Abstract

Problem Statement: Fear is the most significant consequence of direct or vicarious experience of violence and aggression in the workplace. Both entities significantly affect workers’ physical and psychological well-being. Research Question: How does workplace violence/aggression effect workers’ well-being? Purpose of the Study: To identify behaviours of psychological aggression perpetrated by the public which occur more often and to analyse the implications of workplace violence/aggression on individual psychological and physical well-being. Methods: Cross-sectional and correlational study, developed on a sample of 131 inspectors (68% women) with an average age of 41.89 years. Collection of data: Physical and Vicarious Violence at Work; Fear of Future Violent Events at Work; Workplace Aggression Questionnaire; General Health Questionnaire. Results: The prevalence of aggression in the workplace was significant (40% physical; 90% psychological; 76% vicarious and 50% fear). The results showed that the effects of aggression in the workplace on well-being are indirect effects and mediated by fear. Those who experience both physical and vicarious violence feel more fear and fear affects their physical and psychological well-being. Conclusion: The results convey information which supports conceptualization and assessment models of workplace aggression as a nosologic entity originating in negative physical and psychological experiences lived by individuals in their workplace. Knowledge and a better understanding of the types and dimensions of the phenomenon violence and aggression in the workplace is a powerful support instrument for defining more effective prevention strategies.

Keywords: Workplace, violence, aggression, fear, well-being

Introduction

The use of the term aggression at work to represent a broader construct where both terms, physical violence at work and psychological aggression at work are represented is common in the current occupational/organizational literature (Schat, Desmarais & Kelloway, 2006; Schat & Kelloway, 2005; e.g., Neuman & Baron, 1998).

Generally speaking, most researchers agree that aggression in the workplace is associated with the experience of a (1) potentially harmful behaviour (2) for which its target is motivated to avoid, and (3) which occurs while the target is at work (Schat & Frone, 2011; cf. definition proposed by Hershcovis and Barling, 2007). And within the super-construct of aggression in the workplace (Schat & Frone, 2011; e.g., Schat & Kelloway, 2005) the literature includes physical and psychological behaviours, which can be active or passive, explicit (overt) or not (covert), direct or indirect, against the organization (organizational aggression) or a person in the organization (interpersonal aggression) (Dionisi, Barling & Dupré, 2012, Hershcovis et al, 2007; eg., Arnold, Dupré, Hershcovis & Turner, 2011; Hershcovis, 2011).

Although the terms “aggression at work” and “violence at work” are often used interchangeably, they are different (Barling, Dupré & Kelloway, 2009). Schat and Kelloway (2005) suggest that physical violence at work is a distinct form of aggression in the workplace, comprising behaviours in order to physically assault the other (Barling, Dupré & Kelloway, 2009). All violent behaviours are aggressive but not all aggressive behaviours are violent (Barling, Dupré & Kelloway, 2009; e.g., Schat & Kelloway, 2005). Although similar empirically related, they correspond to different constructs (Barling et al. 1987 in Barling & Kelloway Dupré, 2009). Hitting, grabbing or spitting (or the threat thereof), more physical, i.e. behaviours that involve some form of physical contact (Dionisi, Barling & Dupré, 2012) concern physical violence at work; while being verbally insulted, being treated with disrespect, whose emphasis is more psychological in nature (Barling, Dupré & Kelloway, 2009; Shat & Frone, 2011), concern psychological aggression at work. Thus, within this more general construct that is aggression in the workplace (Schat & Kelloway, 2005; e.g., Schat & Frone, 2011), physical violence and psychological aggression are considered (Schat & Frone, 2011).

Based on the perpetrator-victim relationship, a four-type categorization of aggression in the workplace appears in the literature:when the perpetrator has no legitimate relationship with the targeted workers or the organization and usually came into the workplace to commit a crime, – occurs when the perpetrator has a legitimate relationship with the organization (e.g., customers, students, patients) and commits an aggressive act while being served, taught, cared for,aggression occurs when the perpetrator belongs to the organization (e.g., a current or former employee of the organization targeting another worker), – when the aggressor has a legitimate former or current relationship with the employee of the organization (friend or former spouse, acquaintance) (Barling, Dupré, & Kelloway, 2009 ; e.g., Dupré & Barling, 2003, LeBlanc & Barling, 2004).

The adverse effects of violence [and aggression] at work for individuals and organizations are numerous, varied and are related to the nature of violence [and aggression] (Barling, 1996; e.g., Dionisi, Barling & Dupré, 2012; Hershcovis & Barling, 2010a). Barling (1996) postulated that violence [and aggression] at work brings direct and indirect negative effects. The direct effects (e.g., fear, negative mood, cognitive distraction) are considered the first result of the psychological experience of violence [and aggression] at work. The indirect effects are the result of direct results, for example, indirect psychological (e.g., exhaustion, depression), psychosomatic (e.g., sleep problems, migraines, headaches) and organizational (e.g., absenteeism, accidents) results (Barling, 1996).

For Barling (1996), one of the consequences of exposure to violence [and aggression] at work, whether through direct or vicarious experience, is the fear of future violent events at work, because experiencing an act of violent and/or aggressive behaviour increases perceived vulnerability in individuals to experiencing such behaviour again (Barling, 1996; Schat, Desmarais & Kelloway, 2006). In addition, fear, negative emotional response (hostility, anxiety, irritation) in the worker in facing this event (Barling, 1996; Schat, Desmarais & Kelloway, 2006) will be something responsible for transmitting any effects of violence [and aggression] at work in psychological, psychosomatic and organizational results (Barling, 1996). Fear is thus an important construct, a central concept, in analysing the consequences of violence [and aggression] at work (Mueller & Tschan, 2011).

Problem statement

Aggression in the workplace exists and is associated with negative effects for individuals and organizations. It is predictable and can be prevented. It is considered an object of study by the scientific community and organizations (Baron & Neuman, 1996); (Barling, Neuman & Baron, 1996); (OIT; EU-OSHA, 2014). It is a major issue for everyone working but lacking statistical data. According to Eurofound (2015), Portugal joined the group of member states of the European Union where aggression issues at work are not a priority and by worker reporting rates are low, hence the interest in investigating it.

Aggression in the workplace is defined as “the behaviour of an individual or individuals, external or internal to the organization who intend to harm a worker or workers physically and psychologically, and that occurs in the workplace” (Schat & Kelloway, 2005, p.191). A definition which is i. broad, consistent with definitions used in the literature of human aggression in general ii. which includes a broad spectrum of physical (e.g., hitting) and nonphysical (e.g., being insulted verbally) behaviours, able to reflect a general construct of the phenomenon of aggression in the workplace iii. focused on behaviours that intend (here and now) to harm iv. inflicted by a variety of sources, belonging to the organization (e.g., supervisor, colleagues) or external to the organization (e.g., customers, patients), v. and that occurs in the context of work – time, place, functions related to work - (Barling, Dupré, & Kelloway, 2009; Schat & Kelloway, 2005). Thus, from the perspective of the worker who is the target of violent and aggressive behaviour at work (Hershcovis, 2011), we propose an approach that emphasizes individual perception of events in the workplace during the last 12 months, focused on the subjective experience of aggression at work. This was the focus of this study: the perspective of the public sector worker on the subjective experience of aggression; source of aggression, the public in a time period of 12months.

Research questions

How does the workplace violence/aggression effect workers’ well-being?

Purpose of the study

To assess the psychological experience of the work inspectors who are victims of violence and aggression perpetrated by customers/public is the main aim of this research. This study has the additional aim of identifying behaviours of psychological aggression perpetrated by the public which occur more frequently and to analyse the implications of workplace violence/aggression on individual psychological and physical well-being.

Research methods

Cross-sectional, analytic and correlational study, developed on an objective convenience sample of 131 inspectors, (32% men/68% women) with an average age of 41.89 years (±7.49), length of service of 6-19 years (40%), residing in Portugal.

The following were applied to collect data:

- Physical Violence at Work (Rogers & Kelloway, 1997); Workplace Aggression Questionnaire, (Schat, Desmairais & Kelloway, 2006); Vicarious Violence at Work (Rogers & Kelloway, 1997); Fear of Future Violent Events at Work, (Rogers & Kelloway, 1997). Proper authorization for its implementation, translation and adaptation to Portuguese was requested and granted;

- General Health Questionnaire (Golberg, 1972) with the permission of the authors, we used the version adapted to the Portuguese by McIntyre, McIntyre & Redondo (1999);

- Physical Symptoms Inventory (Spector & Jex, 1998); in 2012 we accessed information available on one of the authors’ web sites: Paul Spector, (http://shell.cas.usf.edu/~pspector/scalepage.html).

The study obtained a favourable opinion from the ethics committee of the Escola Superior de Saúde, IPV (Nº21/2012).

To apply the data collection instruments, the procedures regarding informed consent have been met with an email sent to all the inspectors in continental Portugal and the islands of Madeira and the Azores explaining the objectives of the study and with a link that would give access to the online self-assessment tools.

The expression of informed consent was on the cover page. On submitting the instruments, the data was sent into a database without the possibility of participant identification, ensuring anonymity and confidentiality.

5.1 Physical Violence at Work Scale

Thewas developed and validated by Rogers & Kelloway (1997). It consists of eight items arranged in an ordinal Likert-type scale with four classes that indicate a frequency. Respondents are asked to indicate how many times [from 0 () to 3 ()] they experienced events of physical violence (e.g., being kicked, grabbed or pushed) or its threat (e.g., threatening to damage personal property) at work during the past year. Higher scores reflect greater experience of physical violence at work. The scale’s psychometric properties were studied first by Rogers & Kelloway (1997) registering a Cronbach’s alpha of .650, and replicated in later works (e.g., LeBlanc & Kelloway, 2002; Mueller & Tschan, 2011; Schat & Kelloway 2000, 2003) with alpha values ranging between .90 values for participants outside the public sector and .63 for respondents in the public sector (Mueller & Tschan, 2011).

The psychometric study for this sample revealed reasonable Cronbach alpha values. Having calculated the reliability index by the split half method, the split-half coefficient values proved to be weaker for the first half (.358) than for the second half (.664) with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of .680 for the overall scale.

5.2 Psychological Aggression at Work Scale

The was developed and validated by Schat, Desmarais & Kelloway (2006). In its original form, it consists of three factors (three subscales) representing exposure to psychological aggression at work stemming from three sources: colleagues, supervisors and members of the public.

It is an ordinal Likert-type scale in a response format with four categories. Participants are asked to indicate how many times [from 0 (never) to 3 (4 or more times)] they have been subjected to psychological abuse (e.g., treated rudely, been the target of rude comments) at work in the last year. Higher scores reflect more psychological aggression at work.

In the validation study of the “public” subscale developed by Schat, Desmarais & Kelloway (2006) an overall Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of .87 was recorded.

In this study, only nine items were applied reflecting behaviour of psychological aggression in the workplace perpetrated by the public, granting the psychometric study very good alpha values with an overall value for the total subscale of .930. The split-half coefficient values decreased in the first and second half but still constitute good indicators of the subscale’s internal consistency.

5.3 Vicarious Violence at Work Scale

The was developed and validated by Rogers & Kelloway (1997), and its psychometric properties revealed alpha values ranging between .88 (Rogers & Kelloway, 1997) and .73 (Muller & Tschan, 2011). It is an ordinal scale, with five items in a Likert-type response format and whose classes indicate frequency, i.e. participants are asked to indicate how often [from 0 () to 3 ()] they had seen/heard of a co-worker/family member being threatened/experiencing violent events in the last year. Higher scores correspond to more vicarious violence.

The internal consistency of this sample showed overall alpha values of .736. The split-half coefficient values are also reasonable, as are .736 in the first half and .649 in the second half.

5.4 Fear of Future Events of Physical Violence at Work Scale

The (Rogers & Kelloway, 1997) consists of eight items to assess the extent to which respondents fear experiencing events of physical violence or their threat over the next year at work. The items correspond to the, with a change to the items which are placed in the subjunctive mood (e.g., I fear that during the next 12 months...). In this work, as indicated by the author, a five-class response scale was used, from 1 () to 5 () indicating the degree of agreement/disagreement. Higher scores reflect greater fear of future events of physical violence at work.

The original scale had 10 items with seven rating scales from 1() to 7(), and had good internal consistency (.94) (Schat & Kelloway, 2000, 2003, LeBlanc & Kelloway, 2002; Muller & Tschan, 2011).

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients obtained in this study reflect a good internal consistency in the eight items with an overall coefficient of .962. The split-half coefficient was also good, with .949 in the first half and .914 in the second.

5.5 Uni and multidimensional models of aggression in the workplace

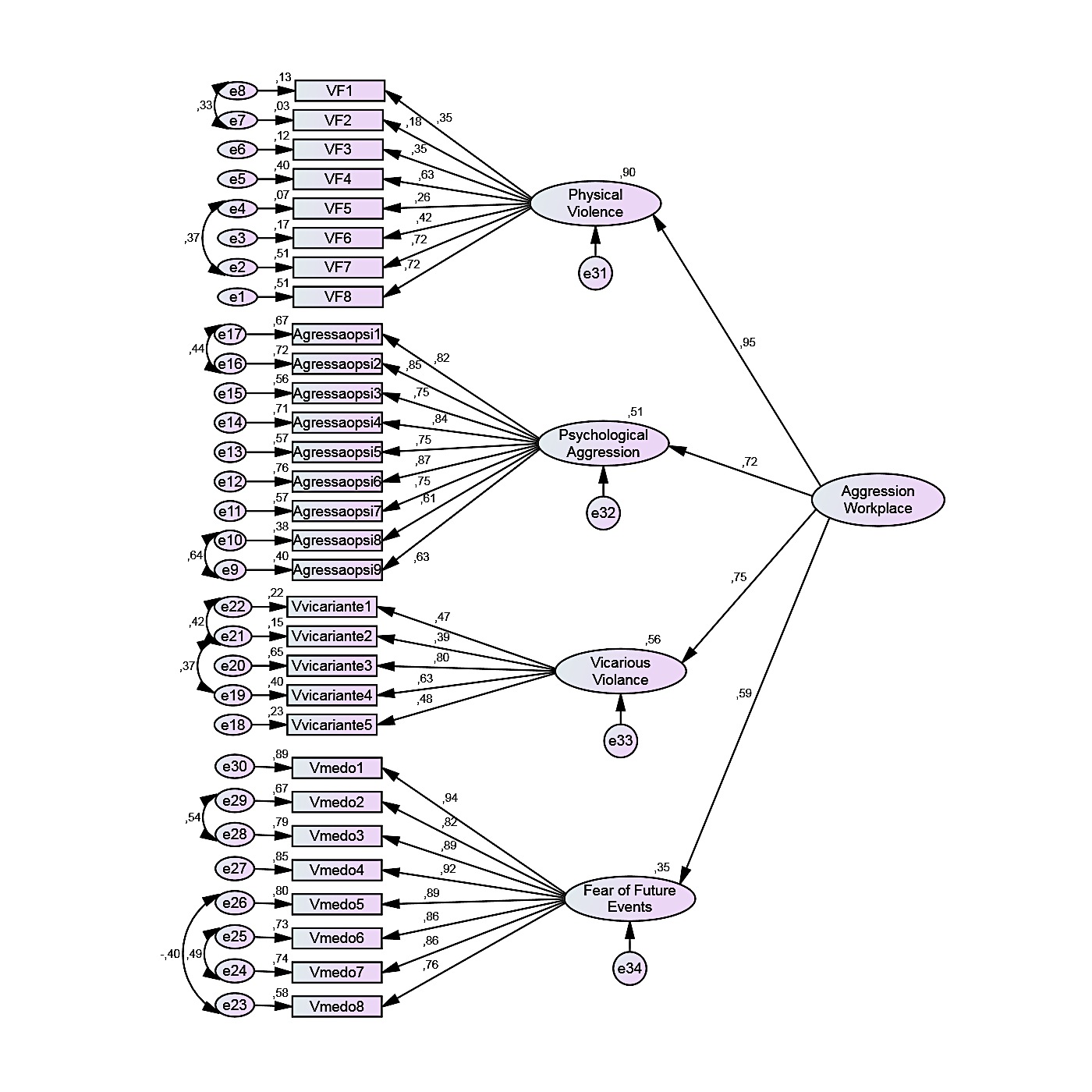

As in Schat & Kelloway (2003), given the existence of an inter-correlation between the four dimensions of aggression in the workplace, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to determine whether theandindicate aggression in the workplace as a uni or multidimensional variable. Having analysed the parameters, the comparison of the data showed a better fit when considering the aggression in the workplace in these four dimensions. The fit indices of the uni and multidimensional models without modification indices are tolerable, but after making the changes proposed, the saturated multidimensional model presents better fit indices except for GFI suggesting a tolerable fit (cf. Table1).

Second order confirmatory factor analysis showed that aggression in the workplace is a superconstruct against the four dimensions and the model is reproduced graphically in Figure1. The result was a model adjusted for χ2/g.l. (1.450), CFI (.934), RMSEA (.059), RMR (.072), SRMR (.077) indices and is tolerable for GFI (.779). Analysis of the parameters reveals that the explains 90% of the variance of aggression in the workplace, explains 56%,explains 51% andexplains 35% of aggression in the workplace.

5.6 Psychological Well-being Scale

To assess psychological well-being 12-item version of the (GHQ-12) by Golberg was applied. The GHQ is a self-assessment measuring instrument, with a first 60-item version (1972), designed to identify the respondent’s difficulty in performing their own activities in a healthy way as well as the emergence of new distress phenomena (e.g., depression, anxiety) (Goldberg & Hillier, 1979 McDowell, 2006). The items refer to symptoms or specific behaviours experienced recently. The emphasis is on changing the condition and not the absolute level of the problem. For this reason, the present psychological state (e.g., being able to concentrate on what one does) is compared to the person’s habitual situation (e.g., better than usual) (McDowell, 2006). In the abbreviated versions, half of the questions are worded with a positive orientation (e.g., has felt pleasure in daily activities) and the other half with a negative direction (e.g., has felt sad and depressed). Items can be scored by the GHQ method (0-0-1-1), the Likert method (0-1-2-3), and the Corrected GHQ or C-GHC method (0-1-1-1 for items that indicate “illness” and 0-0-1-1 for the items that indicate health) (Goldberg, Gater, Sartorius, Ustun, Piccinelli, Gureje, & Rutter, 1997). In validating the GHQ-12 coefficients, the following factors were recorded: .88 with the GHQ method, .85 with the Likert method and .86 with the C-GHC method. The effect of these different soring systems provided different cutoffs: 1/2 with the GHQ method, 11/12 with the Likert method and 4/5 with the C-GHC method. However, there are other options for the GHQ-12, including 3/4 (Goldberg, Gater, Sartorius, Ustun, Piccinelli, Gureje, & Rutter, 1997) and 4/5. Higher scores reflect worse psychological well-being.

The psychometric properties of the GHQ-12 in its adaptation for the Portuguese population studied by McIntyre (2003) in a sample that included 750 health professionals revealed a Cronbach’s alpha of .83 and a cutoff point 2/3 was used.

In this study we used the adaptation of the GHQ-12 made by McIntyre, McIntyre & Redondo (1999), opting to keep the unifactorial structure and the items were scored by the GHQ method (0-0 -1-1) with a cutoff of 2/3. The psychometric study showed good Cronbach’s alpha values for all items and global scale whose value was .844.

5.7 Physical Well-being Scale

To measure physical well-being the (PSI) Spector & Jex (1998) was used in its 12-item, 2011 version. The total score can vary between 12 and 60. The higher the score, the worse the physical well-being is. Each item is a somatic symptom and participants are asked how many times [from 1 () to 5 ()] they experienced those symptoms (e.g., headache, stomach ache) over the past 30 days. They are physical conditions/states involving discomfort or pain, as opposed to somatic symptoms that cannot be directly experienced, such as cholesterol levels or blood pressure.

Its internal consistency and evaluated its reliability were determined, as it was a first version for the Portuguese language. The psychometric study found that the Cronbach’s alpha indices are good, ranging from .805 (item 12) and .842 (item 8) to an overall alpha of .835.

Findings

6.1 Prevalence of aggression in the workplace

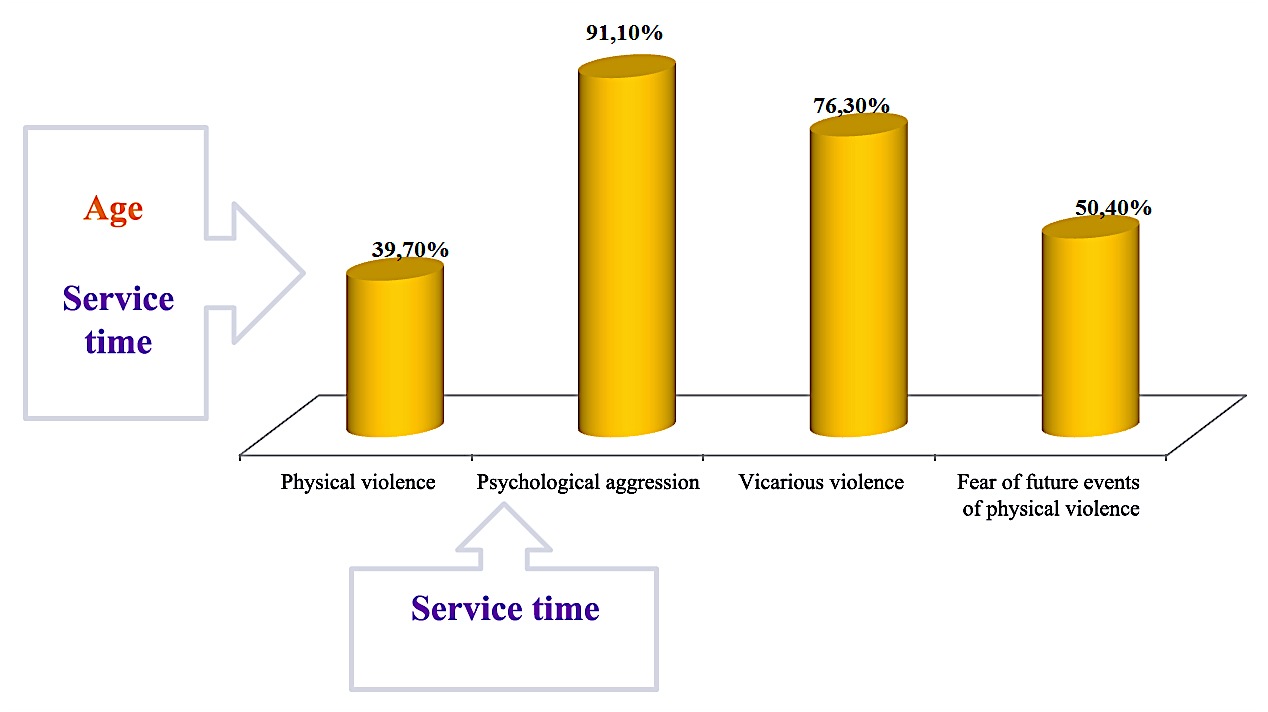

The highest prevalence was observed in psychological aggression at work (90%), followed by vicarious violence at work (76%); the lowest was recorded in physical violence (40%). It is worth noting that half of the sample say they fear future events of physical violence at work (50%) (Figure2).

6.2 Aggression in the workplace with regard to gender, age and length of service

Gender does not discriminate aggression in the workplace. However, physical violence, psychological aggression and fear of future events of physical violence at work are experienced by younger participants more, and vicarious violence at work is found in the ages between 41 and 46 years. Among the groups, we recorded differences for psychological aggression analysis of variance of one factor (3, 127)= 3.62,= .015 and fear of future events of physical violence(3, 127)= 2.86,=. 040, located between age ≤a 36 years and over 46 years, post-hoc Tukey test=.007 and=.020, respectively.

The highest rates of aggression in the workplace are among the respondents with less service time (≤5 years). The lowest rates of aggression in the workplace stood were found for service time ≥20 years. However, the differences obtained were only statistically significant for those who experienced psychological aggression, Kruskal-Wallis χ2(2,=131)= 7.88,= .019 and whose differences are between service time ≤5 years and service time ≥20 (=.038) and for those who experienced fear of future events of physical violence at work χ2(2,=131)= 8.71,= .013, with differences situated between service time ≤5 years and service time ≥20 (=.023).

6.3 Prevalence of psychological well-being with regard to gender age and length of service

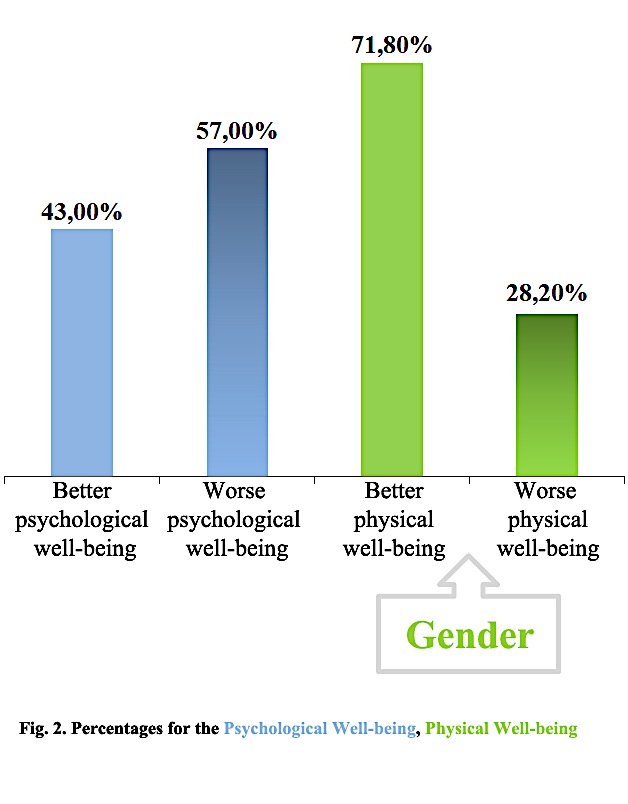

The prevalence of participants with cutoffs greater than or equal to 3, indicating worse psychological well-being was 57% and cutoffs <= 2, indicating better psychological well-being, 43% (Figure 3). The best psychological well-being occurs in men (45%) and the worst in women (58%), but the differences are not significant (χ2(1,=131)= .157,= .692). The average rates also showed that males reveal better psychological well-being than females, but without statistical significance, Levene test,(103.49)=-1.35,=.180).

The respondents aged up to 36 years showed worse psychological well-being (67%). On the other hand, the highest prevalence of psychological well-being was found in between 41 and 46 years of age, followed by those over 46 years of age, but with no statistical significance (χ2(3,=131)=1.608,=.658).

The worst psychological well-being is in those with up to 5 years of service (64%) and the best in those with a length of service between 6 and 19 years (50%), but the differences are not statistically significant χ2(2,=131)=2.252,=.324).

6.4 Prevalence of physical well-being with regard to gender age and length of service

The prevalence of participants with scores indicating physical well-being was 72%. Males (M=20.14 ±4.99 SD) have better physical well-being than females (M=22.88 ±6.45 SD) with statistically significant differences test (107.68)=-2411,=.018).

The prevalence by gender results showed that men experience less somatic symptoms (83%) and women experience them more often (66%); (χ2(1,= 131)=4.089,=.043).

In spite of registering more somatic symptoms between 37 and 40 years of age, statistical significance was not found (χ2(3, N=131)=2.080, p=.556), from which we may infer that age is not explanatory with regard to physical well-being, F (3.127)=.26, p=.849.

As for length of service, here too statistical significance was not evident (χ2(2,=131)=.526,=.769). Nevertheless, those who most often experience somatic symptoms are those with shorter service time with a percentage of 31%.

Despite the participants with service time ≤5 years and ≥20 years having mean values for worse physical well-being, the differences are not significant, Kruskall-Wallis χ2 (2,=131)=1.72,=.422.

6.5 Mediation models: Effects of physical violence, psychological aggression and vicarious violence at work on physical and psychological well-being through fear

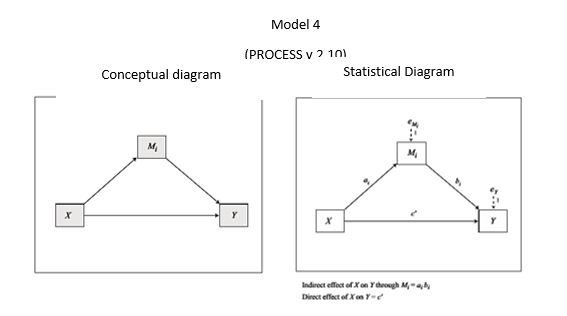

The statistical methods used to assess the model in this study, which predicted that physical violence, psychological aggression and vicarious violence at work (independent variables - X) transmit their effects on physical health and psychological well-being (dependent variables - Y) through fear of future events of physical violence at work (mediating variable - M), were simple mediation tests based on the Hayes approach (2013) and using the PROCESS.

The models available in the PROCESS only admit one independent and one dependent variable. Although the analysis for a set of independent variables is one of its limitations, we can do it by following the procedures described by Hayes (Hayes, 2013; Hayes & Preacher, 2014) .Thus, we performed six tests of the same simple mediation model whose conceptual and statistical diagrams are reproduced in Model 4 in Figure 4. In this way, we also avoid the possibility of multiple independent variables strongly correlated among each voiding each of the other effects of the mediation model (Hayes, 2013).

As implemented in the PROCESS, all mediation models were based on the covariance matrix (cf. Table 2); the regression coefficients were estimated using the OLS (ordinary least squares) regression and the overall, direct and indirect effects are presented in the non-standardised form. The final models are saturated models (cf. degrees of freedom – Table 3), so the fit is perfect (Hanssen, Vancleef, Vlaeyen, Hayes, Schouten, & Peters, 2014). The results showed that the effects of aggression in the workplace on well-being are indirect and mediated by fear. Those who experience both physical and vicarious violence feel more fear, and fear affects their physical and psychological well-being.

Conclusion

Aggression in the workplace is recognized by international organizations (e.g. ILO, WHO, NIOSH, EU-OSHA) and by researchers as an important occupational health hazard due to the negative consequences and high costs associated with it.

Measuring instruments widely used in previous investigations were adapted to the Portuguese language. The results of confirmatory factor analysis for aggression in the workplace showed the multidimensional nature of this super construct, with physical violence explaining 90% of the variance, psychological aggression 51%, vicarious violence 56% and the fear of future events of physical violence 35%, from which we may infer the psychometric quality of the measure to determine aggression in the workplace.

As for the aggression in the workplace, the highest percentage rates were found in psychological aggression at work (90%), followed by vicarious violence at work (76%), fear of future events of physical violence at work (50%) and physical violence at work (40%). It was also found that the experiencing aggression at work is independent of gender, and that age and length of service are statistically significant variables. The research by Schat, Frone & Kelloway (2006) showed that 96% of American workers who have experienced physical violence had also experienced psychological aggression. Of those who did not suffer psychological aggression, only 0.4% reported having experienced physical violence.

The percentage rates for psychological well-being showed that participants recently perceived changes in their health in general (57%) and, with regard to physical well-being 28%, reported having experienced somatic symptoms in the last month. It was also found that gender is a significant variable in relation to the physical well-being.

From an organizational perspective, this study brings information with a potential to contribute to defining prevention strategies, worker protection and reducing the adverse effects of aggression in the workplace, particularly on the relevance of evaluative monitoring of the phenomenon which should include the subjective experience of behaviours of physical violence, psychological aggression, vicarious violence and fear of future events of physical violence at work and their effects on individuals.

Replicating this research in longitudinal studies, with other samples, with other outcome variables, and new mediation and moderation variables will enrich the theoretical framework of aggression in the workplace with practical implications for individuals and organizations.

The results convey information which supports conceptualization and assessment models of workplace aggression as a nosologic entity originating in negative physical and psychological experiences lived by individuals in their workplace.

Knowledge and a better understanding of the types and dimensions of the phenomenon of violence and aggression in the workplace is a powerful support instrument for defining more effective prevention strategies. Autonomy and job satisfaction are resources associated with reduced levels of fear of future events of violence perpetrated by customers and its recognition may represent a fruitful approach with practical implications.

Acknowledgements

FCT, CIEC, Universidad of Minho, Portugal // CI&DETS, Health School, Polytechnic Institute of Viseu

References

Arnold, K. A., Dupré, K. E., Hershcovis, M. S., & Turner, N. (2011). Interpersonal targets and types of workplace aggression as a function of perpetrator sex. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 23(3), 163-170. Acedido em

https://umanitoba.ca/faculties/management/media/Nick_Turner_PDF8.pdf

Barling, J. (1996). The prediction, experience, and consequences of workplace violence. Violence on the job: Identifying risks and developing solutions, 29, 49. Acedido em

http://web.business.queensu.ca/faculty/jbarling/Chapters/The%20Prediction,%20Experience%20and%20Consequences%20of%20Workplace%20Violence.pdf

Barling, J., Dupré, K. E., & Kelloway, E. K. (2009). Predicting workplace aggression and violence. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 671-692. Acedido em

http://web.business.queensu.ca/faculty/jbarling/Chapters/Predicting%20Workplace%20Aggression%20and%20Violence%202.pdf

Baron, R. A., & Neuman, J. H. (1996). Workplace violence and workplace aggression: Evidence on their relative frequency and potential causes.Aggressive behavior, 22(3), 161-173. Acedido em

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(1996)22:3<161::AID-AB1>3.0.CO;2-Q/abstract

Dionisi, A. M., Barling, J., & Dupré, K. E. (2012). Revisiting the comparative outcomes of workplace aggression and sexual harassment. Journal of occupational health psychology, 17(4), 398. Acedido em

http://web.business.queensu.ca/faculty/jbarling/Articles/2012%20Dionisi%20Barling%20Dupre.pdf

Dupré, K. E., & Barling, J. (2003). Workplace aggression. Misbehavior and dysfunctional attitudes in organizations, 13-32. Acedido em

http://web.business.queensu.ca/faculty/jbarling/Chapters/Workplace%20violence%20duprer.pdf

European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound). (2015). Violence and harassment in European workplaces: Extent, impacts and policies, Dublin. Acedido em

http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_comparative_analytical_report/field_ef_documents/ef1473en.pdf

European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound) e European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). (2014). Psychosocial risks in Europe: Prevalence and strategies for prevention, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. Acedido em

http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_publication/field_ef_document/ef1443en_0.pdf

Goldberg, D. P., Gater, R., Sartorius, N., Ustun, T. B., Piccinelli, M., Gureje, O., & Rutter, C. (1997). The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychological medicine, 27(01), 191-197. Acedido em

http://mbh.hku.hk/icourse/documents/backup/MSBH7002%20-%20Goldberg%201997.pdf

Hanssen, M. M., Vancleef, L. M. G., Vlaeyen, J. W. S., Hayes, A. F., Schouten, E. G. W., & Peters, M. L. (2014). Optimism, Motivational Coping and Well-being: Evidence Supporting the Importance of Flexible Goal Adjustment. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1-13. Acedido em

http://link.springer.com/article/

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press

Hayes, A. F., & Preacher, K. J. (2014). Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 67(3), 451-470. Acedido em

http://www.quantpsy.org/pubs/hayes_preacher_2014.pdf

Hershcovis, M. S., & Barling, J. (2007). 16 Towards a relational model of workplace aggression. Research companion to the dysfunctional workplace: Management challenges and symptoms, 268. Acedido em

http://www.untag-smd.ac.id/files/Perpustakaan_Digital_2/ORGANIZATION%20BEHAVIOR%20Research%20companion%20to%20the%20dysfunctional%20workplace,%20management%20challenges%20an.pdf#page=284

Hershcovis, M. S., Turner, N., Barling, J., Arnold, K. A., Dupré, K. E., Inness, M.,& Sivanathan, N. (2007). Predicting workplace aggression: a meta-analysis. Journal of applied Psychology, 92(1), 228. Acedido em

https://umanitoba.ca/faculties/management/faculty_staff/media/Hershcovis_et_al_JAP_2007_metaanalysis.pdf

Hershcovis, M. S., & Barling, J. (2010). Towards a multi‐foci approach to workplace aggression: A meta‐analytic review of outcomes from different perpetrators. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(1), 24-44. Acedido em

https://umanitoba.ca/faculties/management/faculty_staff/media/Hershcovis_and_Barling_2010_JOB.pdf

Hershcovis, M. S. (2011). “Incivility, social undermining, bullying… oh my!”: A call to reconcile constructs within workplace aggression research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(3), 499-519. Acedido em

http://www.sc.edu/ombuds/doc/Herschcovis_2011.pdf

LeBlanc, M. M., & Kelloway, E. K. (2002). Predictors and outcomes of workplace violence and aggression. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(3), 444. Acedido em http://nreilly.asp.radford.edu/leblanc%20and%20kelloway.pdf

LeBlanc, M. M., & Barling, J. (2004). Workplace aggression. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(1), 9-12. Acedido em https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Julian_Barling/publication/258127905_Workplace_Aggression/links/54ca97320cf2c70ce5227796.pdf

McDowell, I. (2006). Measuring health: a guide to rating scales and questionnaires. Oxford University Press. Acedido em

http://a4ebm.org/sites/default/files/Measuring%20Health.pdf

McIntyre, T., McIntyre, S., Araujo-Soares, V., Figueiredo, M., Johnston, D. & Faria, F. (2003). Psychophysiological and psychosocial indicators of the efficacy of a stress management program for health professionals: Final report Bolsa Fundação Bial nº 41/98. Maia: Fundação Bial.

Mueller, S., & Tschan, F. (2011). Consequences of client-initiated workplace violence: The role of fear and perceived prevention. Journal of occupational health psychology, 16(2), 217. Acedido em

http://www2.unine.ch/repository/default/content/users/setschan/files/papers/Mueller%20%26%20Tschan%20(2011).pdf

Neuman, J. H., & Baron, R. A. (1998). Workplace violence and workplace aggression: Evidence concerning specific forms, potential causes, and preferred targets. Journal of management, 24(3), 391-419. Acedido em

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Joel_Neuman/publication/254121227_Workplace_Violence_and_Workplace_Aggression_Evidence_Concerning_Specific_Forms_Potential_Causes_and_Preferred_Targets/links/54b877760cf28faced621301.pdf

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate behavioral research, 42(1), 185-227. Acedido em

https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/bitstream/handle/1808/1658/preacher_rucker_hayes_2007.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Rogers, K. A., & Kelloway, E. K. (1997). Violence at work: personal and organizational outcomes. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 2(1), 63. Acedido em

http://workplaceviolence.ca/sites/default/files/Rogers%20%26%20Kelloway%20(1997)--Violence%20at%20work-Personal....pdf

Schat, A. C., & Kelloway, E. K. (2000). Effects of perceived control on the outcomes of workplace aggression and violence. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(3), 386. Acedido em …

Schat, A. C., & Kelloway, E. K. (2003). Reducing the adverse consequences of workplace aggression and violence: The buffering effects of organizational support. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology; Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 8(2), 110. Acedido em

http://faculty.buffalostate.edu/hennesda/reducing%20workplace%20aggression.pdf

Schat, A. C., & Kelloway, E. K. (2005). Workplace Aggression. In J. Barling, E.K. Kelloway, & M. Frone (Eds.), Handbook of Work Stress (pp. 189-218). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Schat, A. C. H., Desmarais, S., & Kelloway, E. K. (2006). Exposure to workplace aggression from multiple sources: Validation of a measure and test of a model. Unpublished manuscript, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada. Acedido em http://scholar.google.pt/scholar?hl=pt-PT&q=exposure+to+workplace+aggression+from+multiple+sources&lr=

Schat, A. C., & Frone, M. R. (2011). Exposure to psychological aggression at work and job performance: The mediating role of job attitudes and personal health. Work & Stress, 25(1), 23-40. Acedido em

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3105890/pdf/nihms278682.pdf

Spector, P. E., & Jex, S. M. (1998). Development of four self-report measures of job stressors and strain: Interpersonal Conflict at Work Scale, Organizational Constraints Scale, Quantitative Workload Inventory, and Physical Symptoms Inventory. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology; Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 3(4), 356. Acedido em

http://www.psychwiki.com/dms/other/labgroup/Measufsdfsdbger345resWeek1/Lindsay/Spector1998.pdf

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 July 2016

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-012-9

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

13

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-462

Subjects

Health psychology, psychology, health systems, health services, ocial issues, teenager, children's health, teenager health

Cite this article as:

Pacheco, E., Cunha, M., & Duarte, J. (2016). Violence, Aggression and Fear in the Workplace. In S. Cruz (Ed.), Health & Health Psychology - icH&Hpsy 2016, vol 13. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 27-41). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.07.02.3