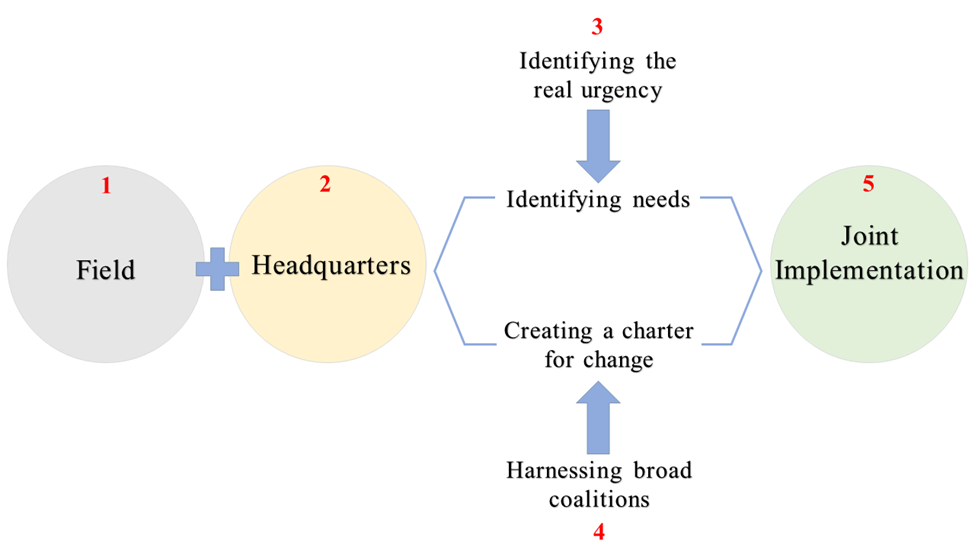

Based on the literature reviewed and the professional experience of the writer, this article seeks to propose a new conceptual framework: (a combination of Schechter, Kotter and my unique addition)

Basic Assumptions:

1.The teacher’s professional identity is significant because the teacher, who teaches in the classroom and is constantly interacting with the students, does so as part of their personality, which includes their professional identity. Teachers are people who bring themselves and their personal identity to the classroom; (Kozminsky, 2008).

2.Professional identity is based on a sense of belonging, self-efficacy, and a sense of autonomy (Beijaard, Verloop, & Vermunt, 2000; Kremer & Hoffman, 1981).

3.A change in the education system is necessary in order to avoid stagnation, and to adapt it to changing times and the progress of technology, research and global processes. At the same time, frequent changes that do not allow the previous change to be assimilated, does not allow a real, in-depth change, and creates constant objections among teachers. Gorodetsky & Weiss, 2010).

4.A top-down change raises objections, whereas a bottom-up change increases the chances of harnessing and enriching educational activity, and even gives appropriate expression to the true needs of the teachers (Porat, 1998).

Findings

Explanation of the model:

The “field” (1): Schools have principals and teachers, parents and students. On the surface it seems complicated to slow implementation, and there is no chance of reaching an agreement. It is recommended to work in the method used in the model of the “The Thirty Towns Project” in Israel, while taking into account findings from the research conducted to evaluate the project (Nevo & Friedman, 2000).

The “headquarters” (2): The Ministry of Education, which includes the political and professional echelons, local authorities, education departments, and foundations interested in donating money to a specific project regardless of what is happening in the field.

“Identifying the real urgency” and the needs “in the field” (3): in his first book, “Leading Change” (1996), Kotter investigated about 100 organizations that invested great effort in leading change. His first book suggests eight necessary stages for leading a successful change. His current book, “A sense of urgency” (2008), while based on the previous study, stresses that the “urgency” stage is the most important and critical, emphasizing that the “real urgency” (as opposed to “imagined urgency”) must be identified. Kotter claims that without a real sense of urgency among all the members of the organization, any attempt to lead change is doomed to failure. The real urgency is of paramount importance because it transforms the one-time change into an ongoing process built into the organizational culture. The meaning of “real urgency” is “pressing importance”, i.e., critically important. These are key challenges to success or survival, to victory or failure. This stage in the proposed model is supposed to identify the “real urgency” of the needs of the field, first and foremost of the teachers - who will be the agents and intermediaries of change.

“Harnessing broad coalitions and creating a charter for change” (4): or “team collaboration strategy” (Kotter, 2006, in Schechter). Kotter argues that “No single individual, not even a king-like CEO, can ever formulate the right vision, distribute it ... There is always a need for a coalition...” There is a need to involve very broad coalitions in the field, in each of the schools on all levels of the organization: the principal, teachers, students, parents and administrative staff. The broader the coalition, the easier it will be to cope with objections, that in this situation, may be very limited and can be dealt with.

“Joint Implementation” (5): the meaning of joint implementation is shared for the field and the headquarters. Without massive support from the headquarters, it will not be possible to implement change and reform in the educational system. There is a need for budgets and the establishment of priorities in the system.

Conclusion

How Will the Proposed Model Improve and Develop the Teacher’s Professional Identity?

When teachers perceive the reform as forced upon them, their morale, commitment and professional growth are damaged, and a sense of bitterness is created towards their superiors. Studies have found that forced change has caused many teachers to have skepticism and passivity and their ability to set goals and develop skills was impaired (Optalka, 2010).

The novelty of the proposed model is in the full cooperation of teachers in creating and implementing the reform in the education system, as can be seen from the literature review, the change imposed from top-down, raises many objections. The collaboration will enable teachers to develop themselves and grow with the change, while giving authentic expression to the needs of the field as expressed in the teacher’s daily work. The collaboration will give the teacher a sense of belonging, self-efficacy, and thus raise and validate his sense of professional identity.

Reforms in the education system are necessary in order to adapt to progress and the changing reality. Given that the actual implementers of change are the teachers, they should be considered as senior partners in conceptualizing, creating, and implementing the change. The partnership will enhance teachers’ sense of belonging, and provide a suitable response to their needs. These, no doubt, will enhance and improve the sense of professional identity of the teacher – at school, in the classroom in front of their students, and in their role in the educational community. At the same time, in order for such a change to take place, there is a need for a presence that will influence and support the headquarters – the education system, the Ministry of Education that ultimately determines policy. Without a broad wall-to-wall coalition of the Ministry of Education, even if the teachers are full partners in the change, a reform will not be able to commence.

References

- Angus, M. (1998). The rules of school reform. London: The Falmer Press.

- Beijaard, D. (1995). Teachers' prior experiences and actual perceptions of professional identity. Teachers and Teaching, 1(2), 281-294.

- Beijaard, D., Verloop, N., & Vermunt, J. D. (2000). Teachers’ perceptions of professional identity: An exploratory study from a personal knowledge perspective. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16(7), 749-764.

- Berzonsky, M. D. (2008). Identity formation: The role of identity processing style and cognitive processes. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(3), 645-655.

- Bosma, H. A., & Kunnen, E. S. (2001). Determinants and mechanisms in ego identity development: A review and synthesis. Developmental Review, 21(1), 39-66.

- Chong, S., Low, E. L., & Goh, K. C. (2011). Emerging Professional Teacher Identity of Pre-Service Teachers. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 36(8), 50-64.

- Coldron, J., & Smith, R. (1999). Active location in teachers' construction of their professional identities. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 31(6), 711-726.

- Day, C., Elliot, B. & Kington, A. (2005). Reform, standards and teacher identity: Challenges of sustaining commitment. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21(5), 563-567.

- Erikson, E.H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

- Fuchs, I. (1995). Change: A way of life in schools. Tel-Aviv: Cherikover publishers. (In Hebrew).

- Fuchs, I. & Hertz Lazarowitz, R. (1992). The principal’s role as a policy planner. Haifa University and the Ministry of Education. (In Hebrew).

- Fullan, M. (1993). Change forces: Probing the depths of educational reform (Vol. 10). Psychology Press.

- Fullan, M. & Steigelbauer, S. (1991). The new meaning of educational change. New York: Teaching College Press.

- Goodson, I. (1992). Studying teachers' lives. London: Routledge.

- Gorodetsky, M. (1996). Educational clusters. In Welber, Y. & Nagar, G. (Eds.), Atid, 19-34. Beer Sheva: Ministry of Education, Southern District. (In Hebrew).

- Gorodetsky, M., & Weiss, T. (2010). Conditions for educational change processes in educational settings: Multiplicity of educational alternatives and responsible agency. Dapim, 50, 48-74. http://www.mofet.macam.ac.il/eng/writing/Documents/dapim50eng.pdf

- Hargreaves, A. (1994). Changing teachers, changing times: Teachers' work and culture in the postmodern age. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Kerby, A. P. (1991). Narrative and the Self. Indiana University Press.

- Kerpelman, J. L., Pittman, J. F., & Lamke, L. K. (1997). Toward a microprocess perspective on adolescent identity development: An identity control theory approach. Journal of Adolescent Research, 12(3), 325-346.

- Kotter, J. P. (1996). Leading change. Harvard Business Press.

- Kotter, J. P. (2008). A sense of urgency. Boston: Harvard Business Press.

- Kozminsky, L. (2001). Professional identity of teachers and teacher educators in a changing reality.

- Kozminsky, L. (2008). Professional identity in teaching. Shviley Mechkar, 15, 13-17.

- Kozminsky, L. (2011). Professional identity of teachers and teacher educators in a changing reality. In Teachers’ life-cycle from initial teacher education to experienced professional. Proceedings of the ATEE 36th Annual Conference, 12-19.

- Kozminsky, L., & Kluer, R. (2011). The construction of the professional identity of teachers and teacher educators in a changing reality. Dapim, 49. Mofet Institute. (in Hebrew).

- Kremer, L., & Hoffman, Y. (1981), Professional identity and leaving the teaching profession, Iyunim beHinuch, 30, 99-108. (In Hebrew).

- Louden, W. (1991). Understanding teaching: Continuity and change in teachers' knowledge. New York: Cassel.

- McLaughlin, M. W. (1994). Strategic sites for teachers’ professional development. In Grimette, P. P., & Neufeld, J. (Eds.), Teacher development and the struggle for authenticity: Professional growth and restructuring in the context of change, 31-35. New York: Teacher College Press.

- McWhinney, W. (1997). Paths of change: Strategic choices for organizations and society. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Nevo, D., & Friedman, E. (2000). External evaluation of the “Thirty Towns Project” (the holistic project) for the years 1996-1998. Tel Aviv University, School of Education.

- Optalka, I. (2010). Teachers and principals in ‘Ofek Hadash’: From opposition to participation. Hed Hachinuch, 3, 28-30. (In Hebrew).

- Porat, N. (1998). Under the "umbrella of change" in the education system. Halacha Vemaase Betichnun Limudim, 3, 38- 59. (In Hebrew).

- Reynolds, C. (1996). Cultural scripts for teachers: Identities and their relation to workplace landscapes. In Kompf, M., Bond, W. R., Dworet, D., & Boak, R. T. (Eds.), Changing research and practice: Teachers’ professionalism, identities and knowledge. 69-77. London: Falmer Press.

- Schechter, C. (2015). Let us lead! School principals at the forefront of reforms. Ramot: Tel Aviv University Press.

- Sarason, S. (1971). The culture of school and the problem of change. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Schlechty, P. C. (1990). Schools for the twenty-first century: leadership imperatives for educational reform. The Jossey-Bass Education Series. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Inc., Publishers.

- Shmida, M. (1997). Reform in Education. In Kashti, I., Arieli M., & Shlasky, S. (Eds.), Teaching and Education Lexicon. Tel Aviv: Ramot, Tel Aviv University. (In Hebrew).

- Tickle, L. (1999). Teacher self-appraisal and appraisal of self. In Lipka, R. P., & Brinthaupt, T. M. (Eds.), The role of self in teacher development, 121–141. Albany, New York: SUNY Press.

- Vidislavski, M. (2011). Reforms in the Education System. Jerusalem: Ministry of Education. (In Hebrew).

- Wideen, M. F., & Grimmett, P. P. (1995). Changing times in teacher education: Restructuring or reconceptualization? London, UK: Falmer Press.

- Yosifon, M. (1997). Redesigning teaching patterns: researching the change process in one junior high school in Israel. PhD thesis in philosophy, under the supervision of Prof. Y. Kashti, Tel Aviv University, School of Education. http://cms.education.gov.il/EducationCMS/Units/HighSchool/IsraelOlaKita/Israel.htmernational

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

28 June 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-040-2

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

41

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-889

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Zeevi, A. (2018). Teachers’ Professional Identity In Light Of Reforms In Education. In V. Chis, & I. Albulescu (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2017, vol 41. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 735-744). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.06.88